James Larkin, Arizona executive who faced charges of aiding prostitution, dead at 74

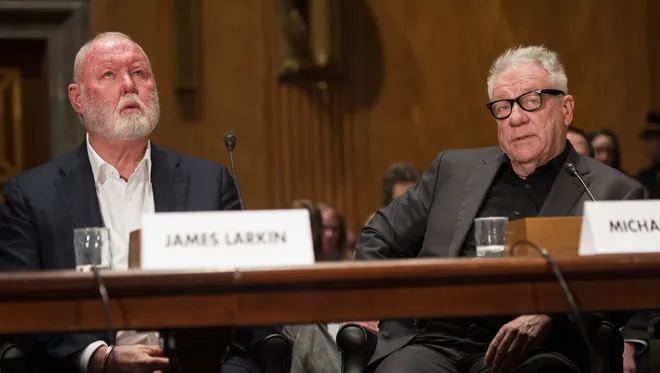

PHOENIX − James Larkin, who helped turn the Phoenix alternative weekly New Times into a chain that took over the venerated Village Voice in New York, died by apparent suicide Monday, days before a federal trial on charges he knowingly used online classified ads to facilitate prostitution.

He was 74.

The Superior Police Department in Arizona confirmed his death from a self-inflicted gunshot wound, which happened in the rural town an hour east of Phoenix. Larkin lived in Paradise Valley.

Larkin served as the business mastermind behind New Times, a free weekly newspaper that became known, under longtime editor Michael Lacey, for its hard-hitting exposes, arts coverage and irreverent style.

A life sentence for this child killer:Lori Vallow Daybell, whose children were murdered in 'evil' plot, sentenced to life

Adult service domination

Starting in 2010, Larkin and Lacey attracted notice not for their journalism, but for their classified advertising website, Backpage, that was dominated by advertisements for adult services. Law enforcement officials and anti-sex trafficking advocates argued the site hosted thinly disguised advertisements for prostitution.

The two men and their website evaded criminal charges and civil claims for years citing a provision of law that protected online publishers who posted words written by others.

But in 2017, a U.S. Senate subcommittee released a report containing emails, obtained under subpoena, that showed Backpage executives were not passively letting others use their site for escort ads. Rather, Backpage employees actively edited and moderated ads posted on the site. The report concluded that was done to allow prostitution activity to take place without making it obvious.

The next year, a grand jury returned a 93-count indictment against Larkin and Lacey. The April 2018 charges related to facilitating prostitution and money laundering. The FBI descended on both men’s homes. The Backpage website was shut down, displaying a notice that it was seized by the U.S. Department of Justice.

Larkin and Lacey faced federal trial in 2021 in a proceeding that was set to see prosecutors call two former Backpage executives to testify that the website was essentially an online brothel. The website’s CEO, Carl Ferrer, had admitted that the website was designed to aid in facilitating prostitution. He had pleaded guilty in 2018 on behalf of both himself and the Backpage website.

But after a handful of days of testimony, U.S. District Judge Susan Brnovich declared a mistrial. She said prosecutors had gone too far in eliciting emotional testimony regarding child sex trafficking, rather than proving the facts in the indictment.

A retrial in the case was set to start Aug. 8 before Judge Diane Humetewa.

'Move on':Mother of former missing Arizona teen asks the public to move on in new video

Alternative weekly grows into national powerhouse

The New Times newspaper was started in 1970 by Lacey while a student at Arizona State University. It was a response to the shooting of student protesters of the Vietnam War by National Guard troops at Kent State University.

Lacey was joined the next year by Larkin, who managed the business side and would eventually take the title of publisher.

The free weekly would grow into a chain that expanded nationally, swallowing up similar publications in Denver, Kansas City, Los Angeles and other cities. In 2006, it took over the Village Voice, cementing New Times' legacy as the nation’s premier publisher of alternative weeklies.

In 2008, Lacey and Larkin were arrested for an act of journalism. The then-sheriff of Maricopa County, Joe Arpaio, ordered the two men jailed for publishing, in full, a subpoena New Times received asking it for a slew of documents, including information on visitors to its website. Grand jury subpoenas are supposed to stay secret. But the New Times publicized it, calling it a breathtaking abuse of power.

