Florida's coral reef is in danger. Scientists say rescued corals may aid recovery

Crazy warm ocean temperatures continue to wreak havoc among coral reefs in Florida and the Caribbean this summer, bleaching and killing corals and spawning urgent rescue operations.

“After the hottest July on record, many northern hemisphere coral reefs – in Belize, Florida, Cuba, Mexico, along the Pacific coast of central America – have already experienced very high levels of heat stress, enough to trigger mass coral bleaching,” said international coral scientist Terry Hughes, a professor at James Cook University in Australia.

Despite the grave concerns, some scientists and non-profits say they are optimistic that advances in the ability to grow corals in laboratories and nurseries could help restore the reefs.

“There is much more than hope that we are going to be able to restore these coral reefs, and that we are going to be able to restore them with more resilient genotypes of coral,” said Michael Crosby, president and CEO of Mote Marine Laboratory and Aquarium.

Among the most diverse ecosystems on Earth, coral reefs are important to ocean health and to local economies, generating millions in fishing and tourism.

Ultimately however, Hughes and others said the only way the reefs will survive is if the world can address the rising greenhouse gas emissions that are the root cause of the heat plaguing the world’s oceans.

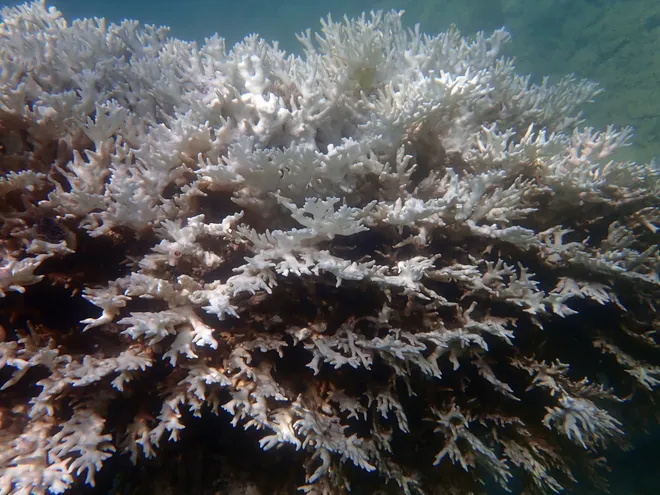

Dying coral

Snorkeling the coral reefs off the Florida Keys in the 1960s and 1970s was like swimming through a kaleidoscope, with colorful algae living among roughly 30 coral species covering the reefs, home to a rich diversity of marine life.

Within decades, polluted and warmer water had bleached and killed up to 95% of the corals, said Bill Precht, a Miami-based coral scientist with the environmental consulting firm Dial Cordy and Associates.

Now scientists fear this summer's unprecedented heat could deal a potentially fatal blow to the remaining coral – sparsely populated along the patchy reef that stretches from the Florida Keys to Palm Beach.

The current situation is grim, Precht said.

- Some observation stations near the Keys experienced some of the highest ocean water temperatures ever recorded in July and temperatures at several stations in the region have averaged 90 degrees or above since July 1.

- Abnormally warm ocean heat waves continue and could last into October or beyond.

- Scientists report some reefs already have seen nearly 100% die off.

When Lauren Toth checked one reef during visits just a week apart, the coral research scientist with the U.S. Geological Survey found everything turned "just stark white.”

“Almost 100% of these corals had lost all of their color, which really just speaks to how extreme that stress is," Toth said. Despite massive degradation seen at other times in her career, she said the bleached coral this summer is "unprecedented."

Few scientists are surprised. They say recurring marine heat waves and coral bleaching events are “exactly” what coral and climate scientists have predicted would happen.

What is coral bleaching?

Dozens of types of algae live inside corals in a mutually beneficial relationship that gives the corals color, nutrition and slight changes in water composition that help make its limestone skeleton.

When the water warms up to two degrees above normal average temperatures and remains there for 10 days or more, toxins begin to disrupt the algae’s photosynthesis process, Toth said. The coral then ejects the algae, trying to save itself. That spurs "bleaching," and without the essential algae, the coral starts to die.

Limited bleaching can happen in any given summer, but it typically starts around the end of August or early September, then the waters begin to cool and the corals survive, Toth said.

