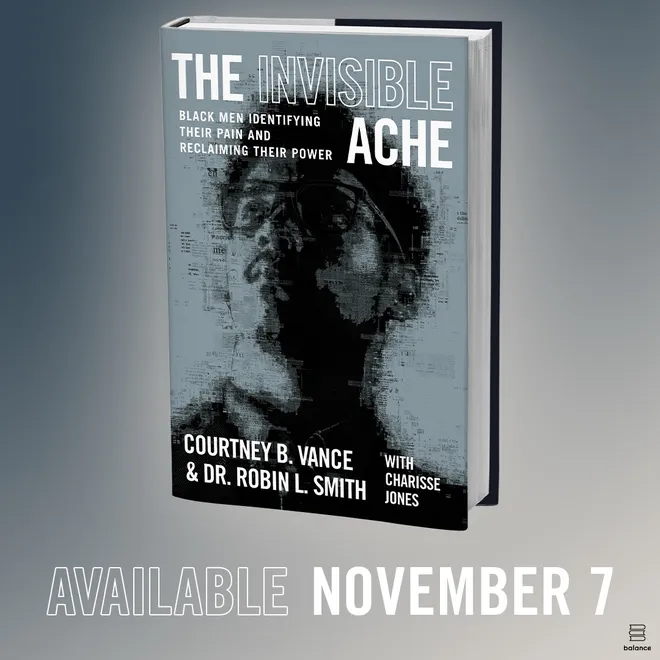

Courtney B. Vance shares impact of family suicides in 'The Invisible Ache': Read an excerpt

A global pandemic. A racial reckoning. Conversations about politics that too often devolved or erupted. In the past few years I saw so many people who were anxious, so many in despair. It seemed the whole world was teetering, with people’s nerves as taut as a trip wire.

I also realized that mental distress was difficult for many to talk about, shrouded in stigma, hidden in shame. And for Black men, living under the specters of racism and marginalization, vulnerability and mental fragility could be even harder to acknowledge.

So when I was given the opportunity to co-write a book on Black men and mental health with the esteemed actor Courtney B. Vance and psychologist Dr. Robin L. Smith, I saw it as an opportunity to not just pull back the curtain but to tear it down, shattering myths, creating community and helping men and boys find a path toward healing.

The candor of Vance, whose father and godson died from suicide, coupled with Smith’s professional guidance will be particularly instructive to Black men who may be struggling. But I am certain that "The Invisible Ache" can help anyone grappling with grief, wading through anxiety, living with depression. In other words, "The Invisible Ache: Black Men Identifying Their Pain and Reclaiming Their Power" (Balance, 288 pp.) will hopefully be a blueprint that benefits us all. Below, is an excerpt from the book, available now.

Read an excerpt from 'The Invisible Ache' about Courtney B. Vance's family, life

Sometimes those around you can do everything right. They ask you where does it hurt? They ask how can they help? They draw you close. They raise you up. And still, it isn’t enough.

I met Bobby Robinson through mutual friends more than a decade ago. We hit it off, stayed in touch, and grew to be close friends. So close that he and his wife, Patricia, asked Angela and me to be godparents to their children.

Angela and I were in our forties when we had our babies, and we were always looking for role models, folks we felt were parenting successfully. Bobby and Patricia were two we admired from afar.

We spent hours and hours together, and the Robinson kids became like an older brother and sister to our son, Slater, and our daughter, Bronwyn. Angela and I loved our godchildren fiercely. But no matter how close you are to someone, you don’t know everything that’s going on in their home. Nor should you. People have a right to decide what they want to share, and if and when they want to share it. So I didn’t learn until much later that my godson began to struggle emotionally when he went off to college.

To everyone looking in, he was a smart, handsome kid who was also a great drummer, but he was spiraling. Finally, his parents decided to bring him home. That seemed to be what he needed, to be with those who loved him most, to be in a safe place where he could get his bearings.

Then COVID 19 hit. The pandemic created a new challenge for so many young people, stripping away school, preventing them from socializing with their friends. They were isolated, and perhaps encountering death and serious illness for the first time. It also meant that if your child wasn’t well, they might have to interact with a doctor by themselves as social distancing protocols prevented their loved ones from accompanying them into a medical office or hospital.

That’s what happened with my godson. Twice, after he experienced a mental health episode, Bobby and Patricia took him to the hospital— but they had to wait outside in their car while he went in alone.

One day in 2020, on a date I don’t want to remember, he hung himself in his room.

Having lived through my father’s suicide didn’t make my godson’s death any less devastating. In some ways, it may have been even more traumatic, because the family had tried so hard to save him, and because he was so young with so much promise and possibility hovering on the horizon.

He was the Robinsons’ baby boy, their older child, their only son. He was his sister’s and Slater’s and Bronwyn’s big brother. For twenty-three years, the Robinsons had been a quartet, their lives filled with this beloved young man’s rhythm, and now he was gone.

For those whose loved one takes their own life, the ostracization, the questions, just add to their devastation. That may make even some of those who survive want to take themselves out the same way.

Thirty years earlier, my father had killed himself. Now, my twenty- three-year-old godson had done the same thing. Two people I’d loved more than anyone in this world had taken their own lives. I thought, I can’t do this again. I can’t do this anymore. I’ve got to speak up. I’ve got to say something. We were losing too many people who couldn’t find the hope to hang on.

There are so many young men like my godson, who seem to have everything to live for but can’t get through a terribly bleak moment, who feel they can’t bear to be in this life for one minute more. One suicide would be too many, but now it feels like an epidemic is coursing through the Black community like another plague and pandemic.

I knew I needed to let my brothers, those who are young like my godson, and those in their senior years like my father was, know that it was okay to need therapy or medication to help them make it through. I needed to talk to them about how there were boys and men like themselves who were taking their own lives, and there was help out there, so they didn’t have to take the same devastating and permanent step.

I knew we had to bring mental anguish and illness out of the shadows, to stop yelling “You crazy,” like it’s an insult. Because we all struggle, we all spiral, we all have moments when we are confused. So, by that definition, we’re all crazy. The insults needed to stop. And the understanding needed to begin.

Excerpted from The Invisible Ache by Courtney B. Vance and Robin L. Smith with Charisse Jones. Copyright © 2023 by Courtney B. Vance and Robin L. Smith with Charisse Jones. Reprinted with permission of Balance Publishing, an imprint of Hachette Book Group. All rights reserved.

Charisse Jones is an economic opportunity reporter with USA Today

If you or someone you know needs support for mental health, suicidal thoughts or substance abuse call, text or chat:

988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline: 988 and 988lifeline.org

BlackLine: 800-604-5841 and callblackline.com

Trans Lifeline: 877-565-8860 and translifeline.org

Veterans Crisis Line: Dial 800-273-8255 and press 1 to talk to someone or send a text message to 838255 to connect with a VA responder. You can also start a confidential online chat session at Veterans Crisis Chat. veteranscrisisline.net

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.