What do you really get from youth sports? Reality check: Probably not a college scholarship

Here’s what a former Olympic gold medalist says about your development as an athlete: You don’t want to be good.

Pat Powers knows the feeling of just wanting to be adequate. He wrestled in the 112-pound weight class in high school. He was 6 feet tall.

“I think I set the state record for getting pinned,” Powers says. “It was like 14 seconds or something.”

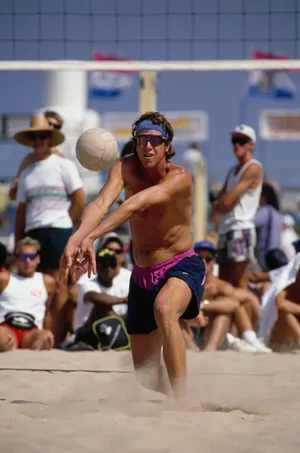

But when he grew to 6-5 and 218 pounds, Powers won gold as an American volleyball player in 1984. He was a powerful, aggressive hitter for Team USA. Four decades later, he takes a similar approach when he faces down sports parents at volleyball camps and clinics he hosts around the country.

He levels with them about their kids’ chances at world-class sports achievement. It’s possible, of course, but you also need physical gifts.

And being "good" shouldn't be your goal.

"It's not how good you are, it’s how good you're getting," he says. "That's your team character. That's your mantra. That's your culture.

“You don't want to be a good player because if you think you're a good player, trust me when I tell you, there's players out there a lot better than you that are gonna humble you.”

Powers, 66, drives hard realities into parents’ thinking about their kids’ sports futures. But they’re only hard if you lose sight of the rewards of sticking with your sport anyway.

After years of careful observation, Powers has come up with “seven rules of junior sports.” During an interview with USA TODAY Sports, he discussed how these rules can serve as a reality check for you and your athlete.

What are you really gaining from their sports? Hint: Don't bet on it being a college scholarship.

(Questions and responses are edited for length and clarity.)

1. Every player thinks they're better than they are

If you tuned into the NCAA men’s volleyball championships this past weekend, or watch the NCAA men’s and women’s basketball tournament in March or Big Ten or SEC football on fall Saturdays, you might have already recognized your kid’s limitations as an athlete.

Powers won a state volleyball title with Santa Monica Junior College (California) in 1977 and a national title with the University of Southern Cal in 1980. At some point in those years, he realized, “All of a sudden, I could jump and just hit the living daylights out of a ball.”

If you don’t have size and sheer strength, embrace what Powers calls the “Holy Grail” of sports and life: The ability to change in practice. Instead of seeing yourself as “good,” focus on how much better better you can get each day.

That’s easy, Powers says, when everyone is trying out or looking to impress the coach. But what about when the comfort of routine and familiarity of a season sets in?

USA TODAY: What was the biggest key to your success?

Pat Powers: Back when I played I could touch like 11-4, 11-4 1/2, 11-5. And back then that was pretty good. Just to give you an idea of today's players, they're touching 12 feet. These guys are so much bigger and stronger.

With the kids, I’m really honest. Because the first thing a college coach is gonna ask is, "What do you touch?" It's a physical metric they look at. If you're a girl and you touch 10 feet, the chances of you playing in college are extremely high. But if you're a girl and you touch 9 feet, 6 inches, you're not going to play in DI at a high level. It's just not gonna to happen. Sorry. The sport's just too brutal. The players are just so strong.

What do you touch is the most obvious question, but the other part is your capacity for change. How much can you change in the sport? Can you get better season to season? Can you make players around you better? Can you learn new techniques? Are you just stuck on one thing and you're not gonna learn?

2. Every parent thinks their kid is better than they are

How can we change if our parents reinforce, if not outright endorse, the belief of how good we are?

Try focusing on being a good teammate over being a good individual player.

USA TODAY: What do you think is the biggest key to be a good teammate?

PP: I think one of the reasons that Caitlin Clark had so much success at basketball is she just seems like a really good kid. I think she's a great role model for these kids because she seems like somebody who's a great teammate (and) she makes the players around her better.

This is what Karch (1984 Olympics teammate Karch Kiraly) was so good at - making players around him better. And you do that on the court with your play, you do it during practice with your ability to change and your innate ability to make yourself better. The only thing you can't do is make other players around you worse. And you can’t do it with your attitude, the way you conduct yourself, the way you talk to other players, because that's the cancer. When you let players start doing that, it just spreads onto the team.

COACH STEVE: How to be a good loser, like Caitlin Clark

3. Everybody wants to play with better players (and 4. Nobody wants to play with worse players)

Powers says parents “get suckered" into putting their kids on the strongest possible team. Being on this team, they think, can be validation for their kid's ability. But often, he says, it's more about making money.

"Why do club directors fill out their rosters with these extra players?" Powers says. "Revenue."

USA TODAY: How can these rules be a turning point in a player’s sports career?

