Maryland women's basketball coach Brenda Frese: 'What are we doing to youth sports?'

When she watches her twin boys play sports, Brenda Frese is quiet. She stays out of the way. She never interferes, never shouts instructions.

She’s tempted, though. Sometimes she’s really tempted.

"People get all consumed by the ego and just winning at a young age," Maryland’s women’s basketball coach for more than 21 seasons tells USA TODAY Sports. "I remember my kids started basketball, and they’re being put in a zone defense to win a game. And I’m like, ‘What are we doing?’ We should be teaching these kids man before you teach them zone because they need to learn the game.

"We’re not trying to win a game for 12-and-under basketball."

She laughs. Frese restrains herself from talking much during these games. She says plenty internally.

"I watch things being driven by adults," she says. "I would sit at soccer games and cringe when we’re, as adults, ripping officials. My son now referees for soccer and has had parents go after him and others in the parking lot."

Frese might be describing someone you know, or perhaps even describing yourself. If that’s the case, here’s a tip: This national champion and two-time national coach of the year doesn’t do it herself.

"What are we doing to youth sports?" asks Frese, who is approaching 650 wins as a Division I head coach. "It’s not that serious. We’re taking the joy away. I watched one soccer game where a dad completely obliterated his kid who was the soccer goalie ’cause he kept getting scored on.

"Just watching some of the temper tantrums by adults makes you sad for the kids and their only time to go through a journey with sports. And to see that joy stolen from ’em makes me really upset when I sit and watch it because it shouldn’t be that way."

Frese has coached college basketball for three decades, but she’s a mom first, to sons and, in many ways, to her team. She is following a path paved by her parents, Bill and Donna Frese, who raised six kids stretched 14 years apart in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. Bill and Donna worked two jobs yet Brenda doesn’t remember them missing a game.

Another point even more poignant when considered today: When they were there, they mostly sat and watched. And cheered.

"Those are the parents for me in our program that I gravitate (to) the most," Frese says, "and it’s ironic. When you see those kind of parents, those are the kids that are the most successful because the pressure isn’t put on them through their parents. The parents aren’t living vicariously through their kids. It’s a supportive role."

COACH STEVE: When should your kid specialize in a sport?

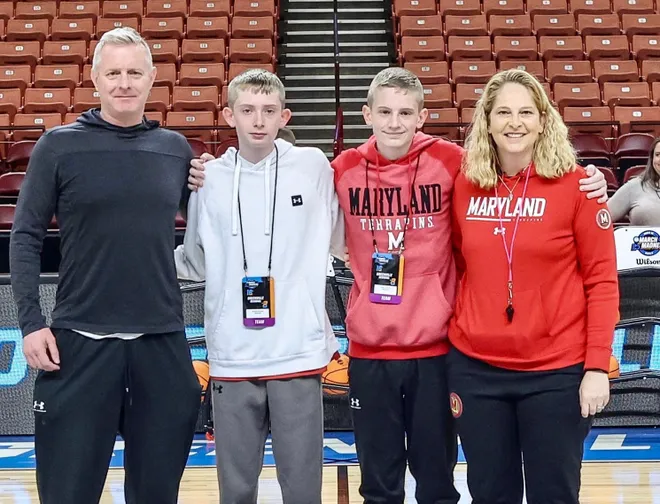

Brenda and her husband, Mark Thomas, are nudging sons Tyler and Markus, 15, forward as they play high school basketball with similar support, and a healthy dose of foresight. The physical and emotional development of their sons has occurred alongside Brenda’s elevation of a women’s program that has remained elite while standing on a foundation of family values.

"She really understands that it’s a huge compliment when families trust us with their kids," Thomas says. "She always likes to give the players six days off at Christmas so they can get home and see their families. And even if we’ve had kids who are from oversees, she’ll let them go home, even if they have to miss a game, to be with their family. And I think that’s pretty rare. And I think being a parent yourself gives you a unique understanding of young people and the growing process."

USA TODAY Sports caught up with Frese and Thomas, who reflected on their roles as sports parents, sharing insight you can use, too.

1. Use sports to help 'find your passion'

Our kids often do what we do, especially when it comes to sports. Bill Frese played lots of different sports growing up. It was natural for him to put his kids into as many of them as they could handle, from swimming to track to softball to baseball, basketball and golf.

The process of trying out a lot of sports, Brenda Frese says, opened the eyes of she and her siblings “to go find our passion.”

