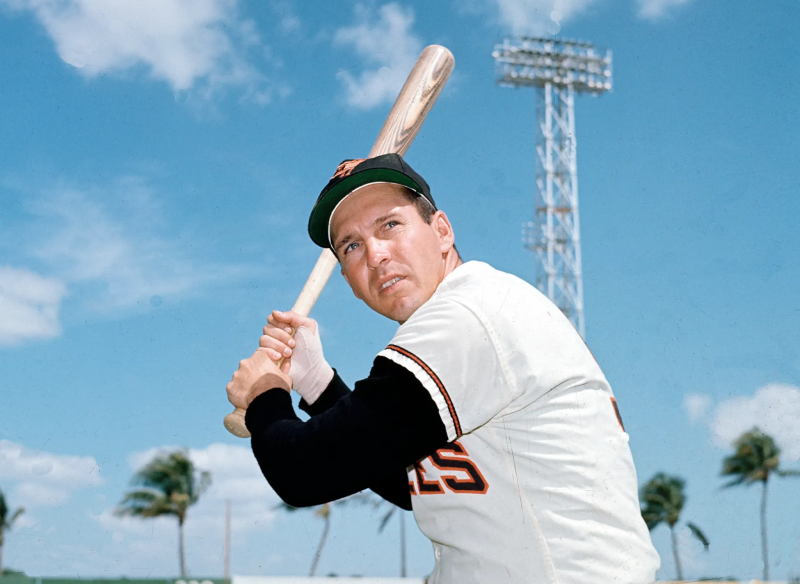

Brooks Robinson, Baseball Hall of Famer and 'Mr. Oriole', dies at 86

Baseball Hall of Famer Brooks Robinson, who died this week at the age of 86, developed an affinity for Cooperstown early in his career.

Standing on historic Doubleday Field during the 1961 Hall of Fame Game, the Baltimore Orioles third baseman heard the public address announcer interrupt the game to announce the birth of his first son, Brooks David.

They would both be in Cooperstown in 1983 for the induction of arguably the game's best defensive third baseman.

Robinson was 24 when the first of his four children was born and was just beginning to display the skills that would bring him fame. That season was already the seventh of his 23 in the majors – he debuted as an 18-year-old in 1955 – and all with the Orioles.

The Orioles organization announced Robinson's death on Tuesday.

FOLLOW THE MONEY: MLB player salaries and payrolls for every major league team

“We are deeply saddened to share the news of the passing of Brooks Robinson," the club said in a statement before holding a moment of silence prior to Tuesday night's game at Camden Yards. "An integral part of our Orioles Family since 1955, he will continue to leave a lasting impact on our club, our community, and the sport of baseball.”

Said Major League Baseball commissioner Rob Manfred: "Brooks stood among the greatest defensive players who have ever lived. He was a two-time World Series Champion, the 1964 American League MVP, and the winner of 16 consecutive Gold Gloves at third base. He was a model of excellence, durability, loyalty and winning baseball for the Orioles. After his playing career, he continued to make contributions to the game by working with the MLB Players Alumni Association.

“I will always remember Brooks as a true gentleman who represented our game extraordinarily well on and off the field all his life. On behalf of Major League Baseball, I send my deepest condolences to Brooks’ family, his many friends across our game, and Orioles fans everywhere.”

That '61 season was when he was picked for the All-Star Game for the second of 15 consecutive times. And it was when he won his second of 16 Gold Gloves (only pitcher Greg Maddux, with 18, has more).

Defense got him into Hall

That's how a player with a .267 batting average gets into the Hall of Fame on the first ballot. Sure, Hall of Fame third baseman Mike Schmidt also hit .267, but his 548 homers were more than double Robinson's 268. Defensively, there was no contest.