PP: The most common thing that happens is players are given a choice (of teams), which makes it even more evil because the club director puts it in the parents’ hands. They go, "Look, you can play on our three team and you're probably gonna to play about 50 to 70% of the time. Or you can play on our two team, and you're probably gonna play about 25 to 40% of the time," somewhere thereabouts, and it’ll be more merit based. And what they don't realize is they're the 10th, 11th and 12th player on the club team and they're not playing as much.

Come February, you're playing teams exactly like yourself, you're not winning. You go to a tournament, (and) that club director and the coach say, "We're gonna play our best players until we can no longer win the tournament." One thing builds (on) another. The way that volleyball works going is from (ages) 16 to 17, there's just a massive drop-off because parents and players both finally realize that they're being monetized.

COACH STEVE: 70% of kids drop out of youth sports by age 13. Why?

5. The higher the level of the team, the greater the chance of conflict

In volleyball, Powers says, the parents of the top two to three players on a club often don't want the "lower" players on the court at all. If you're a travel sports parent, you know this rule can apply to many other sports.

"That's where all this drama happens," Powers says.

These are also the parents of the players the coach wants to keep on the team, and he or she wants to appease them. Be realistic about your kid's ability if you choose the "A" team.

USA TODAY: Do you oversee a bunch of instruction, or do you coach competitive teams as well?

PP: I do both. My club team is not very good. It's probably one of my better coaching jobs. This year, I'm actually really lucky. My best players are pretty forgiving, and they're pretty understanding, they're pretty supportive of the players that are not as good on the team. If you made a choice of going from the second team up to the first team, really, really good team, and you're the 10th and 11th and 12th player, well, guess what? You're not gonna play as much.

If the club director says (at the beginning of the season), they are going to play the best players all the time, understand what they are communicating to you. Be supportive of your teammates - easy to say, challenging to do. Compliment players when they come off the court. Understand that in sports, people judge your character more after a loss than after a win. Another suggestion is to compete against your fellow players. You wanted to play against better players? Your moment has arrived. Earn your playing time.

6. The 10th, 11th and 12th players are your team's profit margin, but they account for 80-90% of your issues

If you choose the top-tier team, not only might your kid not play, you could be funding the star players with your team dues.

USA TODAY: When you coached men's volleyball at USC (from 1997 to 2002), are there things that you learned coaching kids at that level that now you apply to the younger levels?

PP: It’s a different level of athlete. I don't necessarily talk to players about this, but (volleyball) club directors and coaches, and they all laugh when I say this, because it's the dead-honest truth is, there's more money in bad volleyball than there is in good volleyball. If you're a really big club director, you can make well north of $1 million a year. And it's based on just playing bad players. As a matter of fact, what a lot of people don't realize is, the higher-end players on these really, really good teams, they actually scholarship those players. They’re reducing their fees and the other players are actually paying for that player to play on the team. It's an optical illusion.

Not only are we not charging ‘em for club dues, which could be anywhere from $5,000 to $8000 here in San Diego, but they're going, "Look, not only do have to not pay dues, but we're gonna pay for your flight to all four tournaments and get you a hotel." It's starting to emulate what the NIL is doing.

7. Everybody thinks the first 6 rules don't apply to them

This rule plays out until your child reaches a scenario that Joe Trinsey, a former NCAA, professional and Olympic volleyball coach, painted for me.

"She'll be the best or second-best player on her ‘National’ U-14 team and be a good player on JV as a freshman,” he says. “Despite making varsity as a sophomore, you'll realize that there's a whole other level beyond your kid. This realization will probably occur when walking by a convention center court that you think must be the 18s championship only to realize that they are also U-15s. If you're smart, you'll settle in and enjoy her remaining high school (and club, if you can afford it) experience.”

If we truly love a sport, we can always revisit the intrinsic value of it. Volleyball, for instance, is a sport you can play in pairs on the beach.

Powers says beach volleyball is the best pay to improve because you're forced to face your weaknesses. But there is also something valuable about being outside with your teammate on a nice day, too.

Always remember that camaraderie and friendship are big reasons we get into sports in the first place.

USA TODAY: Why should a kid start playing volleyball?

PP: The reason you play volleyball is not because you want your daughter to get a scholarship. But the reason you play volleyball is that's where the good kids are. It's a very social sport and we tend to get students who do well in school. I've had professional athletes listen to my talk and they go, "This is like, the only talk I've ever had that people actually explain it and are really honest with what you're doing." What I tell people is, "Hey, the people that make it do one thing: Use the sport of volleyball, use athletics, to further your academic career. That's it." Don't sit here, tell me how you're gonna get a scholarship for this because some of the most successful people are your four-year walk-ons.

Steve Borelli, aka Coach Steve, has been an editor and writer with USA TODAY since 1999. He spent 10 years coaching his two sons’ baseball and basketball teams. He and his wife, Colleen, are now sports parents for a high schooler and middle schooler. His column is posted weekly. For his past columns, click here.

Got a question for Coach Steve you want answered in a column? Email him at sborelli@usatoday.com

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.