"What I appreciated out of sports," she says today, "was anytime, say, you had a bad game, it was never brought up in the car. If, the next morning, you wanted to talk about it and you went to him, then you’d have a conversation. But it was never on him to navigate. He truly made it our passion."

Most of the Frese siblings played two or three sports into high school but settled, by themselves, on the one they loved. So did their father. When he got home from work, Bill Frese would pull his truck up to the family’s large backyard and field baseballs for Brenda’s brother, Jeff, as Jeff hit off a pitching machine Bill got for him.

Other times, Bill would take Brenda and her sisters to a nearby gym. He rebounded for them, ball after ball, until they couldn’t help but get better.

Brenda now watches her sons rebound as her Maryland players shoot before games, framing their experience with her own youth sports as a backdrop.

"My boys have gravitated toward basketball I think just because they’ve been in the gym so much, but they know if they want some kind of training, they need to ask," she says. "I’m not gonna be the one to go force some sort of coaching or training on them. If I go to a game, I’ll always take notes and they know that the notes are for feedback if they want it. I never bring it to ’em. It’s more just, like, they have to want to receive it or ask for it."

As a boy growing up in Maryland with working class parents like Brenda’s, Thomas, her husband, remembers the lack of organization of his sports as part of the fun of them.

"We basically imitated what we saw on TV," Thomas says. "There was no industry of trained coaches, or trained skill trainers like there are today. It was usually just somebody’s dad coaching you and you might have gotten a T-shirt that said 'Academy Ford' on it."

When he threw their kids into sports — basketball, soccer, tennis, gymnastics, lacrosse, one tried football — Thomas realized much of the carefree nature of his childhood games was gone.

"At (an) early age, it seems like they’re trying to take over your calendar," he says. "What I quickly learned was, playing multiple sports gave us a little bit of leverage because I could say, 'Well, we can’t be there 4-5 days a week because he’s playing another sport.'

"Eventually, you may have some hard-line coaches."

When Markus was in seventh grade, one of them said to players and parents, according to Thomas, “We expect you to only play soccer now and if you’re not just playing soccer, then we don’t want you.”

Markus’ response: “I’m done with soccer.”

"He liked playing soccer, but he wasn’t gonna give up playin’ basketball," Thomas says. “It’s too bad because he enjoyed that team, he had friends on it, but those were his words: 'I’m not giving up basketball.' "

2. Work as a family

Brenda and two of her sisters, Marsha and Stacy, played Division I basketball. Jeff played D-I baseball at the University of Northern Iowa.

Injuries ended Brenda’s playing career at Arizona after three years (1989-1992) and she got into coaching. Her third stop was Iowa State, where she was an assistant and also a coach for her sister, Stacy, for four years. Coaching, from that point forward, became a family affair.

"I think I always remember I’m coaching someone else’s daughter because it is a village," she says. "That parents have entrusted me with their daughters in what I think are the most impressionable years, when they’re no longer at home and you’re caring for them. It’s something that I value and want to be very supportive and help them as they navigate those next steps in their journey of adulthood when they’re under our watch in college."

Brenda and Mark met when he produced a weekly, all-access TV show she hoped would bring exposure to her program. It was called “Under the Shell,” a title to which Frese gave meaning when their boys were born on Feb. 17, 2008.

"Brenda’s the only coach that would allow, basically, the reality TV show to follow her pregnancy and be in the delivery room," Mark says.

It was a point when Frese, her family and her program became entwined. The bond was strengthened further when Tyler fought leukemia as a younger boy and Bill Frese died of prostate cancer in 2022.

Frese’s adopted family rallied around her in both instances, as she has done for players and assistant coaches when they have needed her. She admits she came to Maryland in 2002 after only three seasons of Division I head coaching experience “trying to survive a contract and not get fired,” but her perspective has drastically changed.

"I didn’t know if I was gonna be good enough," she says. "Things change once you are validated. You gain the confidence, you gain experiences as a coach. Then, as I had a family, I had a son that went through cancer, and I think it slows you down when you’ve had some real-life experiences — that, at the end of the day, it’s just a game, it’s not the end-all, be-all, even though, obviously we’re in a very competitive profession where, if you don’t have success, you’re gonna be let go. ...

