Mel Tucker changed his story, misled investigator in Michigan State sexual harassment case

On a sunny Thursday morning, Michigan State University football coach Mel Tucker strolled through tomato fields at a farm in Immokalee, Florida, toured its processing plants and loaded baskets of bright green fruit into a truck.

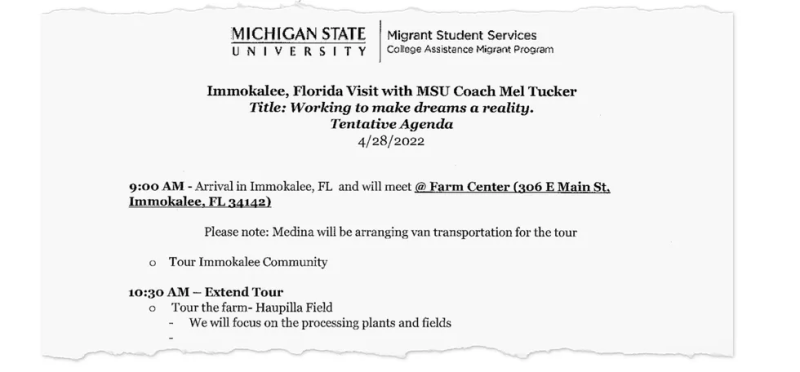

It was a private event thrown by the school to promote its migrant student services program, which provides financial aid and support to farmworkers seeking college degrees. After the April 28, 2022, tour, disclosed in records obtained by USA TODAY this week, Tucker met with community leaders and alumni.

That night, Tucker would make the now-infamous phone call from his hotel room in nearby Naples, during which he is accused of masturbating and making unwanted sexual comments to Brenda Tracy, a prominent rape survivor and activist he had hired to speak to his team about sexual violence.

Yet, when Tucker met with the university’s outside investigator in March for his interview in the sexual harassment case against him, he insisted the trip was not work-related – a claim the investigator would disprove in her report.

It’s just one example of Tucker failing to keep his story straight at the most consequential moment of his career.

With his job, reputation and the roughly $80 million left on his contract at stake, Tucker repeatedly made false statements to the investigator and misled her about basic facts, such as his location during the phone call and the date it occurred, a USA TODAY review of more than 1,200 pages of case documents found.

The investigator, Rebecca Leitman Veidlinger, and the news organization both obtained documents and witness statements that discredit key aspects of Tucker’s version of events.

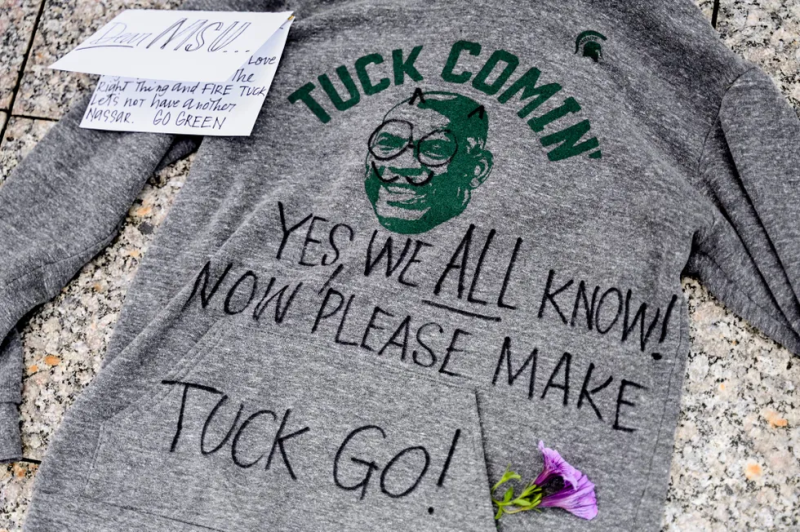

Michigan State suspended Tucker without pay on Sept. 10, hours after Tracy went public for the first time with her story in USA TODAY. On Monday, the school informed Tucker it plans to fire him for cause based on the conduct he had admitted to and the embarrassment he had caused the school.

Investigation:Michigan State football coach Mel Tucker accused of sexually harassing rape survivor

Although Tucker denied sexually harassing Tracy, he acknowledged masturbating on the call, saying he and Tracy had been in a romantic relationship and had consensual “phone sex.” Tracy said Tucker’s romantic interest in her was completely one-sided and that she had tried to set boundaries multiple times during their yearlong business partnership.

Per his contract, Tucker has until Sept. 26 to make a case for keeping his job. Regardless, a formal hearing to determine whether Tucker violated school policies against sexual harassment and exploitation is expected to proceed on Oct. 5 and 6.

Since his suspension, Tucker has issued multiple public statements defending himself, attacking Tracy and accusing Veidlinger of bias. He accused the school of conducting a “sham” hearing and having “ulterior motives.” Yet even in these written statements, central details of his story changed entirely.

Tucker, who previously hung up on a reporter who called him on his cellphone asking about the case, did not respond to a message seeking comment for this story. His attorney, Jennifer Belveal, has not responded to phone calls and emails. Tracy declined to comment for this story.

