After 26 years, a Border Patrol agent has a new role: helping migrants

EL PASO, Texas – The night's sleeping mats neatly folded to one side, shelter director Michael DeBruhl bowed his head in prayer with the few migrant families who had stayed over.

There were eggs and black beans for breakfast, oatmeal and steaming coffee. DeBruhl greeted them using the Spanish he'd perfected in 26 years as a U.S. Border Patrol agent.

If migration at the U.S.-Mexico border has been one of the most divisive issues in America, DeBruhl has straddled both sides. He has handcuffed migrants and deported them. He has fed migrants and sheltered them. He has survived, in his own heart and mind, a debate that has divided the nation's politics, and its families.

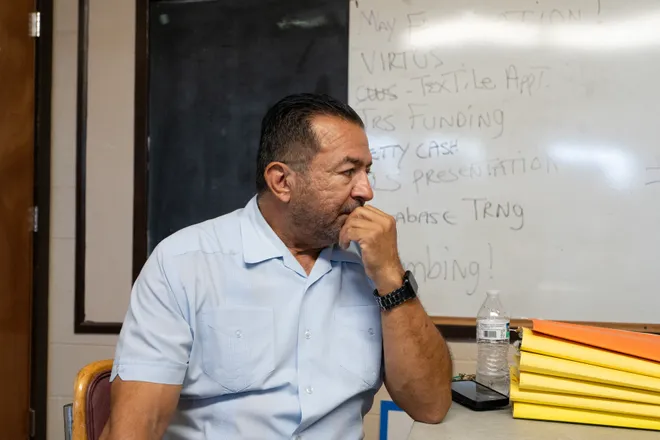

"Immigration is extremely complex," he told USA TODAY. "When I was a field agent, that’s what I understood: I understood enforcement and the intelligence of how people come across the border. But as you rise in the organization, the higher you go, the better the picture is on the larger issues."

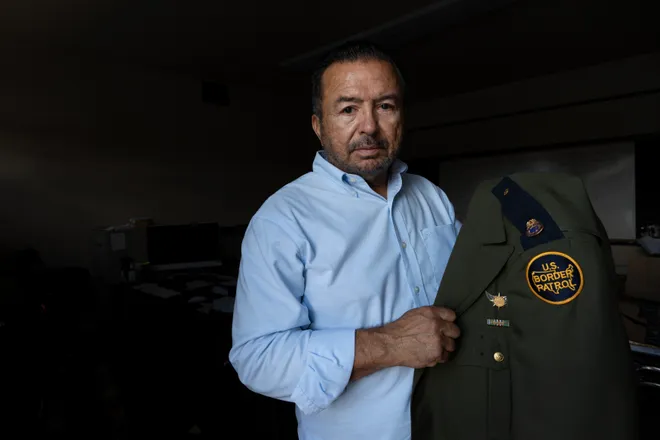

DeBruhl began as an agent in 1989, patrolling the Rio Grande in Texas. Over his nearly three-decade career, he rose to become chief patrol agent of Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands, joined the agency's highly selective Border Patrol Tactical Unit and served in agency leadership in Washington, D.C.

"No one could ever accuse Michael of being some bleeding heart who doesn’t understand the dangers of the border," said Sami DiPasquale, whose nonprofit ABARA provides border immersion programs that include a visit with DeBruhl.

"I think from the outside, people could be really surprised that a Border Patrol agent and chief is doing this work, but in El Paso we don’t see it that way," DiPasquale said. "We know how complicated the situation is. It’s not that one side is purely evil and the other side is purely good. Michael's whole life is an embodiment of why that isn’t the case."

DeBruhl describes himself as "a short guy" who had to have his Harley Davidson motorcycle lowered three inches to let his feet reach the ground. People who know him describe him as both commanding and compassionate.

"You don’t look at Mike and think, 'This is a warm and fuzzy guy,'" said Bri Stensrud, executive director of Women of Welcome, a conservative Christian group that has visited the shelter. "We’re told to pit people against each other and put each other in different groups. You can’t possibly be for humane treatment of migrants and also be for strict law and order ‒ and yet Mike blows all those misconceptions out of the water."

After turning in their badge and gun, many retired agents become investigators, national security consultants or political pundits. DeBruhl retired in 2014 at 55. He took a job as a Homeland Security contract investigator. When COVID-19 hit, he retired again.

Along the way, the nation's immigration politics were shifting dramatically.

