An eye in the sky nabbed escaped murderer Danelo Cavalcante. It's sure to be used more in US

In the middle of the night, a fixed-wing aircraft flew over rural Pennsylvania and detected a blip: it was one of America’s most wanted men wading through the dark.

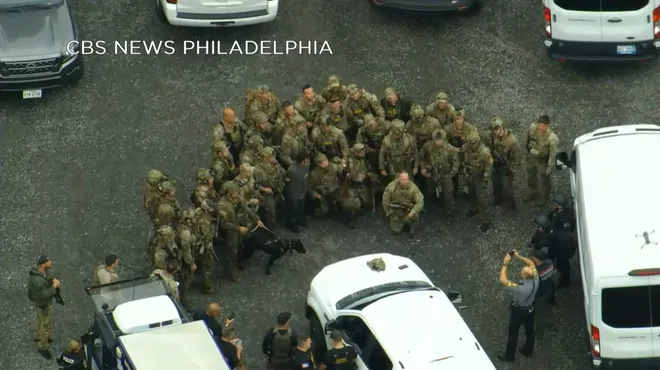

A multiagency task force of cops and federal agents searched frightened communities around suburban Philadelphia for nearly two weeks, looking for Danelo Cavalcante, a convicted murderer who escaped Chester County Prison at the end of August. Cavalcante, considered desperate and dangerous, evaded hundreds of officers, helicopters, drones and dogs.

But in the wee hours on Wednesday, there was one thing he couldn’t run from: his own heat signature.

The method police used to spot Cavalcante is called thermal imaging, which 60 years ago was an emerging technology mostly reserved for the military. The technology has come a long way in terms of affordability and is becoming more of a mainstay in American life. Along the way, its use has conjured concerns it could violate the Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, which protects Americans from unreasonable searches and seizures.

Pennsylvania State Police deployed use of the technology from the beginning of their search until the man was captured without a warrant, said Lt. Adam Reed, a spokesperson for Pennsylvania State Police. A warrant wasn’t required in the case because the heat imaging was not pointed at a building.

How does thermal imaging work?

While human eyes and cell phone cameras see using visible light from the sun or artificial bulbs, thermal imaging detects thermal energy.

While not visible to the human eye, virtually everything emits some level of thermal energy, even ice, said Bill Parrish, co-founder and chief technology officer of thermography company Seek Thermal.

The sensors measure an object’s heat signature and portray what is essentially its radiated heat on a screen, which can be as little as a handheld device or large enough to be mounted on an aircraft, said Joel Shults, municipal judge and retired Colorado police chief.

Adam Scott Wandt, a professor of public policy at John Jay College of Criminal Justice and expert in policing technology, said many police departments use the technology, especially in helicopters.

“These cameras are used constantly, 24/7,” he said. The technology once was exclusively used by military or police personnel, but today average Americans including electricians and firefighters can access them at the Apple store or on Amazon for a couple hundred dollars, he said.

“They’re extremely useful tools when using it to catch a suspect,” he said.

Pros and cons of thermal imaging

Even the most evasive fugitive virtually always has one giveaway: body heat. While camouflage gear and evasive maneuvers can hide a person from tactical teams and other technology, thermal imaging is harder to run from, Shults said.

Also, the technology works as a receiver, meaning it does not bear the risk of having a signal detected, as no signal is sent to retrieve heat information, he noted.

However, thermal imaging doesn’t come without its pitfalls. While people have unique heat signatures, it is difficult to recognize a specific person using a thermal camera, because the quality is much more pixelated than that of a cell phone camera.

“In other words, if somebody’s trying to hide in the bushes, this is a good technology for doing that,” Parrish said. But using thermal imaging to find someone in a crowd would be rather fruitless, he noted.

In Cavalcante’s case, the technology provided benefit since there was already a perimeter that officers were searching, based on previous information. The spot was also a rural, wooded area containing few people.

On the opposing side, the case has illuminated fourth amendment concerns.

A Supreme Court case, Kyllo v. United States, in 2001 challenged the use of thermal-imaging technology on private homes as a violation of the fourth amendment of the U.S. Constitution, which guarantees Americans protections from unreasonable searches and seizures. The court decided that use of the technology falls under “search” and that a search warrant is needed to use the technology on private property.

ESCAPED PRISONER CAPTURED:What Danelo Cavalcante told investigators about his plans

Wandt said in his mind, there were “no ethical issues” in this case.

“This is an extenuating circumstance,” he said. Cavalcante was found near a pile of logs near a tractor dealership.

“They weren’t using it to see if people were growing marijuana in their house, they were searching for something urgent: a state murderer,” said Wandt.

Where is thermal imaging headed?

“It’s like GPS if you think about where that was years and years ago before they started putting it in cell phones and everything else,” Parrish said.

Thermal imaging began in the 1960s as a military tool, Parrish said, with one unit costing around $1 million. Now, a gadget of similar quality small enough to plug into a cell phone can be bought for a couple hundred dollars.

Application has also expanded well past military use, Parrish noted.

“The technology has really developed dramatically over the years, and if you extrapolate where that’s heading, you can easily see these things being adapted into a lot of different applications,” Parrish said.

DISCARDED DNA:The controversial clue in the trash that's bringing serial killers to justice

He anticipates the biggest application will be in the automotive industry, where heat sensors can extend a driver’s visibility far past highlights to alert pedestrians or animals further down the road, especially in dark or foggy conditions. Right now, the technology is exclusive to higher end vehicles, but as with other technologies in the past, Parrish anticipates the cost will drop as it further develops.

Other uses outside of law enforcement and cars are also being explored. One such use could come to the kitchen, as heat sensors may be added to appliances like microwave ovens to detect when food is ready. It can also be applied to detect how much energy is leaking out of homes through windows.

The technology has also expanded into larger scale production, Parrish said, from just a few thousand sensors when it first began to several million in 2023.

“This cost of this stuff has come way down, and we’re beginning to see it as kind of a ubiquitous thing,” Parrish said.

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.