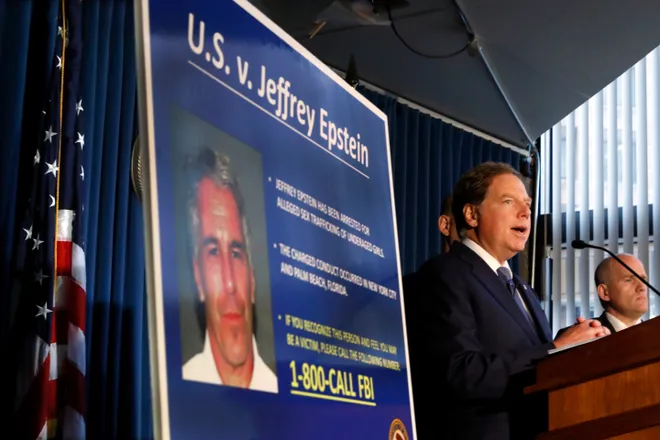

The 'Epstein list' and why we need to talk about consent with our kids

With the Epstein list in the news, important conversations are being had about sexual violence, power and the law. But something big is still missing. We are not talking about consent.

Many adults, adolescents and children are gravely misinformed about what consent is, how it is given, when it is valid and when it's invalid. The consequences are grave and life altering.

As someone who has experienced sexual violence, as a mother and as an attorney who works on issues of sexual violence and the law, I am constantly reminded of the ways we fail on this incredibly important issue.

Sexual violence isn't determined by the victim's response

I didn't understand consent the first time I was sexually abused. That's because I was in middle school. On my way to my first boy-girl party, my father had an awkward and rushed discussion with me about how girls got pregnant and why I was too young to have sex.

But no one ever talked to me about consent. After the assault happened, I figured that since I didn't kick and scream, since I didn't claw my abuser's face off, it was my fault. I carried that thought with me for years, secretly. It had repercussions in my life that I spent decades remedying.

It wasn't until my first-year criminal law class that I fully understood what had happened to me, and that I didn't consent all those years ago and why I behaved the way I did after the fact.

By then, the statute of limitations in Colorado barred me from bringing legal action against my abuser and the woman who facilitated it.

To protect victims' rights and to ensure that criminals don't evade justice, a recent international case should serve as a compass for U.S. lawmakers. In Angulo Losada v. Bolivia, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights issued a ruling last year that makes explicitly clear where human rights law stands on the issue of consent, drawing on jurisprudence from other international courts.

In the case, Brisa de Angulo Losada, then 16, was sexually assaulted and raped by her cousin who was 10 years older. Her aggressor argued that it was consensual. After three trials in Bolivia, the case ended up in the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. The court detailed that in a relationship where there is an asymmetrical power relationship, there can never be voluntary consent, regardless of whether the person is over the age of consent or if they didn't fight back.

It also reiterated that a person can withdraw consent at any time, that consent has to be clearly and affirmatively communicated and that consent should be the centerpiece of any rape law rather than proving physical violence or mental incapacity.

It's time to ban 'crime-free laws':For domestic violence survivors, calling for help can be deadly. Or cost them their home.

Rape laws fail to adequately protect survivors

Rape laws in the United States generally aren't based on consent and fail to protect victims nearly enough. For example, in Alabama, sexual violence laws are based on forced compulsion or the inability to give consent (being unconscious, for instance).

In my home state of Colorado, consent does not have to be freely given and affirmative (unambiguous, conscious, informed, voluntary and mutually agreed upon). That leaves a gray area that helps no one except the perpetrators of sexual violence.

Most states have statutes of limitations defining when victims can bring civil actions alleging sexual violence. These laws demonstrate an outdated, misogynistic mentality about rape.

Ashley Judd:We have the power to help women and girls caught in crises. Why won't we?

We know that most perpetrators of sexual violence have a close relationship to the victim, which makes it more difficult, more confusing and more terrifying to physically fight back.

When a teacher, cousin, parent, financial benefactor, significant other or spouse is the rapist, most victims freeze − immobilized by the horror of what is happening to them. After, there could come threats of consequences if the victim says anything, and feelings of shame and guilt that can quiet even the most outraged into silence. We also know that it can take victims years to come forward because of that same shame, fear and guilt.

I am a mother now, and I am doing my best to make sure my kids have the building blocks to understand consent. We all should be.

My daughters are still very young, but I have taught them to loudly say "No!" to anyone who touches them in a way, or in a place, that feels bad.

I have taught them that their teacher, coach, family member or friend has no right to touch their body, or make them touch theirs. I have taught them that they will never get in trouble with me for telling me if something scary or bad happened – that they have to tell me the truth so I can make sure they are OK, or get help if they aren't.

In a few years, I will make sure they understand consent and how most often it's people close to us who take advantage of that relationship to violate our rights.

We do a disservice to our youth by avoiding in-depth conversations about this critical piece of sexual health and protection from violence.

We also do a great disservice in allowing statutes of limitations to block childhood victims of sexual violence from seeking their day in court, and by continuing to have laws on the books that base rape and sexual assault on proving physical violence or mental incapacity.

No one wins with laws like these. No one wins when we don't talk about consent.

Carli Pierson is a digital editor at USA TODAY and an attorney. She recently finished a legal consultancy with Equality Now, an international feminist organization working to eliminate sexual violence and discrimination against women and girls.

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.