Paramedics who gave Elijah McClain ketamine face jury selection in 'unprecedented' trial

Jury selection is expected to begin Monday in the rare trial of two paramedics charged in the 2019 death of Elijah McClain as the legal battle over the Colorado case comes to a close.

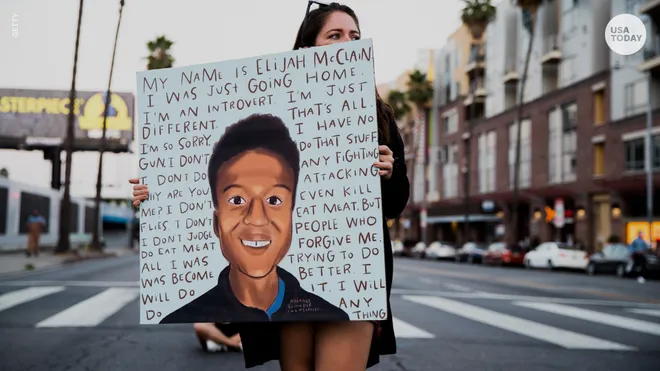

McClain, a 23-year-old massage therapist, died due to "complications of ketamine administration following forcible restraint" after he was stopped by Aurora police and injected with the powerful sedative by paramedics, according to an amended autopsy report released last year. McClain's death, which gained renewed attention following the 2020 murder of George Floyd, sparked protests and national concern over the use of sedatives during police encounters.

During two previous criminal trials this fall, defense attorneys for the officers involved in the stop repeatedly blamed McClain's death on the ketamine, not the physical restraint. Paramedics Jeremy Cooper and Lt. Peter Cichuniec with the Aurora Fire Department will stand trial on charges of manslaughter, negligent homicide and several counts of assault. Cooper and Cichuniec have pleaded not guilty and attorneys for the pair did not immediately respond to a request for comment from USA TODAY.

It is rare for police officers to be charged or convicted in on-duty killings, and experts say it is even rarer for paramedics to be criminally prosecuted in cases like this.

"The prosecution is in completely uncharted territory on this," said Ed Obayashi, an attorney and expert on police use of force. "Based on what I've seen, this is unprecedented."

Prosecution of paramedics is 'unique and unprecedented'

Medical workers in other states have been charged in deaths involving law enforcement. Paramedics in Illinois are facing first-degree murder charges after a patient they strapped facedown to a stretcher suffocated, and a nurse in California who drew blood from an unresponsive, handcuffed patient as officers pinned him down was charged with involuntary manslaughter, the Associated Press reported.

But Douglas Wolfberg, a founding partner of a law firm which represents emergency medical service workers, said cases like McClain's are typically handled in the civil court system through medical malpractice litigation. He said prosecutors in Colorado are instead "criminalizing deviations from medical protocols and errors in medical judgment, and that's what makes the theory of prosecution unique and unprecedented." Wolfberg said he believes it is unlikely the paramedics will be convicted.

"I feel like the prosecution has a steep hill to climb," he said.

Kenneth Udoibok, a lawyer representing a paramedic who in a whistleblower lawsuit alleged police in Minnesota pressured him to administer ketamine during an arrest, said it is often difficult to hold police or paramedics civilly or criminally liable in these cases due in part to qualified immunity. Udoibok said he hopes prosecutors will be able to secure a conviction in the McClain case, but said success is "a real long shot."

Obayashi agreed a conviction is unlikely, calling the case an example of "prosecutorial overreach."

"The message it sends is extremely dangerous to law enforcement, the paramedic community and especially the patient themselves," he said. "Because it's one thing for a cop to second guess his or her actions, which we don't want, but do we want to place first responders in that same situation where they are going to second guess?"

Prosecution raised awareness, but more legislative changes needed

The trial comes as the medical community has begun rejecting excited delirium as a diagnosis and recognizing that ketamine has a high rate of respiratory complications, according to Paul Appelbaum, director of the Center for Law, Ethics, and Psychiatry at Columbia University's College of Physicians & Surgeons.

In 2021, Colorado's governor signed a law prompted by McClain's death prohibiting law enforcement from directing medical professionals to administer ketamine and barring medical providers from using ketamine to subdue a suspect unless there is a justifiable medical emergency.

Udoibok said he believes more states should create similar legislation. Wolfberg warned such legislation should not only focus on ketamine - which is just one of the many drugs paramedics have at their disposal - but rather the broader issue of paramedics administering drugs during encounters with law enforcement.

Appelbaum declined to speculate on whether a conviction in the McClain case is likely, but said the charges may have already had a positive impact.

"The prosecution itself has undoubtedly made paramedics around the country aware of the dangers simply of using ketamine and the dangers of acquiescing to police requests to use ketamine," Appelbaum said. "Will the conviction make a difference in that regard? I think it may be that the important step, the important impact has already occurred."

Why was Elijah McClain injected with ketamine?

McClain was walking home from a store on Aug. 24, 2019 when he was stopped by police and violently restrained. He was not armed or accused of committing a crime, but a 911 caller reported a man who seemed “sketchy.”

Three officers quickly pinned McClain to the ground and placed him in a since-banned carotid artery chokehold. According to the indictment, Cooper and Cichuniec concluded McClain was suffering from a disputed condition known as "excited delirium," which is not recognized by many major medical groups and has been associated with racial bias against Black men, about two minutes after arriving on scene. Cooper then injected McClain with 500 milligrams of ketamine, which is more than the amount recommended for his weight, the indictment said.

The indictment said the diagnosis was inaccurate and the administration of ketamine was unlawful. Prosecutors have argued police encouraged the paramedics to give McClain the sedative by saying he had symptoms, like having increased strength, that are associated with excited delirium. Defense attorneys indicated they plan to blame police for McClain’s death, the Associated Press reported.

What is excited delirium?Advocates say excited delirium provides cover for police violence. They want it banned

Is it legal to give someone ketamine during an arrest?

In medical settings, ketamine is routinely used for its rapid and anesthetic effects. Medical and legal experts have previously told USA TODAY that giving an appropriate dose of ketamine in otherwise healthy patients following proper medical judgements is generally considered safe and legal.

But McClain's death and reports that the drug is being used more often in situations involving law enforcement have sparked concerns, including that police can influence a paramedic's decision to administer sedatives. The American Society of Anesthesiologists has said in a statement it "firmly opposes the use of ketamine or any other sedative/hypnotic agent to chemically incapacitate someone for a law enforcement purpose and not for a legitimate medical reason."

A 2021 investigation in Colorado found Aurora Fire had a consistent pattern of illegally administering ketamine. Records from January 2019 to June 2020 show the department reported administering ketamine 22 times for excited delirium, and in more than half the incidents, paramedics administered more than the maximum allowable dose for the reported weight of the patient and failed to follow monitoring protocols.

Police officers in Minneapolis repeatedly requested first responders sedate people with ketamine, according to a draft of a city report obtained by the Star Tribune in 2018. On multiple occasions, people who were suspected of committing crimes or already appeared to be restrained suffered heart or breathing failure due to the drug, the outlet reported.

"No clinical provider, physician, nurse, paramedic, or otherwise should ever administer a drug or perform any procedure just to assist law enforcement with apprehension or detention or interrogation or anything," said Wolfberg. "It should only be based on the clinical circumstances presented to the to the healthcare provider."

Contributing: Claire Thornton, Christine Fernando and Ryan Miller, USA TODAY; The Associated Press

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.