Her sister and nephew disappeared 21 years ago. Her tenacity got the case a new look.

VALDOSTA, Ga. – Mary Ramsbottom stood outside the gates of Martin Stadium on Friday night, surrounded by tailgaters and big boisterous families sporting face paint and custom outfits in the red and white colors of Lowndes High School. She had driven four hours from her home near Orlando to make sure she was there on time.

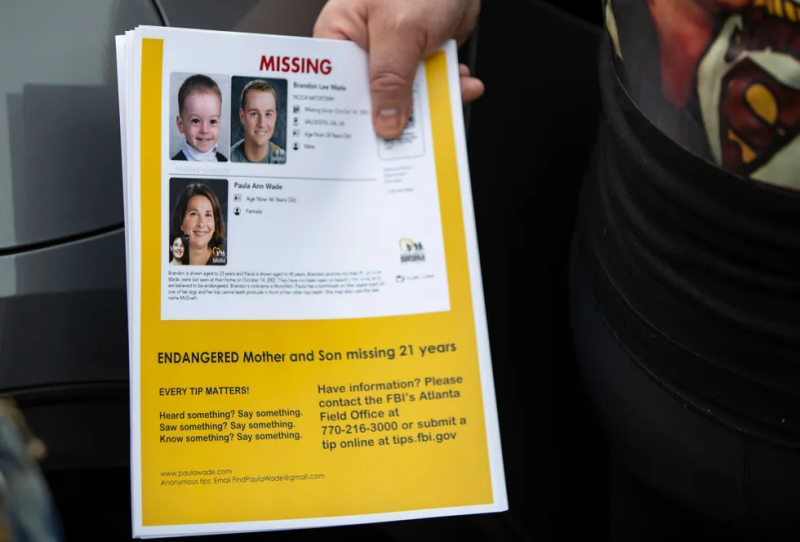

Only Ramsbottom, 58, wasn’t outside the 12,000-seat “concrete palace” awaiting the Vikings' homecoming game. She had another tradition to uphold. Gripping a stack of yellow flyers, she pressed the paper into the hands of dozens in line for tickets.

“Can you please take this and share it on your social media or with your friends and family?” Ramsbottom implored grandparents and teenagers streaming toward the entrance. “We just need the right eyes to see this.”

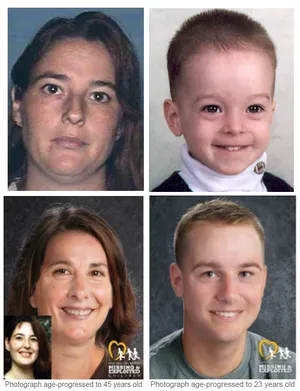

The flyer featured the last clear photographs taken of her sister and nephew. Next to the pictures were manufactured images artificially aging them both. Underneath bold letters said, “ENDANGERED Mother and Son missing 21 years.”

For two decades Ramsbottom and her family have traveled to Valdosta, a small south Georgia city just north of the Florida state line. They come to commemorate Oct. 14, 2002, the day Paula and Brandon Wade were reported missing. Paula was 25 and her boy was 3.

Paula, a manager at Sam’s Club, didn’t show up for work that day, the first day she had missed in five years. A search of her apartment found neither mother nor child, only Paula’s car keys, wallet, purse and glasses, without which she was nearly blind. The only thing missing was Brandon’s car seat.

Investigators scoured the apartment complex but found no signs of foul play. Detectives questioned people of interest, including Paula’s estranged husband, who was in the military and had moved out of state, but none of the interviews led anywhere. No one has been named a suspect or arrested in connection with Paula and Brandon's disappearance.

Other agencies offered help, but the case was cold from the very beginning.

“It was an immediate dead end and it’s stayed like that since,” Ramsbottom said. “We know as much now as we did when they first went missing.”

But Paula’s family never gave up. Along with the annual Valdosta pilgrimage to keep up interest in the case, Ramsbottom has spent her evenings on John and Jane Doe websites, spreading the word on true crime social media pages and hounding the local police department for new information.

The decadeslong effort paid off in August, when the FBI and the Valdosta Police Department announced “a new push to find answers.”

For the first time, the federal agency placed Paula and Brandon on its public missing persons list with images of what they might look like today. The Valdosta Police Department assigned a new detective to the case to reexamine evidence and search for new leads.

