'Becoming Frida Kahlo' on PBS is a perceptive, intimate look at the iconic artist

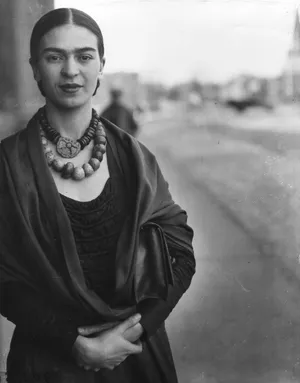

Do an online search for Frida Kahlo products and you’ll find a marketplace of Frida robes, Frida mugs, Frida tote bags, Frida socks, Frida hairspray and an array of Frida T-shirts bearing her signature look: the deep-red lips, the bold eyebrows, the fearless gaze, the regal tiara of fresh flowers in her hair.

Why exactly is a rule-breaking revolutionary figure who died nearly 70 years ago still so popular? And why, as a new three-part documentary on PBS asks, do we still keep looking at her?

“Becoming Frida Kahlo,” which airs its remaining episodes Sept. 26 and Oct. 3 (check local listings), is a perceptive and remarkably intimate look at the Mexican artist whose life speaks to a multitude of issues that confront us today, everything from discrimination aimed at women, people of color and the LGBTQ community to income inequality, women’s health care gaps and the lack of support for those with disabilities.

Kahlo was many things: vibrant, irreverent, brilliant, politically radical, purposefully controversial. "Art was her superpower," says one of the documentary's interviewees. Young people, particularly young women, relate to her desire to be treated with respect, not for conforming to the old norms but for being true to herself.

“She speaks to the younger generation in a way that few historic figures do, I think, particularly few artists — almost no other artists,” says Mark Hedgecoe, an executive producer of “Becoming Frida Kahlo.”

The documentary was produced by Rogan Productions Scotland for the BBC. Its director, Louise Lockwood, an award-winning filmmaker and fine arts graduate of the Glasgow School of Arts, says she jumped at the chance to do the project when it was offered.

“As soon as somebody said the word 'Frida,' I said: ‘Yes! Yes, yes, yes, yes, yes,’” says Lockwood, who spent six weeks with her team in the United States and Mexico to film significant locales in Kahlo’s world.

Relying on photos and Kahlo’s paintings, readings from her writings and those of her friends, and interviews with family members, biographers and academics, the documentary delves into the many traumas that she overcame as well as her triumphs in an era when women weren’t taken seriously, either as artists or cultural figures.

Born in 1907 (she later claimed it was 1910, to tie it to the start of the Mexican Revolution), Kahlo faced serious health problems at a young age. A childhood bout of polio resulted in one of her legs being shorter than the other. A horrific bus accident left her at age 19 with multiple broken bones and internal injuries from a metal rail that pierced through her body.

“In this hospital, death is dancing around my bed at night,” she wrote, as the documentary reveals. Yet she recovered and went on to thrive in the cosmopolitan climate of Mexico City, embracing radical politics and mingling with the counterculture of her age.

During her long recuperation, she took up painting. That led to her meeting celebrated Mexican artist Diego Rivera, whom she loved obsessively and would marry, divorce and remarry. Their turbulent relationship — marked by his many affairs, including one with her sister Cristina, which devastated her, and her affairs with women and men, including Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky — is at the heart of her story, but it never stopped her from creating art that was psychologically complex and visually arresting.

One of the most gripping parts of the documentary covers Rivera and Kahlo’s time in Detroit, where they lived in the early 1930s while he painted the famous "Detroit Industry" murals, a gift from Edsel B. Ford to the Detroit Institute of Arts. Lonely and homesick, Kahlo described the city as “a shabby old village” while allowing that the industrial areas were the most interesting. In one self-portrait, she painted a scene in Mexico to her right and belching Ford smokestacks to her left that obscure an American flag.

Kahlo became pregnant in Detroit, nearly dying about four months after an agonizing miscarriage. She put what happened into an extremely personal 1932 painting “Henry Ford Hospital,” which depicts her as bleeding on a bed with the hospital’s name inscribed on its side. As she reclines there, umbilical-like cords connect her body to several floating objects, including pelvic bones and a fetus.

Her miscarriage was followed by the news that her mother was gravely ill in Mexico City. Kahlo rushed home, where her mother died after an operation. The two losses left a deep imprint on Kahlo, whose art dealt graphically with the extremes of love and tragedy.

In fact, one of her greatest works, 1939’s “The Two Fridas,” which was finished soon after she and Rivera divorced, has side-by-side images of two Kahlos. They're dressed differently, with their hearts exposed and connected by an artery that bleeds onto the white dress of the Frida on the left. In the documentary, someone interprets it as her way of telling Rivera, “You have torn me apart.”

Only about 3½ minutes of Kahlo exist on film, and that was one of the obstacles Lockwood faced in making her series. “You can’t really put it on a loop, can you?” she says. “But the bits that did exist were brilliant and kind of set the tone.”

What she did have was a multitude of photos and self-portraits that help make Kahlo a vivid presence, along with the readings from her letters.

Lockwood worked with a predominantly female team that also had key members from Mexico, like cinematographer Alex Roa. Lockwood says the team's goal was always to get inside Kahlo’s point of view. When they would shoot at sites associated with her, like La Casa Azul (the Blue House), her birthplace and longtime home that’s now the site of the Museo Frida Kahlo, the camera would act as Kahlo’s eyes. ”I’d be filming in a place thinking about where she’d be looking. That was my task and challenge, and I quite loved it.”

Whenever the documentary’s team was in doubt about something, according to Lockwood, it turned to Kahlo herself for answers. ““When it got complicated, (we asked,): ‘What is Frida thinking, what is she feeling, where is she looking?’ We always brought it back to her rather than, ‘What has Henry Ford done?'”

Kahlo created her persona through her distinctive style, which she cemented through her self-portraits, and controlled her image in front of the camera lens, too. She was rarely caught off guard by photographers taking her picture. Like contemporary superstars, she manifested her destiny through her work and her vision. Says Lockwood, “Despite everything that happened to her, to use a really modern term, she had agency.”

Before her death at 47 in 1954, Kahlo had physically declined and become bedridden. Weary of living, she wrote, “I await the exit with joy, and I hope never to return.”

In a sense, Kahlo didn’t get her way. Her fame has soared, her art has increased in acclaim and value, and her fans have become legion. More successful now than she was during her lifetime, Frida's legacy is everywhere. In terms of her influence, she never really left.

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.