Arpaio ordered the two men arrested in the middle of the night. But the misdemeanor charges were dropped the next day. A judge would declare the grand jury subpoena invalid. Maricopa County agreed to pay $3.75 million to Lacey and Larkin to settle the matter.

Lacey and Larkin were celebrated in journalism circles as defenders of press freedom.

Controversy over Backpage grows

But over the ensuing years, the two would increasingly be pilloried for allegations of profiting off the sex trade.

The back page of the New Times printed tabloid featured classified ads sold as a premium. The page was called the Back Page.

In 2004, Ferrer suggested that Lacey and Larkin move the classified ads online, adopting the moniker Backpage.com, court documents say. At the time, the website Craigslist.com was showing how much money could come through hosting the types of classified ads that had brought so much revenue to newspapers for decades.

Craigslist, though, soon became known to authorities more for its adult advertising than for its furniture or auto ads. In 2010, under pressure from law enforcement and anti-trafficking advocates, Craigslist shut down its adult section.

In an email quoted in the federal indictment, Larkin wrote that Backpage should prepare for a “deluge of adult content ads.” Larkin, in the email, referenced some of the strip club, escort and massage ads that long appeared in the print tabloids. Such adult advertising was “like it or not, in our DNA," he wrote.

As Backpage faced scrutiny from advocates, it would point to glowing emails from law enforcement, thanking it for helping to investigate suspected underage girls sold on its site.

Still, some who claimed they were trafficked on the site sought civil penalties. Some prosecutors, including then-California Attorney General Kamala Harris, sought criminal charges. Harris was elected vice president under President Joe Biden in 2020.

Lacey and Larkin fended off potential civil penalties and criminal charges under the shield of a federal law called the Communications Decency Act. It was intended to allow websites to delete offensive content without taking responsibility for everything on their site. It also allowed them to escape liability for words created completely by outsiders.

Backpage, according to federal prosecutors, raked in cash as it soon was dominated by adult advertising. Backpage charged users to post the ads, which, it said, was a request from law enforcement so users could be tracked.

Sale of New Times, focus on Backpage and code words

In 2012, as Backpage faced the same pressures that led to Craigslist taking down its adult section, Lacey and Larkin decided to separate it from New Times. The issues surrounding Backpage were a distraction from the business of publishing journalism, the two wrote in an email to staff. Lacey and Larkin sold the tabloids to a group of employees and held on to Backpage.

According to the indictment, Backpage made $112 million in 2013 and more than $134 million in 2014.

When authorities charged Larkin, they also looked to seize assets they claimed came from illegal transactions. Among the properties was an apartment in Paris.

Employees of Backpage told investigators with the U.S. Senate that it was common knowledge that prostitution was conducted on the website. One employee told Senate investigators that efforts to moderate ads amounted to putting “lipstick on a pig.”

Lists of code words were created and managers debated what was allowed and what tipped too far to spoil the ruse.

Users could post price lists, so long as they avoided specific, and brief, time periods, the emails showed. There were detailed guidelines about what level of nudity could be shown.

The internal emails showed that ads would receive more scrutiny depending on the amount of political heat or media coverage.

In a 2011 email, Larkin cautioned Ferrer that the moderation practices could eventually go public. “We need to stay away from the very idea of ‘editing’ the posts, as you know,” Larkin wrote.

'This is about speech'

In a 2018 interview with Reason magazine, Larkin said that Backpage was targeted because of the journalism the New Times published. He specifically cited reporting on U.S. Sen. John McCain, whose wife, Cindy McCain, had taken up the cause of ending child trafficking.

"We've never, ever broken the law," Larkin told Reason. "Never have, never wanted to.”

Larkin said that he was fighting the charges, at great financial peril, not to defend the rights of sex workers, but to defend a free press.

“I know this is probably heresy,” he said. “This isn't about sex work to me. This is about speech."

If you or someone you know may be struggling with suicidal thoughts, dial 988 to reach someone with the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline. They're available 24 hours a day and provide services in multiple languages.

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.