Not just the Supreme Court: Ethics troubles plague state high courts, too

This story was published in partnership with theCenter for Public Integrity, a newsroom that investigates inequality.

Since 2015, a North Carolina Supreme Court justice has heard at least six cases involving the massive utility Duke Energy, a company in which he and his wife had a direct financial stake.

In each of the cases, Paul Newby — chief justice since 2021 — sided with the utility. North Carolina’s Code of Judicial Conduct states that “a judge should disqualify himself/herself in a proceeding in which the judge’s impartiality may reasonably be questioned,” including when they or a family member have “a financial interest in the subject matter in controversy or in a party to the proceeding.”

Newby did not respond to emails and calls to the judicial branch and his chambers requesting an interview. He also did not respond to a detailed list of questions from the Center for Public Integrity about his stock ownership and approach to judicial ethics.

“This is a big deal. This does not look good,” said Gabe Roth of Fix the Court, which advocates for judicial transparency. “Owning even one share of stock brings in that doubt that the judge might be biased.”

Newby and his wife said in a 2023 disclosure form that they owned at least $20,000 in Duke Energy stock, and one or both owned stock while each of the six cases involving Duke and its subsidiaries was before the court.

It is against the law for federal judges to hear cases when they own stock in a party. But state supreme court justices, in North Carolina and elsewhere, are not held to the same standard.

Across the country, state high courts wield enormous power over abortion, LGBTQ+ rights and elections, among other issues. But judicial ethics at the state level receive scant attention. Experts say that’s a mistake and that potential problems are widespread.

Ethics issues can arise at several points in the judicial process. Many state high court justices make their own decisions about recusal, with virtually no opportunity for review. They often have a say in their own discipline. And in numerous states around the country, they disclose only meager and hard-to-access data about their finances.

The fact that Newby’s conflict has never been reported before underscores the limited public attention to judicial ethics at state courts.

Ethics scandals at the U.S. Supreme Court have dominated headlines in 2023, on the back of ProPublica’s blockbuster reporting about ethical lapses by Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito. The mere perception of bias can be harmful to public trust in courts, and the court’s approval rating has sunk to record lows.

Financial conflicts and ethical issues can also harm trust at the state level, where the vast majority of cases start and end. That’s compounded by an environment in which courts have become deeply politicized.

A Public Integrity investigation this year found that Republican politicians in eight states transformed their high courts by altering the size of the court or the process by which justices reach the bench. North Carolina’s switch to partisan elections and flip to Republican control earlier this year was among the starkest examples — the new Republican majority reheard a case decided just months earlier, and ruled that partisan gerrymandering was legal.

Yet, when judicial ethics are violated at state high courts, the public may never learn about it. While America’s state supreme court justices are some of the most powerful political actors in the country, they are also among the lowest profile.

“You’ve got 25,000 judicial officers in the United States, and a spotlight is not being shone on a lot of them,” said Indiana University law professor Charles Geyh. “There is misconduct by a lot of lower court judges that goes unnoticed and unreported, and undetected and unsanctioned.”

Geyh said systems of judicial discipline are poorly designed in many states. “When it comes to disciplinary activity, most state high courts are, to some extent, put in the position of foxes guarding their own hen houses,” Geyh said, with state supreme courts making decisions about potential misconduct by their own members.

State courts also deal with a factor completely absent at the federal level: judicial elections. A state supreme court race in Wisconsin this spring attracted a staggering $51 million in spending.

The mix of political money and justices campaigning like politicians is “a thermonuclear problem,” Geyh said. Campaign donors may end up in court before the very judges that they helped to elect.

“I hear people talking about these federal conflicts of interest. And it’s terrible,” said Billy Corriher of the People’s Policy Project, who has written widely about state high courts. “But what we’re seeing at the state level is just a whole different level of potential conflict of interest and corruption.”

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 2009 that “extraordinary” campaign spending by a party to a case could violate the due process rights of an opposing party, if a judge didn’t recuse.

A 2017 report addressed the “recusal quagmires” created by the river of money flowing into judicial elections. Only 16 states have recusal procedures for state high courts, the Institute for the Advancement of the American Legal System at the University of Denver found. And few states track data on how often judges actually recuse. The lack of hard numbers and scrutiny has meant that the landscape of recusal at high courts is unclear even to justices and scholars.