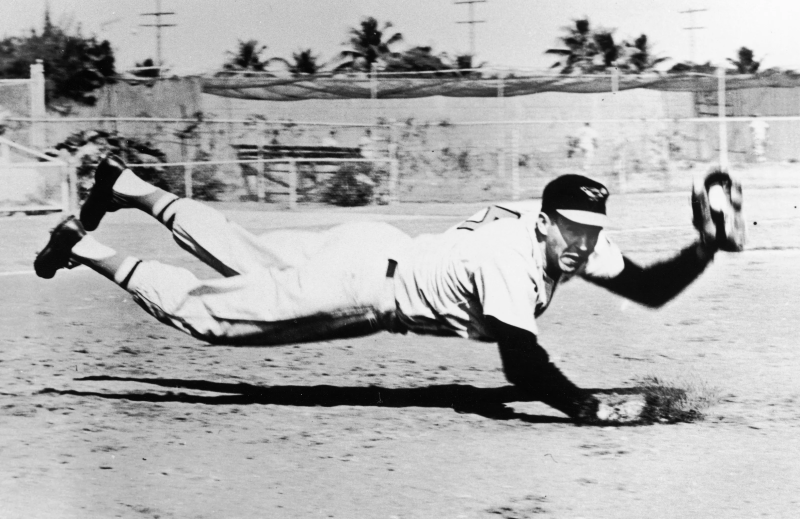

"That kid plays third base like he came down from a higher league," umpire Ed Hurley once said of Robinson.

The humble, personable Robinson endeared himself to the predominantly blue-collar Orioles fans. The nation truly took note of him as a defensive wizard when the Orioles played the 1970 World Series against the Cincinnati Reds.

That was the first Series played on artificial turf, when the teams were in the National League city and the Big Red Machine was accustomed to overpowering the opposition on its field.

But Robinson caught everything, and made the long throws from every imaginable angle to frustrate the Reds – all on the national TV stage.

After Robinson was selected MVP of that Series, an honor that came with a car, Cincinnati catcher Johnny Bench said, "If we'd have known he wanted a new car that bad, we'd have chipped in and bought him one."

Robinson hit .429 with two homers and six RBI in the five games to go with show-stopping defense – and all his teammates did was shrug.

"We kind of laughed at the fuss everyone made," said Orioles pitcher Dick Hall. "We'd seen him make those kinds of plays for years."

There was nothing Robinson enjoyed more, beginning as a youngster in Little Rock, Arkansas, than working on his defense. He would spend hours throwing golf balls and tennis balls against the steps of his boyhood home.

"I always caught it," he once said. "Hand-eye coordination, for sure. That was a God-given talent, and I had it."

There was one other advantage. Like few others, Robinson wore his glove on his dominant hand. He did just about everything else in life left-handed – except play baseball.

"I loved playing the field," he said. "It sounds simple, but I enjoyed catching the ball."

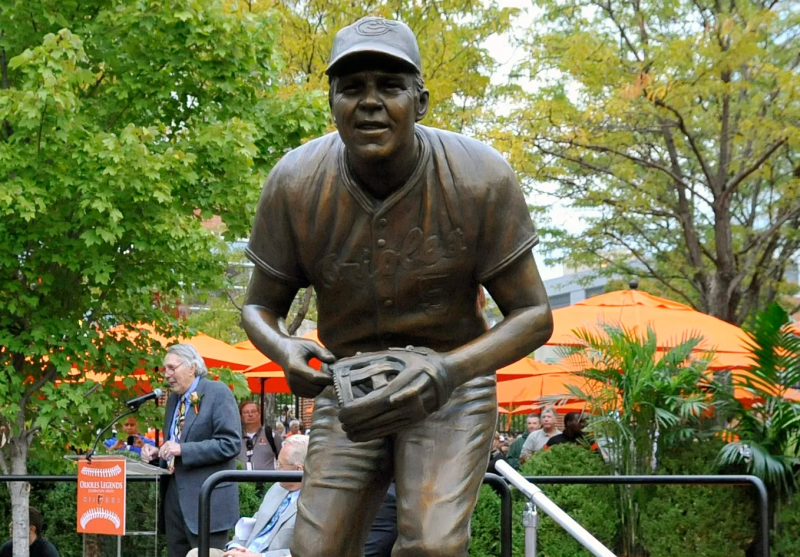

The statue unveiled in 2011 in downtown Baltimore depicts Robinson throwing out a runner. He got a second statue a year later at Oriole Park at Camden Yards as part of a series honoring the franchise's Hall of Famers.

Switching positions

From 1961-73, Robinson averaged 157.5 games a season, a figure that would be remarkable anywhere but Baltimore, home of Cal Ripken Jr. But it was The Ironman, who became another iconic third baseman and Hall of Famer for the franchise, who said of Robinson, "I can almost feel Brooks' presence when I stand where he stood."

But not in 1955, when the Orioles signed Robinson as a second baseman. He debuted in the major leagues that September, after being moved to third base while playing in the minor leagues at York, Pennsylvania.

"That was the best thing that ever happened to me," Robinson said.

Except maybe for those visits to Cooperstown.

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.