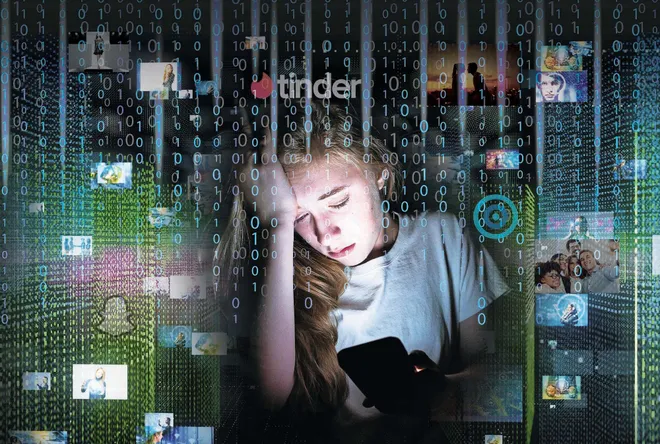

Parents need help regulating their children's social media. A government ban would help.

Parents worry about a lot of things.

But one of our persistent concerns is our kids' smartphones. We justify their use by embracing their necessity. How else can we communicate about school pickups and sports practices?

With that comes access to various minefields, from gaming to social media. As they go off to school and other activities, we wonder if they see things they shouldn't, talk to people they shouldn't or rot their brains with excessive screen time.

The remedies are obvious, just hard to implement: Don't get kids a phone, ban social media or allow social media with boundaries and parental controls. A new federal bill might help parents find a solution.

Parents, children face challenges with social media and smartphones

We know now that excessive social media use increases depression and anxiety. A 2023 surgeon general advisory found that 40% of children ages 8 to 12 are on social media.

Social media and smartphone use have become so commonplace and ubiquitous that it truly does seem hard, if not impossible, to police, given everything parents have going on, including working a full-time job, maintaining relationships, and caring for themselves and their children.

Biden, Trump need extremists to win.It's pushing average voters away.

I have four children, and I'm constantly ruminating over the question: What is more important than my child's physical safety and emotional well-being?

Three of my children have phones, so I've banned social media altogether. They also have limits on their screen time and can't keep their phones in their rooms overnight. I still check their phones regularly but confess that constant surveillance has become an omnipresent task that provides endless questions and few solutions.

What's the best way to help our kids navigate technology?

There are ways to hide social media apps and bypass parental controls. Once kids become teenagers, they're not sitting in the living room 24/7 under parental supervision. They're often in school, with friends, working a job, on an athletic team or maybe playing an instrument. They're busy but still on their phones.

Most parents know that social media use, especially multihour daily use, isn't great for their teen's emotional health, but they still feel ill-equipped to help their teen handle something as big as social media has become. "Did you see that TikTok?" has to be one of the most common refrains in high school now. In fact, fitting in with their peers is probably the only upside to social media if conformity is a plus (it's not).

The downsides are worse than most parents realize. In January, Congress grilled the CEOs of Meta, TikTok and others and revealed that sexual predators are rampant and other negative behaviors like bullying and eating disorders are magnified. Worse, all the executives knew this existed, and while they seemed to be genuinely trying to curb it, their own efforts fell short.

So do parents need the government's help?

This issue is so pressing that it spurred a Republican and a Democrat to co-sponsor legislation that would essentially ban social media for young kids.

If passed, the Kids Off Social Media Act would prevent kids younger than 13 from accessing social media, prohibit social media from programming algorithms for teens under 17, and give schools the ability to block access to social media.

It's part of multiple attempts by lawmakers to place guardrails around the internet for children, including the Kids Online Safety Act.

Congress fails us again:Congress voted against funding a cure for cancer just to block a win for Biden

Sens. Ted Cruz, R-Texas, and Brian Schatz, D-Hawaii, both dads, have paired up to unveil the Kids Off Social Media Act in the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation.

"It’s really hard to be a teenager today. And it is incredibly frightening to be a parent today,” Cruz told The Washington Post. “This legislation is trying to take a meaningful step to protect our kids.”

If passed, it's easy to see how parents everywhere, as well as school administrators and teachers, might sigh a breath of collective relief. However, it seems well within their purview to ban smartphones during class and block access to social media on district Wi-Fi – something that schools in Florida have already done and more are considering. The legislators say they haven't met a parent who doesn't support the bill because they feel pressure for their kids to be on social media.

“The reality of life is there's a moral hazard. And no parent wants to be the one that forces his or her child to be excluded from the school social scene, to be ostracized from their friends," Cruz told me. "And so I've had multiple conversations with moms and dads who are frustrated. They don't want their kids using these devices on these social media sites. ... But I think parents as a whole would much prefer that all the kids be protected. And this bill was designed to strike a compromise."

As a parent, I welcome a federal social media ban for kids

Parental rights advocates on the left might argue that social media helps marginalized children or is their only outlet, even at a young age. Others on the right might balk at a bill that intervenes with their own role as a parent. It's also antithetical, some might say, for a Republican to sponsor a bill allowing a government bureaucracy to intervene in a child's daily habits.

Social media companies won't like the bill, either; they'll claim it's unconstitutional. Cruz, like many conservatives, has departed from the more libertarian, live-and-let-live stance.

As a parent, I have yet to see how rampant social media use for kids under 13 is helpful or good for them, so I welcome a targeted and carefully crafted ban. It takes the issue out of parents' hands, just like laws about driving, alcohol consumption or tattoos. The Federal Trade Commission's enforcement of the ban is tied to the bill, so the FTC couldn't deviate from the text, preventing a slippery slope of additional bans.

Parenting is already challenging. Figuring out how to balance a tool that has become necessary and harmful makes it more so. Kids like mine wouldn't need an adjustment period, and if the bill passes and 11-year-olds become distraught because it's enforced, that might underscore its importance.

Nicole Russell is an opinion columnist with USA TODAY. She lives in Texas with her four kids.

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.