'Mother Undercover:' How 4 women took matters into their own hands to get justice

When every parent's worst nightmare struck four mothers and their families, these women struck back. They didn't let any obstacles, including fear of threats, prison or death, stop them from getting justice.

For these mothers, even the risk of losing their life was not enough to deter them from harnessing all their power to do the right thing for their children.

An ABC News Studios four-part docuseries, "Mother Undercover," will chronicle four cases where mothers braved extreme dangers after experiencing murder, international kidnapping, corruption in the courts and one of the most deadly mass suicides in history.

The series, which premieres on Hulu on July 27, features these incredible moms telling their stories in their own words, alongside the people who helped them. "Mother Undercover," which includes archive footage and audio recordings from the incidents, also reveals how the four mothers are doing today.

Mom vs. killer

In April 2016, RJ Pantoja, 26, was brutally shot and killed outside a nightclub in North Philadelphia.

His mother, Lisa Espinosa, said she knew it was going to be an uphill battle to find her son's killer. More than half of the city's murders go unsolved and the no-snitch culture limited how much information she and investigators would get.

"In the back of my mind I’m thinking, 'RJ’s case is going to get forgotten if I don't stay involved,'" she said.

After RJ's brother showed her a video on social media revealing RJ and his friends getting into a fight before he was shot, Espinosa spent weeks tracking down anyone who was there or saw the killing.

She went as far as staking out some of RJ's friends and tried to get them to talk.

Espinosa was able to get some names of witnesses and got a few of them to talk and provide more information.

She handed her two weeks worth of discoveries to investigators.

"I knew that this was the last thing I can do for RJ," Espinosa said.

But that wasn't the end of her journey for justice, as Espinosa decided she wanted to send a message to the person responsible.

She got in touch with Helen Ubiñas, a columnist for The Philadelphia Inquirer and Daily News, and the paper interviewed Espinosa about her son's murder and her search for clues.

"I wanted the killer to know, 'I’m looking for you,'" Espinosa said.

In the meantime, Espinosa connected with community activists who gathered over the city's gun violence and they held major rallies over RJ's death.

She also began to spread 3,000 flyers across the neighborhood, including near the nightclub where her son was shot, seeking information from anyone who could help.

The extra attention brought more danger, as Espinosa said she and her family received death threats. But at the same time, she did get results.

Espinosa said she was messaged anonymously by someone who had information and claimed that RJ's killer hangs out at a bikers’ bar and his street name is Fax.

Ubiñas' article was published, five months after the murder, and soon after a new police detective asked for Espinosa's help and information.

A month later the police arrested and charged 30-year-old drug dealer Giovanny Perales with RJ's murder. Perales pleaded guilty and was sentenced to 18-24 years in prison.

Espinosa continues to be an advocate for families who have lost loved ones to gun violence and has pushed for more resources.

"So, in aiming to find RJ's murderer, a ripple effect happened," she said.

Mom vs. kidnapper

In August 2007, Tiffany Hotte's son Kobe was on a weekend trip with her former partner, Jeff, but neither returned home.

Months passed and there was no trace of Jeff or Kobe, who was 6 at the time, and Hotte would discover that Jeff took the boy to South Korea.

Although an international warrant was issued, investigators warned Hotte that it would be difficult to get her son back due to no extradition agreement between the U.S. and South Korea.

"My child was kidnapped, but I can't do anything to get him back," she said. "This was a mother's worst nightmare."

After starting an online campaign to raise awareness and get more information about her son, Hotte got an anonymous tip from someone in Seoul.

An English teacher at a Korean school said Kobe was her student and that Jeff was applying for Kobe to get Korean citizenship, which would make it harder for the boy to be brought back to the United States.

Despite warnings from the police that she could be arrested, Hotte decided to go to South Korea herself.

Hotte, who never traveled internationally, teamed up with Mark Miller of the American Association for Lost Children, a nonprofit that helps rescue kidnapped children. Together, they came up with a plan.

After meeting with the teacher, who provided a map of the school, Hotte, who is Black, went into the school wearing dark glasses, a cap, a mask and even whitening her hands to blend in.

"I knew that I was breaking the law by trying to kidnap a child," she said.

Hotte found Kobe in his classroom and fled to the U.S. Embassy. To facilitate the escape, she put the boy in a girl's wig and clothes.

But they were still not out of the woods. Even with assistance from the U.S. Embassy, Hotte, Miller and Kobe faced risking arrest at the airport.

After a long wait, they were able to board a plane and return to the U.S.

"Both of us were just very happy, like, thank you, we're out of here!" Hotte said.