"I started hearing that everyone coming across the border is a criminal," he said, "and that the people coming to the United States are being released from insane asylums. We started separating children from their families. I was really bothered by all these things, especially the things that I knew not to be true that were being put out in the press wholesale.

"These were things I couldn’t abide by," he said. "This wasn’t the America I grew up in."

He signed up to volunteer at a local migrant shelter.

From Border Patrol agent to migrant aid worker

In December 2022, hundreds of migrants were congregating on the streets outside Sacred Heart Catholic Church in downtown El Paso.

The church, which sits five blocks north of the U.S.-Mexico border, became a natural magnet for displaced people from Nicaragua, Venezuela and elsewhere who had sought asylum and were processed and released by Border Patrol.

The weather was cold, and children were sleeping on cardboard outside. Father Rafael Garcia opened the church gym as a refuge – without staff, volunteers, supplies or a plan. A mutual friend who worked in migrant aid told the Jesuit priest to call DeBruhl.

On one of his last missions in the Border Patrol, DeBruhl served as chief of staff for a campaign in South Texas that brought together multiple agencies under one roof to target migrant smugglers, drug traffickers and the criminals ferrying firearms and currency into Mexico.

He was fluent in the language of law enforcement, telling U.S. Customs and Border Protection's Frontline magazine in 2014 how the campaign "brings to bear the full capabilities of our federal, state and local resources. It is the system working as it is designed to work; interdictors, investigators and prosecutors achieving an outcome in confluence.”

Border Patrol agents like to say they are adept at handling logistics; it's part of the job. Migration patterns are constantly shifting. The circumstances of who is arriving, how and in what condition are subject to change – sometimes overnight.

When Garcia called him for help, DeBruhl saw a humanitarian crisis on the streets of his hometown that troubled him. He also viewed the problem as an agent might: as a logistical challenge to be solved.

"There were 1,000 people outside," DeBruhl recalled. "All the news agencies were out there also. I was surprised to be cast into the middle of the whole thing."

He got to work: ordering camping mats that could be folded up in the morning to create play space for the children, organizing a massive pile of clothing donations into racks and shelves like a proper thrift store, staffing the kitchen to provide meals and organizing volunteers to help migrants get on their way.

His shift from agent to aid worker raises eyebrows among some current and former agents; others say they can understand the impulse to act on one's compassion.

"Here’s what I’ll say about the choice Mike has made," said Pete Hermansen, who served two decades in Border Patrol, including in leadership alongside DeBruhl. "Eighty-seven percent of the illegal aliens that cross that border, in my experiences over 22 years, are just coming across to better their lives. Thirteen percent are people we don’t want here. Taking a position to help the 87% I think is a noble cause."

Historic period of migration winds down

DeBruhl is deeply proud of his service in the Border Patrol. Yet when he retired, he envisioned starting a new chapter, he said, and didn't keep in touch with former colleagues. Nor did he tell them about his new work.

He did talk to Garcia, the priest.

"When I talked to the father about it, I said, ‘You know, I’m not here because of any religious calling,’" DeBruhl said. "He said, ‘Well, I’m not so sure about that.’"

Sacred Heart has sheltered or provided services to more than 30,000 migrants since that December, Garcia said, reflecting a historic period of immigration at the U.S.-Mexico border.

Between December 2022 and July 2024, CBP registered more than 936,000 migrant encounters in El Paso Sector alone. There were months where migrant encounters topped 50,000 and every shelter in town was bursting.

But the historic period appears to be winding down. In July, the number of migrant encounters in El Paso Sector dropped below 12,000 for the first time since 2021, according to CBP, echoing a sharp drop all along the U.S. southern border.

Just a couple of dozen people were at breakfast one morning in late August. They would mostly all be gone within a day or two, headed to reunite with family members across the U.S. or start new lives in New York, Chicago or Denver on their own.

Nearly all had crossed at a port of entry, utilizing the CBP One cellphone application to make an appointment to enter the United States – one of the many shifting border dynamics DeBruhl explains when curious Americans come to visit. He spends hours giving talks to faith groups and business leaders, hoping his distinctive perspective might make an impression.

"Looking back, there was one day when I realized I was in the right place," he said. "I am in a unique position. I can add some fidelity to this discussion we’re having – or not having – about immigration policy. What are the things we are doing right? What are the things we’re doing wrong? What discussions are we having or not having? What is true and not true?"

What is true now is that there aren't enough migrants arriving to justify keeping the shelter open, and DeBruhl plans to close its doors on Oct. 7.

Lauren Villagran can be reached at lvillagran@usatoday.com.

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.