Mass dolphin stranding off Cape Cod officially named the largest in U.S. history

Just over 100 dolphins survived a mass stranding off Cape Cod that started last month, and the event has officially been named the largest mass stranding of dolphins in United States history.

The ordeal began on June 28 in Wellfleet, Massachusetts, about 15 miles southeast of Provincetown, the International Fund for Animal Welfare, a nonprofit, said in a statement. It lasted five days.

Prior to this mass stranding, there were two prior events on record in Hawaii and the Florida Keys where dolphins were seen circling in shallow water. However, this most recent event includes the highest number of dolphins beached in a single stranding event, the IFAW said.

According to the IFAW, it is common for animals to become stranded at the Herring River ‘Gut’ because it is shaped like a hook and there are often extreme tidal fluctuations.

The dolphins were sent to deeper water at Herring Cove Beach in Provincetown.

The IFAW reviewed data and aerial imagery and found that there were 146 dolphins in total who were stranded and 102 survived the event. That’s about a 70% survival rate, the IFAW said via email Monday morning.

Among the dolphins, 37 died naturally, seven were euthanized and 10 were extracted and released.

The dilemma began when dolphins were stranded in shallow mud flats off Cape Cod on June 28, the IFAW said on its website.

Someone made a call about 10 Atlantic white-sided dolphins close to shore off Wellfleet early that morning. IFAW staff and volunteers went to the scene and found 125 animals, but 10 dolphins had already died.

“We arrived to what appeared to be 80 to 100 dolphins on the shallow mud flats of Wellfleet’s Herring River ‘Gut’ – a global epicenter for mass strandings,” said Misty Niemeyer, stranding coordinator for IFAW, on the agency’s website. “We were able to provide supportive care, help those that were struggling, and keep them comfortable and ready for the incoming tide.”

How experts released the stranded dolphins

The IFAW said staff and volunteers herded the dolphins in on foot initially to get them into deeper water. They eventually switched to boats due to the high tide.

Niemeyer, the IFAW’s stranding coordinator, said the crew faced multiple challenges while trying to move the dolphins, including how large the group was, the animals’ large size, how spread out they were and difficult mud conditions.

As the sun began to set, most of the dolphins had found their way to deeper water offshore, the IFAW said. About 12 or more were still swimming in the inner harbor at sunset the night of June 28.

“It was a 12-hour exhausting response in the unrelenting sun, but the team was able to overcome the various challenges and give the dolphins their best chance at survival,” Niemeyer said on the agency’s website.

Community reacts to mass stranding

During the ordeal, the animals went through what felt like a car crash to them, the IFAW said in a video about the stranding.

They underwent exhaustion and trauma and weren't as strong as they needed to be in order to make it back to deeper waters.

As the dolphins washed up, community members became ridden with anxiety and fear for the marine animals, and some called for more protections to prevent such mass strandings.

Katie Carrier is an administrative assistant at a country club along a beach where some of the dolphins were stranded. People began rushing over to try and help the dolphins, who can breathe while out of the water but not for long in direct sunlight.

"We need to be more proactive, so we're not so reactive," Carrier said. She suggested investing in equipment to provide aerial views of dolphin pods so officials can find out about potential strandings ahead of time.

From the community:After mass dolphin stranding, Cape Cod residents remain shaken

Brian Sharp, marine mammal rescue team director at the IFAW, said people who see stranded dolphins should call local stranding responders or 911.

It also helps to shoo away gulls because the birds sometimes eat stranded dolphins alive.

Over 150 people worked to free the animals who were stranded that day, including at least 25 IFAW staff, 100 trained volunteers and representatives from AmeriCorps of Cape Cod, Whale and Dolphin Conservation, the New England Aquarium, the Center for Coastal Studies and the Wellfleet Harbormaster.

Also part of the marine mission were IFAW veterinarians and biologists aboard custom-built mobile dolphin rescue clinic vehicles. There, they were able to give the dolphins fluids and other treatments as they led them to deeper water.

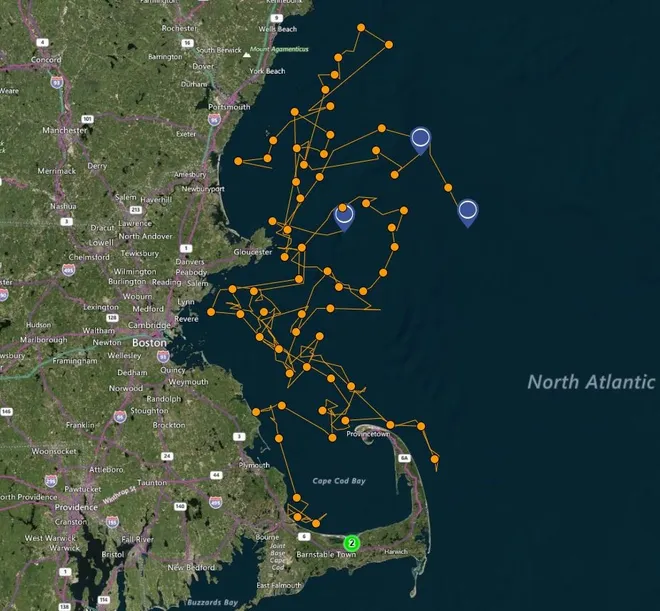

The agency used satellite tags to track some of the animals offshore.

Calling it “a happy image,” the IFAW also said whale watchers have seen the once-stranded dolphins, who have temporary markings, swimming with groups of dolphins that were not part of the mass stranding.

Contributing: Claire Thornton

Saleen Martin is a reporter on USA TODAY's NOW team. She is from Norfolk, Virginia – the 757. Follow her on Twitter at@SaleenMartin or email her atsdmartin@usatoday.com.

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.