“As of this time all leads and clues have been exhausted,” Stephen Thompson, commander of the Valdosta Police Department’s bureau of investigations, told USA TODAY. “A fresh pair of eyes, new thoughts, ideas, and hopefully fresh leads could be the break needed.”

On Friday night, as the football game began, Ramsbottom and her 32-year-old daughter, Tara, quietly walked the sprawling, empty parking lot with their rat-terrier mix, Shamus, slapping flyers against windshields.

When the crowd roared for the night’s first big play, Ramsbottom stopped and looked out at the packed stands.

“Brandon would have played ball if this all hadn’t happened,” she said.

The many missing

On any given day in the United States, there are about 90,000 active missing-persons cases, according to the Department of Justice. And while most are found soon after they’re reported missing, tens of thousands remain unsolved for more than a year, the benchmark many agencies consider a cold case.

The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children is working 7,000 active cases – 3,000 of which involve a child who has been gone for more than a year, said Callahan Walsh, an executive director for the center. Some of their oldest cases date back to the 1960s, but most are from the past several years.

The search for missing persons can stretch for years or decades. In some cases, the missing outlive the loved ones pursuing answers.

The most important tool in the recovery of missing children, Walsh said, is the dissemination of their image.

“All it takes is one person to see that picture and spark recognition,” he said. “But it has to be the right person.”

The national center routinely creates age progression photos, even when cases are decades old, to keep the images circulating.

“We've seen way too many long-term recoveries to ever give up hope on any of the missing children that we're searching for,” Walsh said. “We know the families won't give up hope, and we won't give up hope either.”

The mystery

Paula Wade grew up in a military family. Her father was in the Air Force, and she and her sister, Mary, and brother, Regis McGrath, spent most of their childhood and adolescence in Europe, where their father was stationed.

Mary was always protective of Paula, who was 12 years younger. During Paula's teen years, the pair bonded over music.

“I was like … the cool big sister,” Ramsbottom said. "She liked whatever I was listening to."

Paula married her high school boyfriend soon after graduation. They had met in Germany, Ramsbottom said. Paula's husband, who was in the military, was sent to Korea for a year after the marriage, and Paula went to live with her older sister. The couple moved to Valdosta together when he returned. A few years later Brandon was born. Paula called him "Munchkin."

After a few years, Paula’s husband was transferred to Shaw Air Force Base in South Carolina. While he searched for a place suitable for his family, Paula struggled to pay the bills in Valdosta, and the couple grew apart.

When Paula’s boss offered her a position at a new Sam’s Club opening in Kissimmee, Florida, near her parents, she started packing. Her father made plans to drive up and help with the move.

A week later, Paula and Brandon were gone.

“We were talking just days beforehand about how excited we were,” Ramsbottom said. “I’d just moved back to Orlando with my kids, and with her job transfer, the kids were going to grow up together.”

An ‘ambiguous loss’

Oct. 14, 2002, separates what Ramsbottom calls the “before and after.”

The first weeks and months after that day were enveloped in the search for Paula and Brandon. But over time, Ramsbottom had to manage her own life. “You need to pay the bills and take care of your own kids,” she said. “You just have to find time for everything.”

For years, Ramsbottom would get home from work, spend time with her kids, then start her “second job” – looking for her sister and nephew. She became a fixture on websites for missing people and social media pages. Each year, she joined her parents on the fruitless mid-October journey to Valdosta.

Over the years, there were glimmers of hope.

In April 2003, Brandon’s was the first missing-child photo displayed on the golf bag of pro golfer Briny Baird, raising awareness for the cause of unsolved cases of missing children.

In 2005, Paula’s brother, named Regis after his father, entered an Iron Man competition in honor of his sister and nephew and raised more than $16,000 for missing kids.

“We’ve done all kinds of things to keep this case in front of people,” Ramsbottom said.

The last trip to Valdosta that included the whole family was in 2010, the eighth anniversary of Paula and Brandon’s disappearance. Ramsbottom and her parents stood in front of local reporters and urged people to call a tip line if they knew anything about what happened to Paula.

No tips came.

The following year, their father, a Vietnam veteran who had been exposed to Agent Orange, died. Five months ago, their mother died after being diagnosed with an aggressive form of breast cancer.

“They went so long without answers and never gave up hope,” Ramsbottom said. “They died with that ambiguous loss that we all still feel. That breaks my heart.”