This year, NOAA satellites began tracking an unusual rise in ocean temperatures in the waters around Florida and the Caribbean in April. Bleaching started by mid-July, Toth said. “So rather than just being in a sauna for a couple weeks and then having a chance to cool down, (the corals) are sitting in that bathtub of hot water for probably over two months.”

Searching for a cure

Mote researchers are among many scientists working with state and federal agencies to improve ways of growing coral and repopulating reef skeletons.

“The coral reef in Florida, especially in the Keys, is simply not able to self replicate and keep one step ahead of the changing environment,” Crosby said. “We are basically watching these reefs slip into functional extinction."

Through its international coral gene bank, Mote is using genetics to find out what’s killing the coral, identify species that might be more resilient than others to heat and other stressors, and bring coral skeletons back to life, Crosby said. "Ten years ago, the existing paradigm in coral restoration science was you can’t do this."

Several universities in Florida are among those researching how to rehabilitate and grow coral in offshore nurseries, aquariums and tanks.

Corals also are growing in tanks and aquariums as far from the ocean as Ohio and New Mexico, as part of an Association of Zoos and Aquariums project to protect the genetic survival of corals in the Atlantic and Pacific oceans and buffer corals against climate change, stony coral tissue loss disease and other threats.

When the heat spiked this summer, it spawned massive coral rescue operations.

Racing to rescue

"There have been Herculean efforts to try to rescue some of the coral that's most at risk," said Ben Kirtman, an atmospheric sciences professor at the University of Miami's Rosenstiel School of Marine, Atmospheric, and Earth Science.

More than a half dozen research organizations, universities and government agencies launched emergency efforts to salvage fragments of rare and threatened corals they're growing in manmade coral nurseries off the Florida Keys, rushing them to deeper water and land-based laboratories. The groups included Mote, the Keys Marine Lab, the University of South Florida and the Coral Restoration Foundation.

Working in bathtub-like water temperatures offshore, they filled crates and trays with coral fragments grown in the research nurseries and brought them back to shore by boat, then delivered them to tanks and aquariums.

Mote worked with a variety of research partners, businesses and volunteers, to round up boats, trucks and people, Crosby said. “We implemented the largest scale evacuation of coral in a very short amount of time, literally in a matter of days, to try to salvage or save the very stressed and dying coral that were in our coral nurseries offshore."

They're seeing some initial success in some coral plantings that remain offshore, he said, demonstrating that some species growing in the nurseries are more resistant to heat than others.

Researchers will care for and monitor the rescued coral fragments until cooler waters return and the corals can be safely returned to the sea. But, with a brewing El Niño, no one knows when that might be.

What's causing the warmer water?

July was the globe's hottest month on record. The Gulf of Mexico, like much of the southern part of the country, has sweltered under a high pressure system this summer, which helped drive up water temperatures off South Florida.

Marine heat waves have spread across more than 40% of the world’s oceans, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Among the potential influences that experts said may be contributing to the ocean heat this summer, are:

- Natural cycles in ocean currents.

- Global climate change driven by rising fossil fuel emissions.

- Initial impacts from the El Niño in the Pacific.

- Cleaner air over the ocean after new regulations required a reduction in sulphur in shipping fuels.

- A temporary shot of water vapor in the Earth's stratosphere from the eruption of the Hunga Tonga volcano last year.

Warm water isn't the only threat to corals. Stony coral issue loss disease, first reported off Florida in 2014, has spread rapidly through the Caribbean, NOAA said. It's now found on reefs in 18 countries and territories, in at least 20 stony coral species.

A group of organizations including Sea World, NOAA Fisheries and the Fish & Wildlife Foundation of Florida partnered on the Florida Coral Rescue Center to try to stem its spread.

Great Barrier Reef could face similar heat within months

Six widespread coral-bleaching events have taken place on the Great Barrier Reef since 1998. Last year, for the first time, bleaching occurred during rainy and cooler La Nina conditions, even while some corals were gaining ground. Although it’s winter there, water temperatures are warmer than normal, already raising fears about the transition to summer.

The outlook for El Niño projects warmer water temperatures could persist into 2024 and be devastating to the reef off Northeast Australia, Hughes said. “We’re very concerned about a likely return of severe bleaching in 6 month’s time, as a new El Nino develops. It could well be the worst we’ve seen yet.”

The worst coral bleaching on record occurred during the El Niño of 2014-2017. Coral scientists are watching and waiting to see how this new El Niño will measure up.

There's way more tiny life on Earth than scientists had thought, study of coral reefs finds

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.