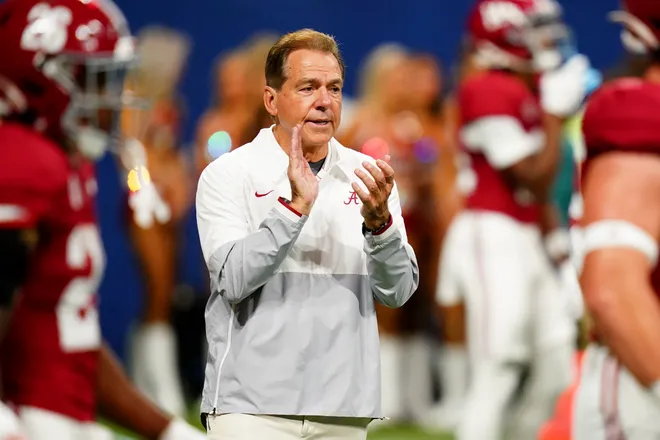

Nick Saban's candid thoughts on the state of college football are truly worth listening to

When Nick Saban says that the current climate around college athletics made it difficult for him to get the same buy-in from players that had previously helped his program sustain dominance from year to year, it’s worth listening to.

But it's just as important for college athletics to take the right lesson from what he’s saying.

In comments to ESPN that will surely make a splash among those pushing for so-called “guardrails” around name, image and likeness payments and the current transfer free-for-all, Saban acknowledged to a greater extent than ever before how those developments factored into his decision to retire almost two months ago.

“I thought we could have a hell of a team next year, and then maybe 70 or 80% of the players you talk to, all they want to know is two things: What assurances do I have that I’m going to play because they're thinking about transferring, and how much are you going to pay me?” Saban said. “Our program here was always built on how much value can we create for your future and your personal development, academic success in graduating and developing an NFL career on the field.”

“So I’m saying to myself, ‘Maybe this doesn’t work anymore, that the goals and aspirations are just different and that it’s all about how much money can I make as a college player? I’m not saying that’s bad. I’m not saying it’s wrong, I’m just saying that’s never been what we were all about, and it's not why we had success through the years.”

There’s a lot to unpack from that comment, so let’s do the best we can without defaulting to how many times Saban got his contract extended and the $11 million-plus salary he was making by the end of his tenure.

While it's always easy to point the hypocrisy meter toward highly-paid coaches who complain about the way things work these days, it’s worth digging a little deeper here.

The quality that made Saban the best college football coach of all time was his ability to adapt. From year to year, he recognized better than his peers how the game was changing and had the capacity to change along with it — even if certain things went against his core beliefs.

Whenever Saban would whine about a certain rule change or how up-tempo offenses were getting the upper hand on his defense, it usually sounded like a threat because he would quickly proceed to turn whatever was nagging at him into an advantage.

People throughout college football assumed that would again be the case when NIL and unfettered transfers became part of how everyone had to do business. But in reality, those rule changes did more to spread the talent around than it did to help Saban collect blue-chip recruits.

Alabama still had its appeal, and Saban's track record for putting players in the NFL was unimpeachable. But for players whose top priority was landing a big NIL payday up front, Alabama wasn't necessarily the choice. The recruiting advantage Saban enjoyed for so many years had been neutralized at least a little bit by everyone’s ability to offer NIL money. The game changed.

It’s not surprising that one of the great consequences of this new money-oriented world in college football was that players would use the threat of transferring to demand higher pay and more job security. After all, that's exactly what coaches do.

It’s also completely understandable how such an arrangement would alter the relationship Saban had previously enjoyed with the blue-chip recruits who chose to play for him. If players were no longer convinced that the long-term developmental advantages of playing at Alabama were greater than the amount of NIL money they could make at other programs, then the system that made Saban dominant for so long would begin to show cracks even he couldn’t paper over.

At age 72 and with little remaining that could add to his legacy, why try to swim against those currents?

It’s healthy that Saban is now talking about this in an open and honest manner. Even if you completely support the athletes’ right to profit off their NIL and believe the NCAA was wrong to restrict it for so many years, it’s a shock to the system. Especially in the current environment, where there are essentially no rules around NIL, it’s not necessarily a complaint to point out the challenges and unintended consequences that are occurring in locker rooms all across the country.

It’s just the new reality.

But for the better part of three years, the response to that new reality from administrators, coaches and other stakeholders has been to look for ways to restrict NIL and put the leverage back in the hands of schools.

Unfortunately for the NCAA and its members, one court after another has found any attempt that even resembles a restriction on how much college athletes can earn to be a violation of antitrust law. And that toothpaste is never going back in the tube.

Bemoaning this new world or prodding lawmakers like former football coach Sen. Tommy Tuberville (R-Ala.) to sponsor restrictive, grandstanding bills that have no chance of becoming law won’t cut it anymore.

The only path forward is an acknowledgement that college athletics will not be stable until schools recognize athletes as employees and collectively bargain with them.

Even someone who wants college football players to make as much money as possible would most likely agree it's not ideal for an Alabama player to go into Saban’s office after every season and demand more money and guaranteed playing time or they’ll enter the transfer portal.

It’s not just problematic for the coach or college football writ large, in many cases it's probably bad for the player as well.

But the takeaway here isn’t that college athletics should go backwards. It can’t. So the only way to calm this chaos is to follow professional sports leagues who work with their players’ unions to set the rules of the road.

Would there be complications for such an arrangement, especially when labor laws vary by state? Yes. Are there Title IX and gender equity issues to figure out? Of course. Will some schools struggle to keep up if they have to pay salaries to their athletes? Most likely.

But this is now a binary choice: College sports can either keep doing things the way Saban described, or it can get real.

For the NCAA and most of its members, negotiating with a players' union would be a last resort. We saw this reaffirmed as recently as Tuesday when Dartmouth’s men's basketball team voted to unionize and the NCAA's response was to reiterate the athlete-friendly proposals it has in the pipeline and call on Congress to pass a law ensuring college athletes won’t become employees.

But the longer this stalemate goes on with little hope of Congressional action and more light being shined on how messy things are in this environment, there aren't many places left to turn.

College sports can choose order through action or disorder through complaint and complacency. Saban’s words should be a warning that the latter is no longer the best option at their disposal.

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.