Mom vs. corruption

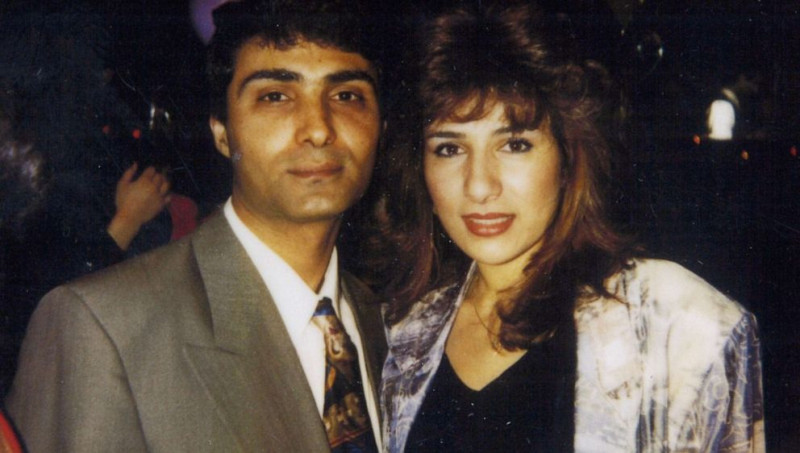

In 2002, Frieda Hanimov, a Russian Jewish immigrant, was going through a bitter divorce and custody battle with her estranged husband over their three children.

One day, officers knocked on her door and arrested her after allegations that Hanimov abused their eldest son, Yaniv.

"I thought that’s the end of my life," Hanimov, who was pregnant at the time, said.

Hanimov was released from a police precinct cell, but family court Judge Gerald Garson ordered that Yaniv stay with his father while the other two siblings remain with her.

Weeks of court visits yielded no change in the situation, but another man who was in Garson's court caught her eye.

Nissim Elmann, an electrical goods dealer, had gained custody of his kids and when Hanimov asked how he was able to do it, Elmann claimed he "had the judge in his pocket."

"He said ‘Yeah. I spent millions of dollars on this judge.’ Nice and clear with no hesitation," she recalled.

Elmann offered to give more help, but Frieda Hanimov said she was shocked. The next day she called the Brooklyn District Attorney's Office and told them about Elmann's claims.

The DA's office was interested in pursuing the case but they needed more hard evidence. Hanimov immediately accepted an offer to wear a wire and get Elmann on record.

"They gave me a recording device...They put it on my bag, so it's going to be clear so I don't miss anything," she said. "I said 'What the hell? I'm not losing anything. My kids, my kids, my kids.' That's the only thing I wanted to see, is my kids in my custody."

For seven months, Hanimov took part in several meetings with Elmann under the guidance of the DA's office and would pay thousands of dollars to get the judge to rule in her favor.

She and investigators would learn that Elmann served as a middleman and worked with a court appointee to represent her children, Paul Siminovsky, to facilitate the bribes.

Investigators were able to flip Siminovsky, and he wore a wire during a money transfer with Garson. The judge was eventually arrested on bribery charges.

"I was so happy, I feel like a big stone came out of my chest," Frieda Hanimov said.

Garson was convicted, suspended from the bench and sentenced to three to 10 years in prison on bribery charges.

No evidence of attempted bribery or any wrongdoing was found against Frieda Hanimov's husband . He faced no charges.

Frieda Hanimov eventually regained custody of Yuri.

Mom vs. cult

In the 1970s, Leslie Wagner-Wilson said she was taken in by Jim Jones' cult, the People's Temple, and became a devoted member.

It was there she met her husband Joe and had a son, Jakari. When Jones moved his cult out of California and to Jonestown, Guyana, Wagner-Wilson was at first reluctant to join her husband and son, but ultimately went with her family in 1978.

Wagner-Wilson soon discovered that Jones' idea of a safe community was just the opposite: rules separating kids and their families, verbal abuse, violence, suicide drills and the prevalence of weapons all started to weigh on her.

"Once I looked around I thought, 'Wait a minute,'" she said. "'Do I want Jakari to grow up like this? No. There’s no future in Jonestown for our babies, our children.'"

Wagner-Wilson intended to flee Guyana with her family and wrote a letter to her friend, a fellow member of the cult, about her intentions. The friend gave the letter to Jones, who forced Wagner-Wilson to be publicly shamed, attacked by members of her family in front of the cult.

"The whole audience is screaming, ‘You traitor,'" Wagner-Wilson recalled.

Wagner-Wilson was forced to work at a medical facility, cut off from her family. It was there she met a woman who worked in the pharmacy who told her that she and her boyfriend were part of a group that was looking to escape.

They had an opening on Nov. 17, 1978, when U.S. Rep. Leo Ryan took a two-day fact-finding mission with the press and concerned relatives of people who were members of the People's Temple. Jones and other leaders were distracted with the visit, and Wagner-Wilson said she decided to take her son with the group and leave.

"I begged them, 'If you see me shot dead, please get Jakari out,'" Wagner-Wilson recalled telling the group as they escaped under the guise of going to a picnic. "I was ready to die to make sure my son was free."

After making their way to a town, the group was confronted by police officers. The officers had heard about the atrocities at the camp and did not impose any harsh treatment, Wagner-Wilson said.

Back at the camp, Jones ordered his members to attack Ryan and his entourage after they kept investigating the camp. The congressman, three journalists and one cult member who tried to defect were killed.

Soon after the attack, Jones ordered the entire congregation of 918 followers, including 304 children, to drink cyanide-laced juice and commit suicide.

"I got Jakari out by the grace of God and a lot of help," Wagner-Wilson said. "There was so much joy. There was so much pain, and it lasted for years."

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.