The report also cast doubt on the practice of allowing justices to make their own recusal decisions. “Substantial social science research on unconscious judicial bias establishes that judges, like most people, are overly confident in their ability to be impartial in potential conflict situations,” it said.

When researchers at the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law reviewed high court policies around recusal in 2016, they found that justices decide on their own recusal in 35 states. There’s no opportunity for review short of appealing to the U.S. Supreme Court.

North Carolina’s system grants individual justices tremendous leeway.

“It is the judge’s decision whether or not to recuse him or herself,” Wake Forest Law professor Ellen Murphy said. She pointed out that the state’s Code of Judicial Conduct says that judges can invest in mutual funds without raising concerns about potential conflicts, but that in owning stock, judges “have a duty to recognize that what that means is that the everyday citizen might reasonably question their impartiality.”

Recusal can begin by a motion of any party. Docket sheets for the six cases involving Duke Energy and its subsidiaries that Newby heard do not show the filing of any such motions. The code also makes clear that “nothing in this Canon shall preclude a judge from disqualifying himself/herself from participating in any proceeding upon the judge’s own initiative.”

Recusal and disqualification are distinct concepts, but the line between them can be blurry, and even legal experts discuss them interchangeably. North Carolina’s policy covers both.

Newby did not cast a deciding vote in any of the six cases, which concerned legal matters ranging from rate hikes to Duke Energy’s monopoly power.

But in a 2016 case, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that a Pennsylvania judge with a conflict tainted the judicial process, even without casting a deciding vote. “The fact that the interested judge’s vote was not dispositive may mean only that the judge was successful in persuading most members of the court to accept his or her position,” Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote.

Finances cloaked in secrecy

Recusal for financial conflicts is simple — for federal judges.

There, judges are required to recuse themselves in any case where they or a close family member own even a single share of stock in a company that’s a party. They are expected to avoid even the appearance of a conflict. A computer system automatically screens judges for such issues before assigning cases.

That makes it more difficult for judges to knowingly or accidentally hear cases in which they have a financial conflict.

The system isn’t perfect. The Wall Street Journal reported in 2021 that over 130 federal judges “violated U.S. law and judicial ethics by overseeing court cases involving companies in which they or their family owned stock.”

No one knows how many state justices are taking actions that would be barred under the federal system. But it’s clear that it does happen. In addition to Newby in North Carolina, members of the Louisiana and California supreme courts have each sat on cases involving parties in which they reported that they or their family owned stock.

In Louisiana, Fix the Court identified several cases that Louisiana Supreme Court Justice Scott Crichton presided over in 2018, 2019 and 2020. The lawsuits involved public companies in which he or his wife owned at least $5,000 in stock, among them ExxonMobil.

A response from the court’s general counsel stated that Louisiana’s Code of Civil Procedure does not compel a justice to recuse based on stock ownership, and added that “no litigant moved to recuse Crichton in these matters.” The response also noted that Crichton’s stock ownership is managed by an adviser who makes independent investment decisions, and that Crichton’s wife owns “some of these particular stocks.”

In 2021, California Supreme Court Justice Carol Corrigan granted a petition for review in a case involving the media company TEGNA; she reported owning between $10,000 and $100,000 in TEGNA stock that year. A television journalist working for the company’s Sacramento ABC affiliate had sued for public documents under California’s transparency law, and Corrigan and other justices sent the case back to lower court. The state Supreme Court later unanimously rejected a request by the government agency to “depublish” the lower court’s opinion in the case.

A spokesperson for California’s Judicial Council said that “due to clerical errors, the court’s internal case captioning and screening procedures did not identify a potential conflict, and Justice Corrigan was unaware of the company’s involvement in these matters. The court has since implemented an automated system in which potential conflicts are initially screened and identified by the court’s case management system.”

The American Bar Association’s Model Code of Judicial Conduct recommends judges disqualify themselves when they or a family member “has an economic interest in the subject matter in controversy or in a party to the proceeding.”

The U.S. Supreme Court only adopted an ethics code last month after the string of ethics scandals. The new code, like many state high court policies, allows the court to police its own ethics.

