'The Blues Brothers' came out in June 1980. Is there a better Chicago movie? Not for me

The following is adapted from “The Blues Brothers: An Epic Friendship, the Rise of Improv, and the Making of an American Film Classic,” published March 19 by Atlantic Monthly Press. The author isDaniel de Visé, a personal finance reporter for USA TODAY.

One summer evening, back in the ‘80s, I filed into a Chicago theater and beheld my city on the big screen, pretty much for the first time.

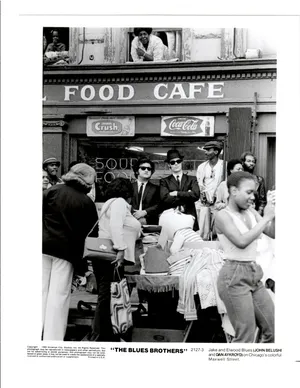

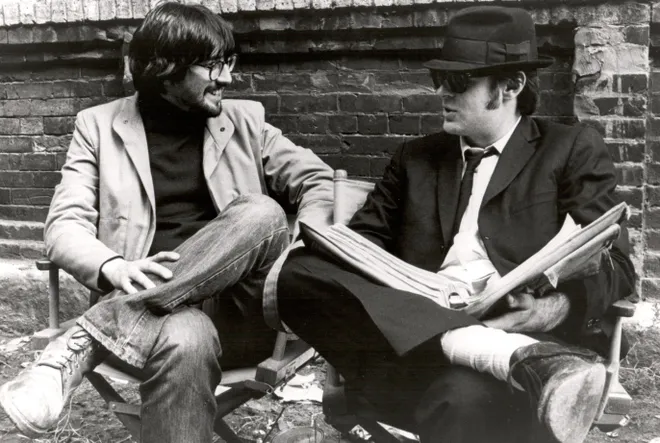

I saw "The Blues Brothers," the crazy car-crash comedy musical, starring John Belushi and Dan Aykroyd and directed by John Landis.

The film came out on June 20, 1980. I was 12, and it was rated R, so I didn’t see it until a couple of years later, at the Parkway Theatre on Clark Street, where movies cost a buck or two and no one asked your age.

From that night, "The Blues Brothers" was my Chicago film.

Check out: USA TODAY's weekly Best-selling Booklist

Critics panned it at the time. Today, "The Blues Brothers" ranks at or near the top of the list of great Chicago films. For many Chicagoans of a certain age, "Blues Brothers" is foundational. It means enough to me that I wrote a book about it.

Join our Watch Party!Sign up to receive USA TODAY's movie and TV recommendations right in your inbox

Is there a better Chicago film than 'The Blues Brothers'?

Is there a better Chicago film? The Brothers’ biggest competition is probably "Ferris Bueller’s Day Off," the great John Hughes comedy, released six years later.

Here, let’s pause for a brief geography lesson.

I am from the city: born on the South Side, raised mostly on the North.

John Hughes was from the suburbs: Northbrook, to be exact.

(Random fact: My father and I used to drive out to Northbrook on Thursdays in summer to watch bicycle races. My father emigrated from Belgium and raced bicycles with other low-country immigrants in his youth. But that’s another story.)

Hughes set several of his films in the Chicago suburbs, and especially in the North Shore, the necklace of suburban jewels that flank Lake Michigan, north of the city: Places like Winnetka, where the "Home Alone" house just went up for sale, priced at a cool $5.25 million.

North Shore kids used to flock into the city on weekends, generally making a beeline for downtown, or the Miracle Mile, or Wrigley Field.

In that sense, "Ferris Bueller" was a picture-perfect portrayal of a rich suburbanite’s relationship with the city.

It was a great Chicago film, but it was not my Chicago film.

Chicago is 'like 'The Blues Brothers' if you're poor'

“Chicago is like ‘Ferris Bueller’s Day Off’ if you’re rich,” one local musician recently observed in Jacobin magazine, “and it’s like ‘The Blues Brothers’ if you’re poor.”