In the absence of eyewitnesses or recordings, sexual harassment cases usually boil down to whose account is more credible, said Elizabeth Abdnour, a Lansing-based attorney and former Michigan State Title IX investigator who has taken part in dozens of campus cases.

“It’s very, very unusual that you would have some outside piece of evidence that would give you a clear decision,” Abdnour said. “Very often you’re weighing credibility based on little bits and pieces of information.”

In multiple cases she has worked, Abdnour said the respondents lost because they were found to have a greater propensity for lying than the complainants. The hearing officer must determine how much weight to give Tucker’s false and conflicting statements, Abdnour said, and they could sway the case in Tracy’s favor.

“I believe a fact finder could assess these pieces of evidence about credibility and make a determination that Brenda is more credible than Mel,” she said. “In my experience, a clear sign of a lack of credibility is generally taken very seriously.”

Misleading statements about where and when the call happened

By the time Tucker met with Veidlinger for his interview, he had had months to prepare.

The school had informed him of Tracy’s complaint on Dec. 22, the day after she filed it. Veidlinger had interviewed Tracy and all six of her witnesses by the end of January. Tucker was the only holdout.

Rather than tell his side of the story right away, Tucker and his attorney spent three months trying to stop the investigation, case documents show. They wrote legal arguments urging Michigan State to drop the case and twice approached Tracy’s attorney proposing a settlement agreement. Tracy said no, and the school pressed forward.

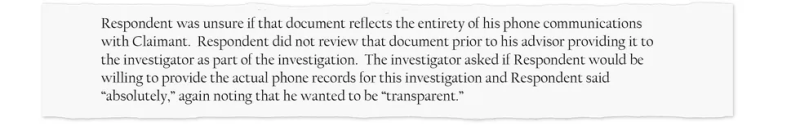

On March 22, the day of his interview, Tucker sent Veidlinger a seven-page written account of his interactions with Tracy and lists of their “currently existing” text message and call history, which he said his legal team had compiled. Only a handful of text messages remained; he and Tracy both told the investigator they had deleted their texts with each other in the months after the April 2022 phone call.

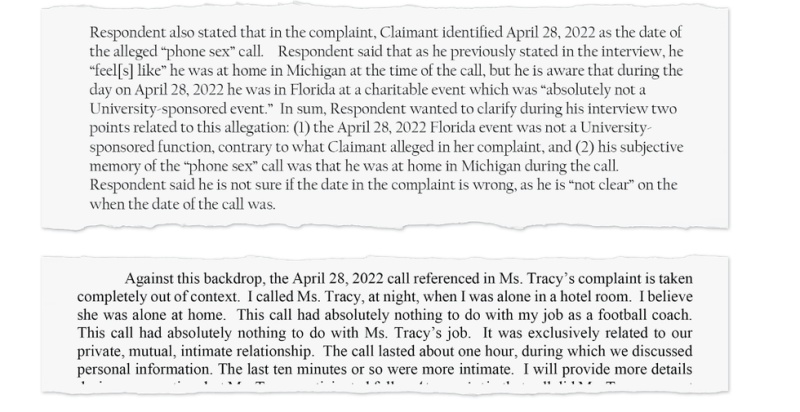

In his interview, which lasted three-and-a-half hours, Tucker questioned whether Tracy had mixed up the date of the call. He said he recalled being at his home in East Lansing when it occurred, but his own records showed that he had been in Florida on April 28, attending a charity function that was “absolutely not a University-sponsored event.”

His seven-page account told a different story – that he had called her while he was “alone in a hotel room.”

Veidlinger does not appear to have asked Tucker about the discrepancy, based on case documents. But by then she knew what he told her in the interview was untrue: she had already obtained records proving he had not been home in East Lansing.

An expense report he had submitted to the university for reimbursement of his hotel and meals shows Tucker flew to Naples, Florida, to attend a golf fundraiser hosted by The Greg H. Montgomery Jr. Foundation for Ultimate Growth, which raises awareness for suicide prevention. It showed he stayed at the Hilton from April 27 to 29, that the trip’s purpose was “administrative” and that it did not involve personal travel. He had flown there on a donor’s private plane.

The trip is when Tucker toured the farm in Immokalee to help promote Michigan State’s College Assistance Migrant Program. The event was titled “Working to make dreams a reality,” according to an agenda obtained from the university by USA TODAY through a public records request. The agenda features Tucker’s name prominently. Tucker posted photos from the tour on his Twitter account.

That Tucker was on a university-sponsored work trip during the incident was a contributing factor in the university’s determination that it had jurisdiction to investigate, the investigation report shows.

Tucker’s lists of calls and text messages also were missing an important detail: They did not show any communication with Tracy on April 28. He acknowledged in the interview, however, that he had not reviewed the lists before submitting them and that they may have been incomplete.

Tracy, meanwhile, had already provided Veidlinger with her official cellphone records from Sprint that confirmed the date of their call: April 28.