U.S. Supreme Court justices are still not subject to the financial conflict recusal policy covering other federal judges; they have at times heard cases in which they have a financial interest.

But the finances of many state supreme court justices, and their potential conflicts, are cloaked in greater secrecy than at the federal level.

A 2022 law now requires federal judges — including U.S. Supreme Court justices — to report stock transactions over $1,000 within 45 days. “It gives the public more information and a better sense of what potential entanglements exist,” said Fix the Court's Roth.

Roth said he was not aware of any state that required its high court judges to report stock transactions in a similar manner. He pointed to Texas as an example of the frustrating, uneven disclosure landscape. Texas’ disclosure forms “are great, but it’s a pain in the ass to get them,” since they are not available online, he said.

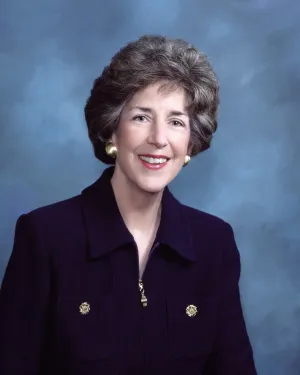

Texas has similar language about financial conflicts as North Carolina. Disclosures there show that, faced with similar circumstances as Newby’s, Texas Justice Debra Lehrmann made a different decision. She did not participate in a ruling issued this February in a case involving ExxonMobil. Lehrmann had reported owning between 100 and 499 shares of the company’s stock in her most recent disclosure.

Concern over financial entanglements at state supreme courts, and the lack of transparency about justices’ finances, are not new. A decade ago, Public Integrity gave 42 states failing grades for their level of transparency around judicial finances at state supreme courts.

In North Carolina, Public Integrity found that former justice Robert Edmunds “reported owning Duke Energy stock in 2012, yet he participated in a case involving the energy company that year.”

The story also noted that Newby, who was an associate justice at the time, participated in two rulings involving a program that paid tobacco farmers to transition to other crops. Newby, himself a part-time farmer in Wake County, had received payments from the program.

A utility, an environmental disaster and a justice

Newby was first elected to the state Supreme Court in 2004. He secured the chief justice’s seat in a 2020 election decided by just 401 votes.

He grew up as the son of a schoolteacher and Linotype operator in Jamestown, North Carolina.

Newby’s most recent Statement of Economic Interest, a public document North Carolina elected officials are required to file each year, shows that he has attained substantial personal wealth. The document details at least $460,000 in stock Newby and his wife own, in addition to stakes in 19 other companies. Property records indicate they own real estate with an assessed value of over $1.4 million.

Newby also reported in his 2023 filing that he and his wife each owned greater than $10,000 in stock in Duke Energy. He did not respond to a question about the size of his family’s holdings, but the couple’s stake was $20,000 at a minimum and potentially much higher.

Paul Newby reported owning $10,000 or more in Duke Energy stock for the first time on the 2021 form (North Carolina does not require officials to report amounts less than $10,000). He has reported that his wife, Macon Newby, has owned $10,000 or more in company stock since the 2015 filing, which captures their financial picture as of Dec. 31, 2014.

Newby has heard the six cases involving Duke Energy and its subsidiaries since then. The cases have concerned legal matters ranging from property easements to issues with a direct impact on the company’s bottom line, including the utility rates it charges customers and the company’s state-sanctioned monopoly. Duke Energy declined to comment for this story.

In one case, decided in December 2020, Newby sided with a state commission that permitted Duke to raise electricity rates. The complex case involved the utility’s request to pass on certain costs to consumers stemming from a disastrous spill of coal ash into the Dan River in 2014.

That year, roughly 39,000 tons of ash and 27 million gallons of ash pond water gushed into the river from Duke’s facility. Coal ash is produced when generating electricity, and it contains harmful metals, including mercury, arsenic and lead.

“Their practice was to store this ash in the most dangerous, the most polluting and the least responsible ways,” said Frank Holleman of the Southern Environmental Law Center, which represented parties opposing Duke Energy in the state case.

After the spill, three subsidiaries of Duke Energy pleaded guilty to nine federal criminal violations of the Clean Water Act in 2015. The company also agreed to pay a $68 million criminal fine.

