Meals on Wheels rolling at 50, bringing food, connections, sunshine to seniors

WEST CREEK, New Jersey − Regina Cippel has some simple advice for a long life: Rest when you need to. Don't demand a lot, and be thankful for what you have. Work for as long as you can. Be helpful to others.

And eat well.

It's hard to argue with any of that: Cippel is 101, but she looks and sounds like someone at least a few decades younger. She dispensed the advice after lunch but before a spirited game of seated volleyball at the Ocean County Southern Service Center, where Meals on Wheels hosts seniors for activities, a meal and socialization.

Cippel is one of hundreds of seniors who get prepared, nutritious food from Meals on Wheels of Ocean County, and one of the millions who benefit from Meals on Wheels America, the umbrella organization supporting more than 5,000 community-based programs across the country.

But in 2024, as Meals on Wheels marks 50 years of serving older Americans, it's also facing daunting challenges: Prices for food and fuel are rising, while federal funding has remained flat and even dropped.

There are fewer volunteers to prepare meals, load trucks and deliver meals to people who can't drive because of age or disability. And as baby boomers age, more of them need the help as they outlive their savings and as the cost of living keeps increasing.

More than meals

"Most people think we're about a nutritious meal being delivered to one's home, but it's much more than that," said Ellie Hollander, president and CEO of Meals on Wheels America.

"The meal is an entree to social connection, to someone who has their eyes and ears on a senior who might not always see someone."

Many of the meals are served in community centers, senior centers and other communal settings, Hollander said. Those who can pay are asked for a small donation (usually about $4 a meal).

At the Ocean County Community Center, Cippel and about two dozen other seniors painted pumpkins, ate lunch, chatted, got a quick lesson in Spanish vocabulary words and did some chair exercises.

After her husband died 10 years ago, Cippel had Meals on Wheels delivered to her in Barnegat. A year ago, she moved in with her son, who died recently, and daughter-in-law at their Little Egg Harbor home.

She enjoys her trips to the lunches: "It's great. They go out of their way to make things interesting." The grandmother and great-grandmother likes getting out of the house, talking with other seniors, and, judging by her laughter and the force of her serve, chair volleyball.

"It's good to get out with friendly people," Cippel said. "I can relax and enjoy myself, and it takes my mind off loneliness."

'Food is medicine'

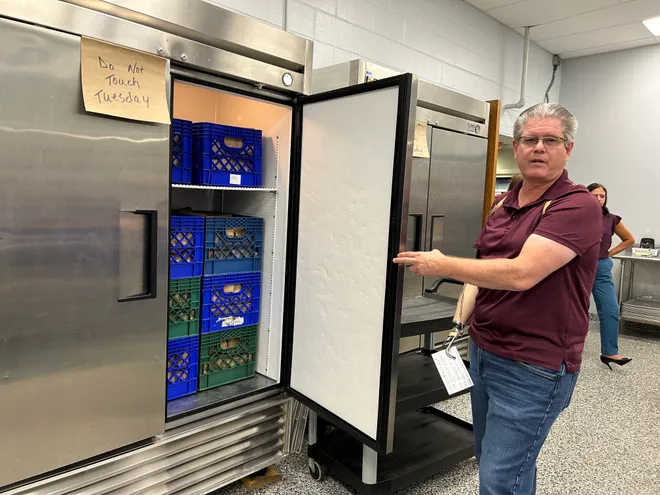

Ocean County Meals on Wheels has 1,115 people receiving delivered meals, executive director Jim Sigurdson said. Of those, 688 are older than 85 and most (1,085) are older than 75. About 12% of them are veterans; 70% of the recipients live alone. There are 82 people currently on Ocean County Meals on Wheels' waitlist.

Sigurdson isn't shy about expressing frustration that the organization can't help everyone who needs it. A quarter of the organization's $3,877,000 budget come from the federal government, but the rest comes from the state (2%), private donations (11%) and county coffers (62%).

Since 2019, the organization's costs have increased more than 28%, or about $10-$14 per meal.

"If you talk to people in real estate, they say, 'Location, location, location,'" Sigurdson said. "We say: Funding, funding, funding. It needs to keep pace with the rapidly growing senior population. It isn't."

Hollander said that a third of Meals' community-based groups, all public-private partnerships throughout the country, have waiting lists averaging three months or longer, hampered by funding shortfalls and a lack of volunteers.

Just 1% of Americans' philanthropy spending goes toward senior citizen-based causes, Hollander said. There are 2.5 million low-income seniors who are food insecure and not receiving meals.

Meanwhile, she said, the cost for Meals on Wheels to serve one senior for a year is the same as one day in a hospital or 10 days in a nursing home.

"Food is medicine," she said. "Nutrition is not just important for one’s physical health, but it also saves the taxpayers millions a year. Why wouldn’t we want to invest in an intervention that’s been working for over 50 years?"

'A moral imperative' in Pennsylvania

LuAnn Oatman is the CEO of the Berks County (Pennsylvania) Meals on Wheels and serves on the national organization's board. Berks County's seat, Reading, is urban and has a large Latino population. But outside the city, it's mostly suburban and rural with people of German, Irish, Polish, Pennsylvania Dutch and Italian descent.

"We have a little of everything," Oatman said. The program gears meals toward different tastes and recruits Black people and people of Latin descent to do outreach and deliver meals because, especially for older people, "like speaks to like," she said.

Berks County's Meals on Wheels serves about 1,200-1,300 people, adding 40 to 50 new people each month. Unlike Ocean County, which had to stop using volunteers during the pandemic and hasn't been able to start again, Berks has about 470 volunteers.

Berks County pairs some drivers with volunteers in programs such as Threshold who have autism and developmental disabilities. Oatman said that adds another volunteer to engage with seniors, and helps people in the programs find their own sense of purpose.

Unlike in densely populated New Jersey, Berks' population is more spread out, Oatman said: Some volunteers can drive 20 or 30 miles between deliveries; grocery stores might be miles and miles away and public transportation nearly nonexistent; and many of the area's older people aren't connected to the internet.

"We don’t make it easy on our seniors, that’s for sure," Oatman said. "We have a moral imperative to get food to the most vulnerable among us. Many of our folks dealing with one or two or more chronic diseases ... Many of our folks are not only homebound, they’re bed-bound."

'It's the social visit they look forward to'

That brings another function of Meals on Wheels into focus: Delivery drivers aren't just dropping a box on a porch or step. They call loved ones or families if the senior doesn't answer the door, or 911 in more dire situations.

Michael Zaccaria, a driver for Meals on Wheels in Ocean County, said he's formed bonds with the seniors he sees on his routes over the last two years. A former consultant and executive in the cosmetics industry, Zaccaria calls driving for Meals on Wheels "a feel-good job."

"There are people who look desperately forward to our visits," he said. "And their appreciation goes beyond words." Delivery drivers are on the lookout for signs of trouble: Is the house suddenly in disarray? Does the recipient seems confused, fatigued, agitated or unsteady? Twice a year, Meals On Wheels outreach workers do assessments as well.

"Most clients tell us as much as they love the meal, it’s the social visit they look forward to," Hollander said. "And for families, it’s good to know there’s someone checking on loved ones, especially if they live far away.

"Especially during the pandemic, we found that loneliness and social isolation are absolutely devastating. We know the power of that knock, and that we're delivering care, hope and joy to someone."

Contact Phaedra Trethan by email at ptrethan@usatoday.com, on X (formerly Twitter) @wordsbyphaedra, or on Threads @by_phaedra

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.