Lower-income workers face a big challenge for retirement. What's keeping them from saving

Having enough cash to cover the bills must be job one when it comes to retirement savings.

Yet, the retirement gap − the risk of not having enough money throughout retirement to cover typical spending − is widest among late baby boomers in their early to mid-60s, who have low-paid to middle-income jobs, according to new retirement readiness research.

The challenge? This group − who likely could be living paycheck to paycheck now − typically will need nearly as much money to cover their bills in retirement as they do while they're working and collecting a paycheck. But their Social Security checks and other savings might only enable this group of lower-paid workers to cover less than two-thirds of their pre-retirement spending, according to Fiona Greig, global head of investor research and policy at Vanguard.

Many fear financial shortfalls in retirement

Millions of people face substantial shortfalls when it comes to living comfortably, not lavishly in retirement. We're not talking about booking Viking cruises or hauling five or six grandkids to Walt Disney World here.

It's easy to think your experience will be the same as someone else's when it comes to saving for retirement but it's not the case. The availability of traditional pensions has changed a great deal in the past 15 years or more. And people who haven't seen steady pay raises find a greater portion of their paychecks going to cover everyday expenses.

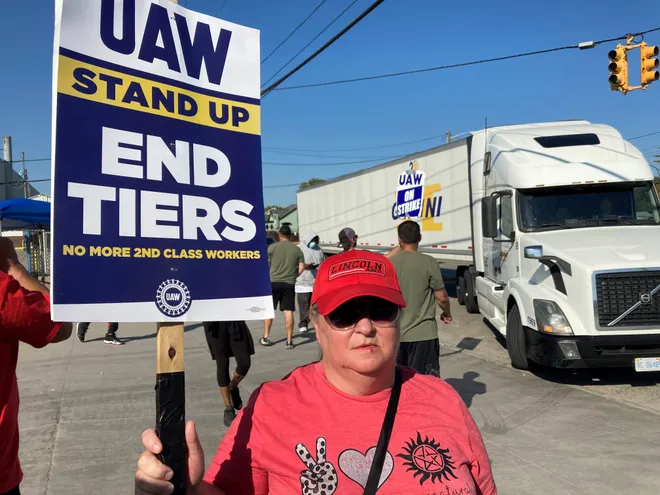

One point that came to light during the contentious United Auto Workers strike against the Detroit Three was how financially vulnerable many autoworkers feel today, given that those hired in the fall of 2007 and afterward no longer have a traditional pension.

I talked with some workers in their 50s who had $50,000 or less saved for retirement − and had no pension to back them up.

The tentative agreements at Ford Motor Co., Stellantis and General Motors all address some of the angst and savings shortfall by boosting the employer contributions to 401(k) plans of those hourly workers not covered by the traditional pension.

All three of the tentative agreements include a 10% contribution from the employer on up to 40 hours of pay each week into the 401(k) plan. That's up from a 6.4% contribution of base wages by the Detroit Three for those hired in the past 16 years or later. There is no required contribution into the 401(k) from these hourly workers to get this money.

How much income do you need to replace in retirement?

How much money you'd need in retirement often reflects what you're earning now. Often, people are given a general number saying they need to replace between 70% and 85% of their income. While it's not a bad assumption, it's not the same for everyone.

Some groups now need to replace nearly all of their annual income each year in retirement.

"For low-income families, they need to replace a higher fraction of their income than that benchmark figure," Greig said.

"Based on spending patterns in retirement," she said, "we estimate that families in that income level need to replace 96% of their preretirement income."

"There's little in their budget to cut."

Low-income workers are defined as those who earn roughly $22,000 in the year before retirement. They make less money than 75% of the overall population Their incomes are so low that they don't have many frills to cut back on. Much of their money goes toward necessities.

For this group, Greig said, Social Security will replace 62% of their pre-retirement income. It's a sizable amount of money, and a bigger replacement figure than for higher-income workers, but we're still looking at a sizable savings gap.