A parking lot connection

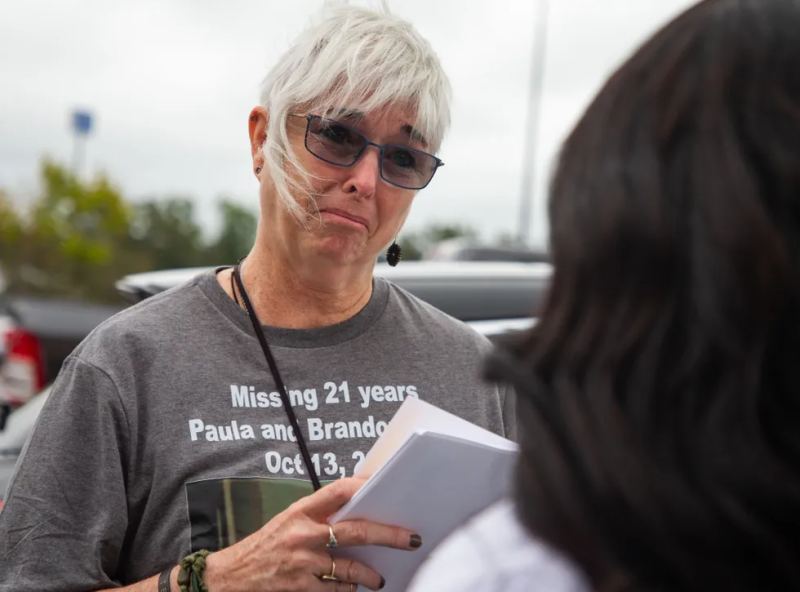

Ramsbottom and her daughter spent Saturday handing out flyers in the parking lot of the Sam’s Club where Paula worked and was last seen.

After hours in the afternoon heat, Ramsbottom stood near the store entrance scanning for parked cars without the paper tucked under windshield wipers. Then someone tapped her on the shoulder.

“I used to work with Paula,” said Maria Manning, 55, sporting a Sam’s Club vest. “Paula actually promoted me.”

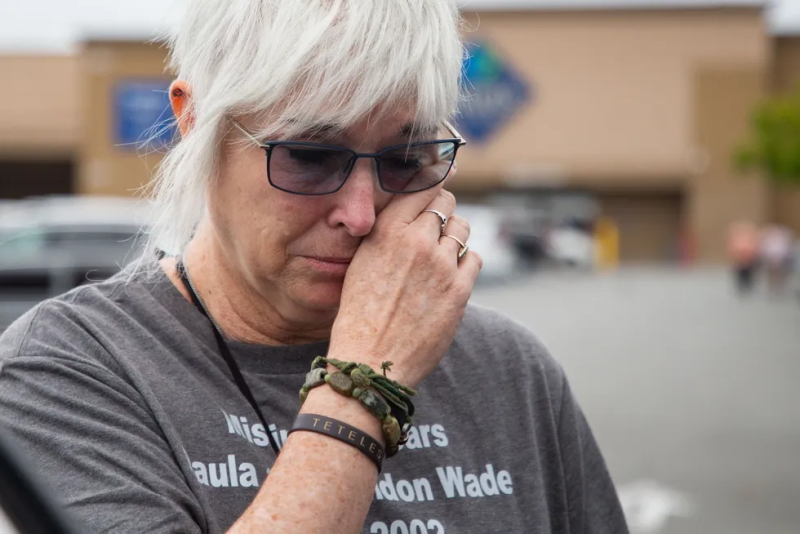

Ramsbottom’s lips trembled and her eyes filled with tears.

Manning was a cashier when she met Paula, who offered her a job on the membership team she was leading. The women lived at the same apartment complex, and after Manning took the promotion, Paula gave her rides to work.

Manning has kept up with the case and often thinks about Paula and “her Munchkin,” she told Ramsbottom.

“God bless you for still being out here looking for them,” said Manning, now an assistant store manager.

As shoppers maneuvered carts and lugged grocery bags around them, the women embraced.

“I have no other option,” Ramsbottom said. “That’s my baby sister.”

To report a tip in the case of Paula and Brandon Wade, contact the FBI's Atlanta Field Office at (770) 216-3000 or submit one online at tips.fbi.gov.

Contact Christopher Cann by email at ccann@usatoday.com or follow him on X @ChrisCannFL.

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.