A widow opened herself up to new love. Instead, she was catfished for a million dollars.

Liza Likins, who sang backup for such music icons as Stevie Nicks and Linda Ronstadt, was lonely and depressed after her husband, Greg, died in 2020.

When a handsome blond-haired man who resembled her late husband of 23 years started messaging her on Facebook, Likins rebuked him for four months.

But eventually, Likins was lured into a relationship with "Donald," who worked mining gold in Australia.

"I fell in love with this person; deeply, deeply in love. It was almost 2 ½ years of this going on," said Likins.

Or so she thought.

Instead, Likins gave more than $1 million to a romance scammer – someone who convinced the singer he was in love with her, and he would join her in Las Vegas.

"Now I know that he is a criminal. I know he's a major criminal who preys on lonely, widowed women," she said.

In 2023, consumers lost $1.14 billion to romance scams, which bilk people out of money for love, according to new information released Friday by the Federal Trade Commission. There have been a total of 64,003 cases reported in 2023. Both numbers are down from 2022 and 2021, but “are still very high compared to other types of scams, reflecting that it continues to be a significant issue,” the FTC said.

Likins, who used up all of her savings and sold her house for “Donald” and the fake dream, said she was at times suicidal after she found out the truth. But she now wants to prevent other women from falling prey to such schemes and has enlisted a company that’s helped her track down the scammers who are based in Nigeria. She hopes to “flip the script,” and have them arrested.

"It is definitely an embarrassing and humiliating experience to be deceived," she said.

And Raho Bornhorst, a German man whose images were used by scammers to bilk Likins and hundreds of other women, says he is also a victim. He’s on a mission, too, working with Meta to take down the dozens of fake profiles using his photos – and to implement stricter standards so others don’t get duped.

“It’s really terrible because I hear and feel and see their tears,” Bornhorst said. “They’re writing to me because they think they’re in love with me for one or two years already and then they discover it’s just me, the real one.”

What is a Romance scam?

Romance scams are big business.

◾ In 2023, romance scams ranked second only to investment scams in total reported dollar losses.

◾ As in 2021 and 2022, social media was the top romance scam contact method in 2023, ranked by both total reported losses and by number of reports.

◾ Also as in 2021 and 2022, cryptocurrency was the top romance scam payment method ranked by total reported losses.

Who is Liza Likins?

Likins, 75, who goes by the stage name Liza Jane, made her first album in 1968. She sang backup vocals for many musicians, including Ronstadt and Stevie Nicks. Nicks was maid-of-honor at Likins’ first marriage to Kenny Edwards of the Stone Poneys.

Likins also went on tour with Fleetwood Mac and was Nicks’ roommate for 10 years.

Her second marriage was to Greg Likins, who helped manage her singing career and finances. In 1968, he had been her first boyfriend and played lead guitar on her album.

Greg fell ill in 2020, around the time of the COVID-19 shutdown. It took some time to find out what was wrong, but he was diagnosed with metastatic melanoma and died six weeks later.

After Greg’s death, Liza said she went into a deep depression and isolated herself in her Vegas home. But after about seven months, friends told her she needed to meet some people.

She changed her marital status on her Facebook account to widowed and soon started getting messages from men. One reminded her of Greg. She ignored him.

“Then at the end of four months, he sent me a picture of him meditating with Buddha. That got me. I went, OK, this is a good guy,” Likins recalls.

The two began talking multiple times a day. She began falling in love with the man who was showering her with attention.

What happened to Liza Likins?

The first time Donald asked for money, it was for $1,000 to get him some Wi-Fi time to call her from the gold mines in a rural part of Outback Country in Australia, where he worked. Their communications were mostly via the What’s App platform, which offers free international texting and phone calls.

Eventually, the tale got bigger. Donald was preparing to come to Vegas to marry Liza and he was sending his retirement money. He showed a videotape of him putting money and gold bars equaling $700 million in a red safe that was going to be shipped to Liza. He would be there three days later.

“And that’s when all the big money and Bitcoin money started changing hands,” she said.

He needed $140,000 for a logistics company. Liza researched the company, and it was real. But then things snowballed and the stories began to sound like a James Bond movie.

The lies included the package getting stopped by authorities, someone offering to get plastic surgery to look like Donald to accept the package and eventually Donald himself getting arrested and thrown in a Spanish prison.

He would need $250,000 to get out on bail. Liza sold her house to get the bail money.

“There were pictures that went with every story,” she said. “His story was bulletproof.

“I went to the airport four times to pick him up. I’ve still never met him.”

Likins was convinced the man she knew as Donald was coming to live with her – even after she saw a show about other women who had been conned out of their money by a supposed suitor. She reached out to the company that produced that episode.