Shifting reasons for canceling Tracy’s visit

Tucker and Tracy did not speak in the three months after the April 28 call.

Meanwhile, their assistants were planning Tracy’s third visit to campus – an in-person training with coaches and players scheduled for July 25.

Tucker canceled that training three days before, the investigation report shows. When Tracy spoke to him by phone on Aug. 2 seeking to find out why, she would tell the investigator in her interview, Tucker insinuated he would harm her career if she spoke about his conduct. He never rescheduled her visit, and they never spoke again.

The cancelation became a key focus of the investigator – one of a series of alleged incidents that taken together would meet the definition for sexual harassment, which can include pressuring someone into engaging in sexual behavior for an employment benefit and threatening that rejecting such behavior will carry a negative consequence.

“Reported allegations that a University employee is engaging in misconduct within the vendor-vendee relationship for which they are the decision-maker, and/or impeding in such a services relationship based on a quid-pro-quo sexual harassment allegation, is within a University sponsored program or activity,” Veidlinger wrote in the report, so school policy covered it.

Tucker tried to distance himself from the cancellation in a public statement on Sept. 11, the day after Michigan State suspended him without pay.

“I never cancelled any presentation,” he wrote. “Given a personnel change and scheduling challenges as football season approached, we merely postponed it until January 2023. She chose to file her complaint instead of proceeding with the training.”

But that statement contradicts what he told the investigator. When Veidlinger asked in his March interview if he had a role in canceling Tracy’s visit, Tucker said, “Yes, absolutely I did,” the report shows, and that he did not recall any discussions about rescheduling Tracy for January. Such timing would not make sense, he added, because most of his new players would not yet be on campus.

Tucker also told the investigator why he canceled the visit, blaming it on a scheduling conflict. He said he had recently hired a mental conditioning coach, Ben Newman, who needed to implement his new program on short notice. There was limited time in fall camp, Tucker said, and he didn’t want to “overwhelm” the players. He said he decided to yield the time to Newman.

Veidlinger, however, would later obtain records showing Newman did not meet with the team on July 25, the day of Tracy’s planned visit. He had been meeting with them weekly since June 6, the records showed, but held no meetings between July 15 and July 28.

One of Tucker’s assistants, who is a witness in the case, also told the investigator that Tucker asked him via text message to cancel it. He said he was never instructed to reschedule.

Tucker refuses to name witness who could support his story

In his interview, Tucker told Veidlinger that his relationship with Tracy frayed after the April 2022 phone call – not because of the incident, but because of information he learned after that caused him not to trust her.

According to Tucker, an associate of his had told him over the summer that Tracy’s assistant, Ahlan Alvarado, had been gossiping about Tucker’s marriage, telling others it was “on the rocks.” Tucker said he was “devastated” because he had confided in Tracy about his marital problems, and he believed she had discussed them with Alvarado.

Tucker confronted Tracy about the alleged gossiping during the Aug. 2 phone call, they both told the investigator. Tracy said he berated and bullied her, repeatedly saying he could not trust her. She said she told him she did not know what she was talking about.

Alvarado – who was killed in a car crash in June – would deny discussing Tucker’s marriage with anyone in her January interview with Veidlinger.

During the Aug. 2 call, Tracy said she pressed Tucker to identify his source – the associate. She told Veidlinger she believed Tucker had made it up as a pretext for canceling her visit and ending her relationship with the school.

Veidlinger also asked Tucker to reveal the source of his claim, but he refused to say. In her report, she wrote that he said he had “given (his) word that (he) wouldn’t divulge their name.”

Tucker never revealed the associate’s name to the investigator, nor did he identify anyone who could support his version of events. In his Sept. 11 public statement, however, he lamented that the hearing would not afford him the opportunity to “offer any substantive evidence of innocence.”

It was not the only claim he attributed to his anonymous associate. In his interview, he said that same person told him that ESPN investigative reporter Paula Lavigne was investigating how Tracy “goes about her business” by claiming to be a rape survivor.

Tucker said this further caused him to believe Tracy was untrustworthy, because she believed Lavigne was her friend but didn’t know she was investigating the rape story at the center of her public persona.

It turned out to be yet another falsehood.

Reached by USA TODAY, Lavigne said in an emailed statement that she was “perplexed that Mel Tucker would respond to a complaint of sexual harassment by involving me or ESPN.” She said Tracy has been a source of information for her for several years, and that she has featured Tracy’s comments and advocacy work in multiple news stories.

“That has been the extent of my reporting on Tracy and her organization,” Lavigne wrote. “Neither the organization nor Tracy is or has been the target of any investigative reporting.”

Asked who might have told Tucker this misinformation, Lavigne responded, “I have absolutely no idea who would have alleged this to anyone.”

Kenny Jacoby is an investigative reporter for USA TODAY covering sexual harassment and violence and Title IX. Contact him by email at kjacoby@usatoday.com or follow him on X @kennyjacoby.

Contributing: USA TODAY reporter Steve Berkowitz.

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.