I would define the dichotomy more in terms of city and suburb, but you get the idea.

Ironically, Belushi was himself a suburbanite, born in the city but raised mostly in Wheaton, a place so remote it barely qualified as a suburb.

But Belushi escaped to Chicago at his first opportunity. And the Blues Brothers, the fictional ones, were very much of the city.

When Elwood retrieves Jake from Joliet Prison at the start of the film, their eventual destination is a flophouse apartment in the Loop, a downtown space defined by L tracks.

“How often does the train go by?” Jake asks.

“So often you won’t even notice it,” Elwood replies.

Much of the film was shot in the suburbs, but not the John Hughes suburbs. Noooo: We’re talking Harvey, a struggling south-suburban hamlet with enough crime problems to shutter a mall at the height of the mall era. And Wauconda, a sleepy outpost farther from the city than Wheaton.

Jake and Elwood seem to spend most of the film trying to get back to the city. Not since "The Warriors," released a year earlier, had anyone fought so hard, and against such long odds, to get home.

'106 miles to Chicago'... from where, exactly?

It was never entirely clear where the Brothers are supposed to be when they set out on their final push, and Elwood announces, “It’s 106 miles to Chicago.”

In the film’s fanciful plot, the band plays a climactic gig at a fictional Palace Hotel Ballroom, on a fictional Lake Wazzapamani.

The production yielded few clues to its location: The crew shot the exteriors at the South Shore Cultural Center, an old Mediterranean revival structure on Chicago’s South Side. They filmed the interiors at the Hollywood Palladium, the art deco palace on Sunset Boulevard.

Thankfully, much of the film plays out in the city, paying glorious, gritty tribute to Daley Plaza, the downtown government campus; Maxwell Street, the famed open-air market; Lower Wacker Drive, the base of a double-decker roadway that threads through downtown; Bronzeville, the South Side neighborhood that housed the fictional Ray’s Music Exchange; and Chez Paul, the real River North restaurant where North Shore kids and their parents gathered to dine.

And here is another reason why "The Blues Brothers" matters so much to Chicago: When the film hit theaters, 44 years ago this month, it gave many Chicagoans their first real look at their city on a movie screen.

More:What the 'mission from God' really was for 'The Blues Brothers' movie

A film drought on Lake Michigan

In the years of my childhood, precious few films shot in Chicago, a prohibition that dated to the early years of Mayor Richard J. Daley. A powerful Irish American politician from the Southwest Side, Daley banished film and television crews from his city in 1959, when an episode of a now-forgotten series called "M Squad" portrayed a Chicago cop taking bribes.

If you grew up in New York or San Francisco or Philadelphia or Los Angeles, you could see your city on screen all the time, in such priceless cinematic artifacts as "Saturday Night Fever," "Dirty Harry," "Rocky" and "Chinatown."

A few film crews talked their way into Chicago: Remember "Cooley High"? But not many.

Yet, by 1979, when "The Blues Brothers" came to town, Mayor Daley was dead. Jane Byrne had just taken office as Chicago’s first female mayor. She was happy to let the production in.

The late mayor’s cronies had lined up against Byrne, calling her a “crazy broad” and worse.

When Byrne met with cast and crew, Belushi asked if his friends could drive a car right through the lobby of the Richard J. Daley Center.

“I wouldn’t have a problem with that,” Byrne replied.

And so, Mayor Byrne and "The Blues Brothers" threw open the gates to Chicago as a setting for a new generation of classic films.

"The Breakfast Club" (1985) and "Home Alone" (1990) are suburban Chicago. "The Untouchables" (1987) is old-time Chicago. "The Fugitive" (1993) is action-movie Chicago. "High Fidelity" (2000) is hipster Chicago.

And ‘The Blues Brothers’ is my Chicago.

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.