SpaceX launch: Europe's Hera spacecraft on way to study asteroid Dimorphos

A European spacecraft is soaring on its way to get an up-close look at the remnants of an asteroid that NASA deliberately crashed its own vehicle into two years ago.

Hera, an orbiter built by the European Space Agency, launched at 10:52 a.m. ET Monday from Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Florida. Ahead of the small craft is a two-year journey to Dimorphos, a tiny moonlet asteroid orbiting the larger 2,560-foot space rock Didymos.

The mission is part of a global effort between the world's space agencies to build a defense against dangerous space rocks that threaten our planet. In 2022, NASA intentionally slammed a spacecraft into Dimorphos at roughly 14,000 mph to test a method of redirecting asteroids hurtling toward Earth.

Dimorphos, which never posed any threat to Earth, still remains ripe for study two years later. Here's what to know about the Hera mission.

Hera spacecraft launches over Florida coast

Though Hurricane Milton is moving its way toward Florida's western coast, the Hera spacecraft still managed to depart Monday atop a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket.

That won't be the case for the launch NASA's Europa Clipper, which has been scrubbed until launch teams determine a new target liftoff date after the storm clears.

Forecasts on Sunday suggested only a 15% chance of favorable weather, yet ESA still confirmed conditions were “GO for launch” two hours before the scheduled liftoff time. The agency also provided a live broadcast of the event on YouTube.

Hera will now begin a two-year "cruise phase," the ESA said, which includes a close flyby of Mars within 4,000 miles of the Red Planet – closer than the orbits of the two Martian moons. The spacecraft is expected to enter the Didymos binary system's orbit in October 2026, according to the agency.

What is the Hera mission?

In September 2022, NASA demonstrated that it was possible to nudge an incoming asteroid out of harm's way by slamming a spacecraft into it as part of its Double Asteroid Redirection Test.

Launched in November 2021, DART traveled for more than 10 months before crashing into Dimorphos.

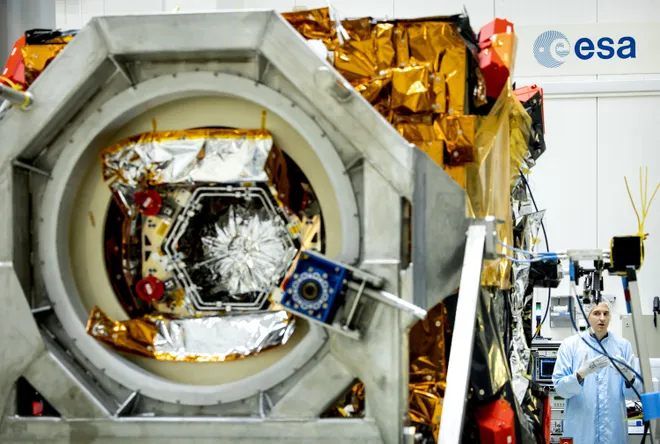

Armed with scientific instruments and two nanosatellites known as CubeSats, Hera is now on its way back to the region to understand not only how binary asteroid systems form, but to determine just how effective NASA's test was. Officials hope that by analyzing the results of NASA's experiment, space agencies will be better positioned to repeat the maneuver, particularly if an asteroid posing an actual threat is on a collision course with Earth.

Eric Lagatta covers breaking and trending news for USA TODAY. Reach him at elagatta@gannett.com

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.