Newby mostly concurred with the majority in the North Carolina case on Dec. 11, 2020, which allowed the rate hike but left another question to the state’s utility commission. But Newby went further than the majority, writing that the commission was correct to not assess further penalties on the company.

Newby reported owning Duke Energy stock as of Dec. 31, 2020. It is unclear if he acquired stock while the case was before the court, did so shortly after the ruling, or had holdings that appreciated in value above $10,000. Macon Newby separately owned greater than $10,000 in Duke stock during the case.

“That kind of personal investment, that’s the purest form of a conflict of interest that you can have,” said Corriher of the People’s Policy Project. “When you personally could stand to gain from the outcome of the case.”

Duke Energy and North Carolina’s attorney general announced a settlement the month after the Supreme Court’s ruling, passing some of the billions in cleanup costs on to Duke customers.

In a different case, decided in 2015, the court sided with Duke Energy over a legal question regarding coal ash lagoon permits. Then-justice Robert Edmunds did not participate in the consideration or decision of the case.

“I don’t have any recollection of the case but expect that I recused because I owned Duke stock,” he told Public Integrity.

Paul Newby, whose wife owned Duke Energy stock during the case, did not recuse himself, and joined the majority in the ruling.

Duke Energy and Newby had been linked before he ever reported owning stock in the company. A 2014 report detailed the company’s donation of over $175,000 to the Republican State Leadership Committee, a super PAC that funneled $1.1 million toward Newby’s election. The report noted there was no evidence the donation was earmarked specifically for Newby’s race.

“Duke Energy is one of the most powerful institutions in the Carolinas,” said the Southern Environmental Law Center’s Holleman. He pointed to its “tremendous influence” in campaigns, the courts and state legislatures.

The cases Newby has heard involving the company add to the list of legal matters where recusal has come under the microscope in North Carolina, all in an intensely polarized environment where control of the court recently flipped to a 5-2 Republican majority.

Groups challenging political maps asked that Newby recuse himself in 2013, since the Republican State Leadership Committee had also drafted political maps in addition to spending to boost Newby’s campaign. In 2023, plaintiffs filed two motions for Justices Phil Berger Jr., the son of the Republican state Senate president pro tem, and Tamara Barringer, a former Republican state legislator, to be disqualified from a voter ID case. And Democratic Justice Anita Earls was asked to recuse in a school funding case in 2022 due to her work with parties involved in the cases before her election to the Supreme Court.

In each instance, the justices ultimately ruled in the case.

In late August, Earls filed a federal lawsuit claiming that the Judicial Standards Commission, which reviews ethical complaints against North Carolina judges, is investigating remarks she made about the lack of diversity in the state’s court system. Newby is responsible for selecting the commission’s chair and vice chair, and has a long history of disagreements with Earls.

The investigation could lead to a range of potential punishments for Earls, a Black woman and a Democrat, including removal from the bench. There is no indication of any investigation into Newby, or any other justice, for ruling on cases in which they had a financial interest — though the Judicial Standards Commission does not make public the judges it is investigating.

Data from the commission shows it received just four complaints about Supreme Court justices in 2022, the specifics of which are unclear. The commission received dozens of complaints about alleged conflicts of interest and abuse of power from state judges at all levels last year.

The North Carolina Supreme Court briefly adopted a system in 2019 and 2020 in which the entire bench ruled on recusal cases. But when the then-Democratic majority was considering disqualifying Berger from hearing cases involving his father, and as Republicans in the state began talking about impeaching justices who supported the move, the court backed off and allowed Berger to make his own decision.

After Newby became chief justice, the court issued an order allowing justices to rule on recusal or disqualification motions directed at them. That’s precisely the system nonpartisan groups such as the National Center on State Courts, the Brennan Center and the Institute for the Advancement of the American Legal System have raised concerns about.

Still, such policies are common at state high courts in the United States.

“The public is going to be more skeptical when a judge fails to recuse herself, particularly when you have a court that is divided,” Wake Forest’s Murphy said.

Aaron Mendelson is a reporter with theCenter for Public Integrity, a nonprofit newsroom that investigates systems and circumstances that contribute to inequality in the United States.

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.