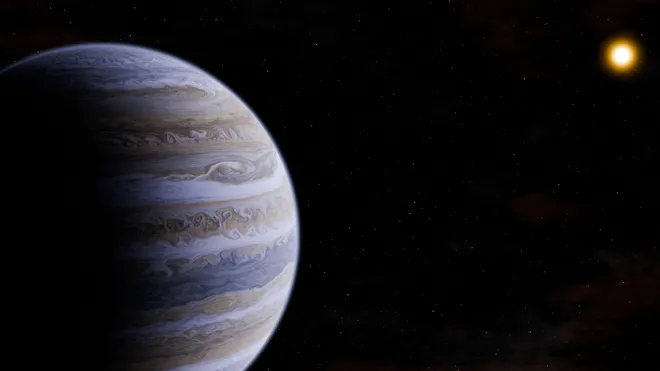

Astronomers detect rare, huge 'super-Jupiter' planet with James Webb telescope

A team of astronomers used the powerful James Webb Space Telescope to capture new images of a "super-Jupiter" planet – the closest planet of its huge size that scientists have found.

The planet is a gas giant, a rare type of planet found orbiting only a tiny percentage of stars, which gives scientists an exciting opportunity to learn more about it, said Elisabeth Matthews, a postdoctoral researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg, Germany, who led the study published in Springer Nature on Wednesday.

"It's kind of unlike all the other planets that we've been able to study previously," she said.

The planet shares some qualities with Earth – its temperature is similar, and the star it orbits is about 80% of the mass of our sun.

But "almost all of the planet is made of gas," meaning its atmosphere is very different from Earth's, Matthews said. It's also much larger – about six times the size of Jupiter, she said.

Matthews' team first got the idea for the project around 2018, but their breakthrough didn't come until 2021 with the launch of the James Webb telescope, the largest and most powerful ever built.

After decades of development, the telescope was launched that December from French Guiana. It has the ability to peer back in time using gravitational lensing, according to NASA.

Astronomers had picked up on the planet's presence by observing wobbling in the star it orbits, an effect of the planet's gravitational pull. Using the James Webb telescope, Matthews' team was able to observe the planet.

More:US startup uses AI to prevent space junk collisions

James Webb telescope helps astronomers find dimmer, cooler stars

The planet circles Epsilon Indi A, a 3.5-billion-year-old "orange dwarf" star that is slightly cooler than the sun. Astronomers usually observe young, hot stars because their brightness makes them easier to see. This star, on the other hand, is "so much colder than all the planets that we've been able to image in the past," Matthews said.

The planet is also even bigger than they had believed, she said.

"I don't think we expected for there to be stuff out there that was so much bigger than Jupiter," she said.

Some scientists believe the temperature of an orange dwarf like Epsilon Indi A could create the ideal environment on its orbiting planets for life to form, NASA says. But Matthews said the planet wouldn't be a good candidate.

"There isn't a surface or any liquid oceans, which makes it pretty hard to imagine life," she said.

Still, Matthews said, it's "certainly possible" that a small, rocky planet like Earth could be a part of the same system; researchers just haven't been able to see it yet.

Although the team was able to collect only a couple of images, Matthews said, its proximity offers exciting opportunities for future study.

"It's so nearby, it's actually going to be really accessible for future instruments," she said. "We'll be able to actually learn about its atmosphere."

Cybele Mayes-Osterman is a breaking news reporter for USA TODAY. Reach her on email at cmayesosterman@usatoday.com. Follow her on X @CybeleMO.

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.