"At some point in my career, once you got there, you felt like, 'OK, I can help mentor people.' The winning takes care of itself. My job is to mentor and help (the Maryland players) so I think that’s when it becomes even more enjoyable is when you understand that."

It’s a lot like raising young athletes.

3. Be present and 'give the gift of yourself'

Episodes of “Under the Shell” are still produced. As you watch them, you can see the genuine joy Frese has interacting — speaking, dancing, singing — with her players. She loves to connect with them away from the court (a great idea for youth coaches, too).

In one episode from the recent past, when they part for some time off at the winter holidays to see their families, Frese gathers in her players and says: “Go give ’em the gift of yourself.”

She was talking about herself, too. If Brenda Frese can do it, so can you.

"She is remarkable," Thomas says. "She does every single thing she can, even if it means missing a few hours of sleep, to spend time with our boys. Even a road game when she travels and gets back after midnight, she tries her best to be up early so she can have breakfast with the boys before they go to school."

Her team’s practice schedule usually allows the family to eat dinner together, as her large family once did. Eating together is a crucial time for the family to bond.

Frese takes the time to text with her sons. Tyler, whom she calls her “hype man,” likes to give his opinion on who deserves a team award at the end of a game. She shares daily Snapchats with her boys (they had a streak going at the time of this publication) and television shows they find time to watch together.

"I’ve always felt that it’s kind of my job to never make her feel like she has to choose between her job and her kids," Thomas says. "So, I never, never, kind of present things like that to her. It’s whatever she needs to do, whatever she can do, it’s cool. And the boys, obviously, love their mother and when she comes home, they kind of forget about me, you know, which is understandable."

This time, it's Brenda’s husband who laughs.

4. 'Put yourself out of a job'

Brenda calls Mark "my MVP." He has stepped away from his own career for Frese and the boys. He gets Markus and Tyler to their junior varsity high school and AAU basketball games, and wherever else they need to go.

"I’m sure my husband’ll be happy once they get their driver’s licenses," Frese says.

He has thrown himself into their lives, coaching their teams and reading up on the mental aspects of sports, particularly youth sports. He admittedly has a high standard for coaches. One idea he and I discussed is how kids don’t process instructions that are being shouted from parents in the stands as well as coaches.

"They can’t process either one of them, so you’re really just messing your kid up," he says. "It’s just so counterproductive. It’s embarrassing; it doesn’t set a good example."

COACH STEVE: Sports parents, you're out of control. Behave or get off the sidelines

Markus and Tyler were certified as youth soccer referees at 13. (Remember, the next time you are tempted to shout at a ref, know that the teenage referee is someone’s child, too.) As they worked a travel game between kids Thomas estimates were 11, parents constantly chirped at the referees, particularly a middle-aged center ref.

When the game was over, Thomas and his son saw at least one parent follow this ref to his car. They caught up with him and made sure he got there safely.

"My son got a full look at that reality and what people are like," Thomas says. "Nothing happened other than the guy wouldn’t shut up as the referee was walking to the car."

Brenda’s schedule prevents her from getting to most of these games but Mark still takes Markus and Tyler to see her coach. As they have watched her over the years, Mark notices, they seem to know when stuff at their practices or games doesn't make sense.

"They have a totally different perspective and take on their own coaches," he says. "Having grown up around mom at her practices, seeing how the program runs ... I just think she’s been involved at such a level that she sees the silliness in people going overboard at these youth sport events that, in the big picture, are relatively meaningless."

Her boys have been living sports — watching them, talking about them, observing them — most of their lives. Is it too early to foresee them, like their mom, having a career in them?

"God, I hope not," Frese jokes.

Like when she’s at their games, she’s going to let them control the outcome.

"I always give the line to our kids, 'Players play, coaches coach, officials officiate; I think parents should support,' " she says. “Your job as a parent is to put yourself out of a job, teach your kid to be independent and be ready for the real world. But, for sports, just be supportive. You've had your path. Your kids just need to know that you love ’em and support 'em regardless if they play well, or don’t play well. I think that’s where they can have a great experience and have a great passion for what sport they find that they like to do."

Steve Borelli, aka Coach Steve, has been an editor and writer with USA TODAY since 1999. He spent 10 years coaching his two sons’ baseball and basketball teams. He and his wife, Colleen, are now sports parents for a high schooler and middle schooler. His column is posted weekly. For his past columns, click here.

Got a question for Coach Steve you want answered in a column? Email him at sborelli@usatoday.com

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.