Nearly 34% − or 34 cents for each dollar of spending − needs to be replaced somehow to cover the bills, such as through employer-sponsored retirement savings plans, and individual savings. In some cases, one option could even end up being selling the family home and moving to a lower-cost area, if the family has built up home equity it can liquidate by selling.

Many times, the Vanguard research indicated, low-income families only can save so much and may be able to tap into their savings to contribute an estimated 2% of what's needed to cover bills in retirement − leaving a 32% gap.

Retirement systems rated:How does the U.S. retirement system stack up against other countries? Just above average.

Retirement savings protection:Biden wants to protect your retirement savings from junk fees? Will it work?

Many underestimate how long they'll live in retirement

Many people put their retirement at risk by underestimating how long they'd need their savings to last in retirement. Underestimating potential longevity can lead you to think you're better prepared for retirement than you might be, making you more willing to save less money or take a chance at retiring early in your late 50s.

And there is financial fatigue − dreading the notion that your 401(k) savings could be slashed in half by the next bear market on Wall Street. Many times, people aren't able to tap into a pension, even a small one so they depend a great deal on their own savings.

"We don't know exactly how long people live," Greig said, "and we don't know exactly what kind of stock market return environment people will experience."

More people than you might imagine don't have anything saved for retirement.

Some 28% of non-retired adults do not have any retirement savings, according to the Federal Reserve's 2022 Survey of Household Economics and Decision-making. That's up from 25% in a 2021 survey.

Younger adults, those ages 18-29, tended to have less retirement savings, along with Black, Hispanic, and disabled non-retirees, according to the Fed.

Some higher-income workers see a small 'retirement gap'

How much people will need to spend in retirement, relative to what they made when they were working, typically will vary significantly by income. For most groups, the Vanguard report noted, projected income in retirement does fall short of spending needs but the gap isn't as big as it is for lower-income workers.

"The goal post for what people should be targeting as a replacement rate really depends on what their income level is," Greig said.

Higher-income workers, for example, need to replace a smaller percentage of their pre-retirement income in retirement.

Those with a median income of $61,000 − making more than 70% of the overall population − can be expected to turn to Social Security to replace 40% of their income. Because they have more discretionary spending as they're working, they'd need 68% of their pre-retirement income to cover expenses in retirement.

Even after tapping into their savings, the Vanguard report noted, they're still looking at a 17% savings gap.

By contrast, higher-income workers − those making roughly $173,000 a year − spend only 43% of their pre-retirement income in retirement, according to the Vanguard study. This group has far more in savings and can cover 63% of their pre-retirement income. Social Security only replaces 18% of the pre-retirement income for this group.

For many workers, the solution can be to delay retirement and keep working if able. If they've built up equity in the home, they might be able to sell it, invest the money and then rent. But that's a strategy few take.

Some public policy issues need to be addressed, as well.

Greig said the data gives more reason to "shore up what we already have," noting that Social Security is critical to the financial well-being of many people as they age.

Some innovation will be key, such as plan sponsors engaging in getting more nonparticipants into 401(k) plans and conducting “under-saver sweeps” that make sure employees are saving enough to maximize the employer match for their contributions, according to Vanguard.

Beginning in 2025, federal law will require companies with new 401(k) plans and 403(b) plans to automatically enroll eligible employees at a minimum employee contribution rate of 3%, but no more than 10%. The employee may opt-out if they do not want to set aside that much of their paychecks.

To be sure, employers won't be required to offer 401(k) plans under Secure 2.0. Roughly half of all workers in the United States don't have access to an employer-sponsored plan. So, Greig said, expanding access is important.

Retirement isn't a one-size-fits-all kind of deal, much like everything else in our financial lives. Not all groups see surges in wealth from an inheritance or feel secure after years of tucking away extra cash in a 401(k).

Contact personal finance columnist Susan Tompor: stompor@freepress.com. Follow her on Twitter @tompor.

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.