The company, Social Catfish, which verifies online identities using reverse search technology, has been working with Likins and tracked the cryptocurrency she used to scammers in Nigeria. Likins used the information to file reports with the FBI but has not heard back. Social Catfish, which featured Likins in an episode of its YouTube show, “Catfished: Presented by Social Catfish,” has been working with authorities in Nigeria to close in on Likins’ predators.

How did Likins not know she was being catfished?

The scammers preyed on Likins’ loneliness, she said. They studied her Facebook posts to know what appealed to her: “Buddhism, spirituality and my belief in God,” Likins said. “They played on all of those things.”

“Donald” found real photos of Bornhorst with a Buddha behind him and other photos to go with the narrative, she said.

There were also altered pictures.

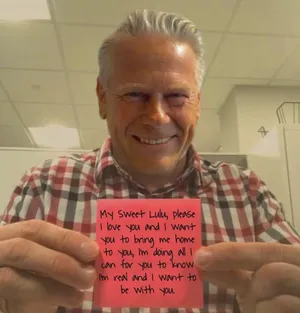

Liza received a photo supposedly of Donald in a Spanish prison, needing bail money, holding a sticky note professing his love for her and desire to join her.

At one point, Likins said she almost thought she knew Donald from a different life, or that he was her late husband in another form. Donald even called Likins some pet names her late husband had called her. She thinks scammers found them by studying her Facebook posts.

Likins said at times their phone calls would cut out or Donald would say he couldn’t send a text or video because of the patchy service. The one time she asked for a video call, it was fuzzy and she couldn’t make out anyone’s face.

“This Donald guy had somebody else pretend it was him and rig the video and then they just press play every time they’re supposed to talk to you so that their mouth is moving...so you think it’s real,” she said.

“It’s all phony baloney. It’s all lies.”

Unraveling the mystery

Romance scammers are specifically targeting emotionally vulnerable people, said Social Catfish Founder David McClellan.

And all scammers, not just those engaged in romance schemes, prey on people’s psychology, he said.

“Scammers use similar tactics to scam victims where they fall in love with you and they separate you from your family and they make you make decisions very quickly so that you don’t have time to think about it,” McClellan said. “They do small little things for you to make you feel like you owe them.”

In a lot of cases the victims are lonely, depressed, or in a situation that opens them up to believe the lies, he said.

Once the victim “goes down the rabbit hole,” sometimes they have a hunch something is wrong, but then they are in so deep that they try to see it through to get their money back, McClellan said.

It’s not just women who are victimized, McClellan said. About 50% of the clients who come to the Social Catfish website are male, he said. Men are more reluctant to report their scams since they tend to be more of a sexual nature and they’re embarrassed, McClellan said.

McClellan started his company more than eight years ago to help protect people online. The company has developed software and sells subscriptions. The Catfished Channel features 52 episodes a year where McClellan and his team help a scam victim who hasn’t had luck with law enforcement, doing the groundwork to track down as much information as they can for the victim to hand over to authorities. McClellan’s team also works with law enforcement in other countries, such as Nigeria, to try to nab the scammers.

Scams are 'gray area' for law enforcement

Romance scams and similar schemes where someone pretends to be someone else and steals money are often a “gray area” for local or national law enforcement because while the victims have been tricked, they still willingly gave away their money, McClellan said.

Likins says she has contacted the FBI three times with her story. She has never heard back. An email from USA TODAY to the FBI for comment on Likins’ case was not returned. The FBI often does not confirm or deny an investigation.

McClellan said Nigerian authorities have found at least one person involved in the scam that targeted Linkins, but he doesn’t know additional details since the inquiry is ongoing.

McClellan has tried to lower Likins’ expectations because even if the scammers are caught, he said, it is likely they bilked many victims, and the money is gone.

The real man in the pictures speaks out

Raho Bornhorst is a life coach and success mentor for entrepreneurs in Germany. Part of his job is public speaking and sharing about his life on Facebook and other social media sites.

But in a video interview with USA TODAY, Bornhorst said that doesn’t mean scammers have the right to take his photos and use them to dupe other people.

Bornhorst has been in contact with Likins through Social Catfish, whose employees verified his identity. Likins said Bornhorst, in his real-life capacity as a life coach, has been very comforting and helpful, and she’s had to remind herself that she is not in love with him, but rather a persona scammers created, using his photos.

For three years, Bornhorst has been contacted by at least 100 women who thought they were in love with him and said that he scammed them out of their money.

Bornhorst, who is single and does date, but not online, knows how vulnerable the women feel. Four years ago, he was bilked out of roughly $150,000 by a woman he too met online.

Getting action to wipe out fake profiles

Bornhorst blames Meta, the owner of Facebook for allowing fake profiles to remain on the site. He and his friends have constantly reported fake profiles, some of which have been up for years, to the social media company. None had been taken down and Bornhorst said he’d been told they didn't violate Facebook standards.

