'One of the best summers': MLB players recall sizzle, not scandal, from McGwire-Sosa chase

George Springer was a week shy of his ninth birthday when his dad bounced downstairs in their Connecticut home and, although it was a school night, rousted him from slumber and urged him to come upstairs.

“You’ve got to see this.”

Moments earlier, Mark McGwire hit his 62nd home run, breaking Roger Maris’s single-season record with his rival and burgeoning bosom buddy, Sammy Sosa, standing in right field. The game stopped. A kid groundskeeper found the ball. As the summer of ’98 was fading into fall, its most compelling drama reached its zenith.

Sleep could wait.

“You just thought 61 or 62 homers was the most unobtainable thing you’ve ever heard of in your life,” says Springer, the four-time All-Star, World Series champion and now center fielder for the Toronto Blue Jays. “When you look back at it, it’s two really good baseball players having a great season and not just providing their respective teams, but their whole sport with a lift. It was a crazy time.

FOLLOW THE MONEY: MLB player salaries and payrolls for every major league team

“There’s an argument to say that’s one of the best summers of baseball anybody has ever watched. Because you were so locked into what those guys were doing.”

Twenty-five years later, the summer of Big Mac and Slammin’ Sammy feels, in many respects, so much different. By 2001, three years after breaking the unbreakable record, McGwire ceded his home run crown to Barry Bonds, who thumped 73 home runs to top McGwire’s record of 70.

By 2005, McGwire and Sosa were called before a congressional committee exploring steroid use in baseball and offered testimony ranging from dodgy to nebulous. In 2010, McGwire admitted to steroid and human growth hormone use before beginning his career as a major league coach.

EXCLUSIVE:25 years later, Mark McGwire still gets emotional reliving 1998 Home Run Chase

McGwire, who hit 583 home runs, and Sosa, who slugged 609, were both roundly rejected by Hall of Fame voters.

Yet for current major leaguers, who have only known rigorous and regular testing for PEDs in their baseball careers, the Summer of Swat is hardly sullied.

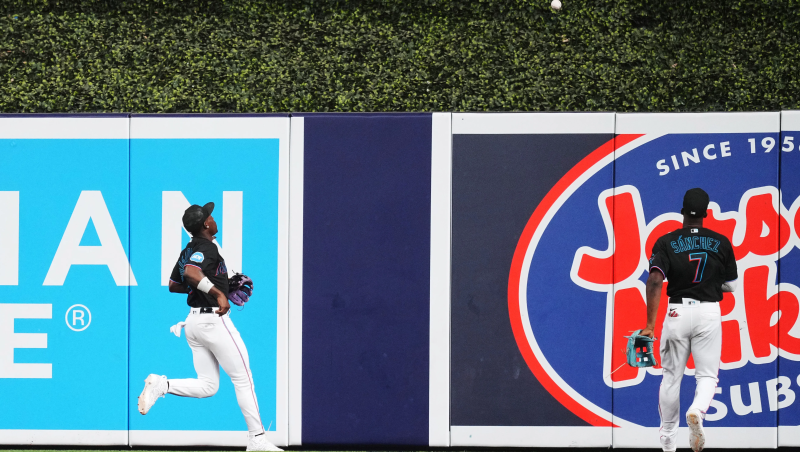

“Looking back on it now, I know there’s some controversy behind it but I don’t really view it any differently,” says Miami Marlins veteran catcher Jacob Stallings, “because for me as a kid, it was so exciting to watch.

“That’s how I remember it and I’ll leave the rest of it to people who want to worry about it.”

Indeed, for all the forthcoming scandals, the talk of asterisks and the roughly decadelong reckoning with PEDs that baseball endured, it is challenging for the millennial generation to simply cast aside their most significant socialization into baseball simply because less-flattering facts emerged.

That summer, multiple major leaguers said, will always have a where-where-you element to it, no matter the age.

Evan Longoria was 12 years old, a Southern California kid who felt connected to the chase because WGN, the superstation that broadcast almost every Cubs game, was everywhere.

And so were McGwire and Sosa − leading SportsCenter every morning, one's home run total queued up whenever the other came up to bat.

"I just remember thinking that baseball was at the top of its popularity. It was everywhere," says Longoria, 37, a three-time All-Star now with the Arizona Diamondbacks.

"They made it cool to be a baseball player."

For Stallings, it was, appropriately enough, almost exactly halfway between St. Louis and Chicago.

His father, the college basketball coach Kevin Stallings, was the head coach at Illinois State at the time and the family lived in Bloomington, southwest of Chicago. It was Cubs country, but the elder Stallings grew up a Cardinals fan, so Big Mac was young Jacob’s guy.

Washington Nationals first baseman Dominic Smith, now in his seventh major league season, turned 3 years old that summer. Yet even a kid that young can tell something’s a big deal just by watching others.

“You don’t remember too much,” he says, “but I remember the excitement of my family – my uncles, my dad and seeing them react to seeing something that amazing.

“It seemed like they almost hit a home run every night. One hit one, the next one hit two. It really brought an energy and buzz back to the game of baseball, which had left for a bit.”

The popular narrative then was that McGwire and Sosa “saved baseball” as the sport was flagging just three years after a lengthy players’ strike and lockout canceled the 1994 World Series and stretched into the ’95 season. (How soon we forget: Cal Ripken Jr. had already “saved baseball” by breaking Lou Gehrig’s all-time consecutive games record in September 1995, but we digress).

“I don’t know if I grasped all that as a kid,” says Stallings, 33, who said he was more into basketball at that point of his childhood. “I just know there was a lot of excitement.”

Seven seasons after that record-breaking year, MLB and the MLB Players’ Association began the first drug-testing policy with penalties – which began as a paltry 15-game suspension, but now has been strengthened to 80 games for first-time offenders.

Testing in the minor leagues had already begun, and when this generation of players came up, it was simply part of their reality.

“Guys want it as fair and as clean as you possibly can. That’s why the drug testing is as hard core as it is, the amount of times and the randomness of it,” says Springer. “Guys can say what they want about that race. I was just an 8-year-old kid watching guys hit homers. But now, you just want the game to be as clean as it can.”

PED testing has also returned context to the home run, which, even as more players swing for the fences at the expense of their batting average and strikeout totals, has not reached the single-season McGwire-Sosa-Bonds stratosphere.

THE ADMISSION:Teammates, coaches admire Mark McGwire despite steroid admission

The odd juiced-ball year – such as 2019 or 2017, when Giancarlo Stanton hit 59 home runs – can inflate totals across the board. But hitting anywhere near 70 without the fear of repercussions over PED use has not happened.

That’s why Aaron Judge’s run to 62 home runs – now the American League record – last year resonated so strongly, even without the everyday fervor.

“I think we were all watching Judge last year and rooting for him,” says Stallings. “It was kind of a McGwire-Sosa race of our era, watching him go after it. It was cool to see him do it.”

And in his generation’s eyes, the McGwire-Sosa remains pretty cool, too. After all, they were simply a product of their era.

“You can’t discredit what they did. Because I’m sure whatever they were taking, 80, 90% of the league was taking it too,” says Smith. “They were just a little bit better.”

Contributing: Bob Nightengale

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.