A search of Facebook found at least 13 accounts with Bornhorst’s name and image. He said only two are his – one personal and one professional.

“Of course, I allow my picture to be shown on Facebook, but I do not allow somebody else copying my photo and pretending to be me. That’s definitely not legal,” he said.

USA TODAY contacted Facebook/Meta on behalf of Bornhorst and Bornhorst shared his real personal and professional profile pages. The next day Meta sent this statement:

“Scams are unfortunately used to deceive, defraud, and manipulate people across the internet. People who impersonate others on Facebook and Instagram violate our policies, and we remove this content when it’s found – like in this case. Our work in this area is never done, and we continue to invest in detection technology and work with law enforcement to prosecute scammers.”

Don't get scammed:Make these 5 New Year's resolutions to avoid scams this year

Meta also shared that it “removes large numbers of impersonating accounts on a consistent basis through a combination of technology, reporting tools and human review.” Meta said its detection technology helps block millions of attempts to create fake accounts every day and detects millions more within minutes of creation. In its last Community Standards Enforcement Report, Meta said it removed 827 million fake accounts on Facebook, 99% of which were before they were reported as fake.

After Meta removed some fake Bornhorst profiles, his real Instagram account was inadvertently removed. Bornhorst also reported another 10 fake profiles using his images but another name. Meta fixed those issues.

A Meta spokesperson said there were no further updates to the statement when asked why fake profiles Bornhorst had been reporting for the last three years had not been removed before the company was contacted by USA TODAY.

Confronting 'Donald'

After Likins learned the truth about “Donald” from Social Catfish, she confronted him. Donald told her not to throw away what they’d worked so hard to build and they’d soon be together.

Likins was still hopeful that might be true, even though Social Catfish told her it wasn’t. She sent Donald $6,000 for a private jet to bring him to Las Vegas. When he was supposed to have arrived, he said he was being detained by Homeland Security. Likins went to the security office and they knew nothing about him.

The last time Likins spoke to Donald was around Christmas 2022. He told her he’d pay her back triple what she’d sent – totaled to be more than $1.2 million by Social Catfish.

By then, Likins was in production for the Catfished show and knew the truth. She changed her phone number, as well as her Facebook profile and blocked Donald.

Picking up the pieces

Likins said the scammers have destroyed her and left her with no money. She’s had her electricity turned off twice. She has struggled to buy food and gas for her car. She has lost friends who mocked her for getting scammed.

In the midst of all of this, Likins also had to have surgery on her spinal column and her vocal cords have suffered. She can’t sing the way she used to, she said. She’s working on a book about her music life and also a book about being scammed.

Likins is hopeful her scammers will be prosecuted, but she’s given up hope that she’ll get any money back.

She encourages women to date in person. Likins is now dating, but only men she can physically see in the same room.

“As soon as somebody asks for money, block them and don’t ever talk to them again,” she said. “If I had done that, I’d still have a nice, cozy comfortable life.”

Tips to avoid falling for a Romance Scam

Here are tips from the FTC and McClellan, the Social Catfish CEO:

◾ Scammers pretend to be heroes in faraway places. The phony Marines, soldiers, admirals, generals, diplomats, and surgeons claim they can’t speak or show their faces because they’re in Afghanistan, Ukraine, or South Sudan – but they aren’t.

◾ Scammers say they’re in love. You can’t meet these faraway “friends” in person, but they’ll chat with you daily. Too soon, they surprise you with declarations of love, or ask to marry you, and say you can share all your secrets (and money) with them now. Don’t believe them.

◾ Scammers ask for expensive favors. They might ask you to accept a package of cash, gems, and gold and pay the fake “shipping fee” that really goes into their pocket. Or, they ask for new phones to replace broken ones or beg for gift cards and presents for the “kids they left back home.” (There aren’t any kids.) If you say OK to one request, they come back with another – and then another.

◾ Scammers always ask for money. They make plans to visit but tell you they’re delayed by costly problems: a lost airline ticket or visa, a medical emergency, or a blocked account. They say if you could send them some money, they could still come see you. But the minute your online love interest asks for money, you know it’s a scam. Want to know who else is a scammer? Anyone who asks you to share account numbers, send gift cards or wire transfers, or pay them with payment apps or cryptocurrency.

◾ If you think someone is a scammer, cut off contact. Tell the online app or social media platform right away, and then tell the FTC at ReportFraud.ftc.gov. Also report them to local law enforcement, the FBI, or the FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center.

◾ And remember, people of all ages can be scammed. McClellan has seen victims as young as 18.

Betty Lin-Fisher is a consumer reporter for USA TODAY. Reach her at blinfisher@USATODAY.com or follow her on X, Facebook, or Instagram @blinfisher. Sign up for our free The Daily Money newsletter, which will include consumer news on Fridays, here.

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.