'It left us': After historic Methodist rift, feelings of betrayal and hope for future

For many, the schism that has wracked the United Methodist Church seemed inevitable, though it was an outcome few wanted.

The departure of a quarter of the church’s approximately 30,000 congregations illustrates the fallout of a prolonged and messy divorce, sparked by disagreements over issues of sexuality and gender identity.

More than 7,600 congregations signaled their intent to disaffiliate from the UMC as of Dec. 31, with many choosing to join the newly formed Global Methodist Church. The rift marks the largest denominational schism in U.S. history.

“It’s a divorce, and a messy one,” said Tracey Karcher, a former Methodist pastor who runs a general store in rural Sand Springs, Montana. “That’s all it is, if you break it down. Who gets to keep what, who gets to live with who. But both sides will move forward.”

Methodist pastors and members expressed a mix of relief, sadness and hope for the future as the two sides go their separate ways.

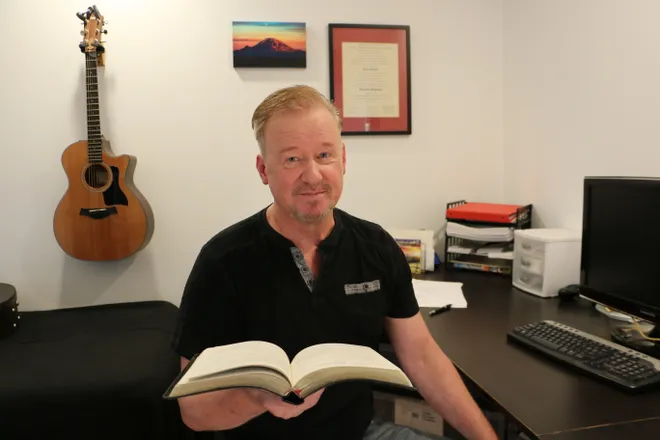

“The majority of delegates representing U.S. churches are very strong about being welcoming and affirming denominations,” said Joel Bullock, senior pastor at St. Matthew UMC in Mesa, Arizona. “I can’t speak on behalf of traditionalists, but I think they saw the writing on the wall and decided it would be in the best interests to start something new.”

Others, like Joyce Miller, a member of Christ Venice Church in Venice, Florida, saw it differently.

“As a member of a Global Methodist congregation, I can assure you that those that have chosen to follow the Biblical tradition of Methodism did not leave the UM,” Miller wrote in an email. “It left us.”

LGBT participation a divisive issue

The United Methodist Church has been one of America’s largest Protestant denominations, second in size only to Southern Baptists. While a 2015 Pew Research Center study estimated about 9 million Methodists nationwide, the church’s more recent online directory cited about 5.7 million professing members.

Over the past decade, progressive factions within the church have grown more vocal about overhauling church discipline to welcome LGBT participation, including same-sex marriage and ordination of gay clergy.

In 2016, a number of Methodist clergy came out as gay, fueling debate over the issue. But several years later at the UMC’s general conference, church leadership voted to affirm traditional policies, prompting additional blowback.

The ongoing stalemate prompted Church leaders to bring in mediator Kenneth Feinberg to help broker a resolution that ultimately included creation of a new denomination, the Global Methodist Church, as well as an exit plan allowing churches to disaffiliate “for reasons of conscience” regarding sexuality issues.

Bullock, who joined St. Matthew last summer, said no disaffiliation vote was necessary among his congregation given that leaders of the regional group to which it belongs – the UMC’s Desert Southwest Conference – had already voted to support full LGBT participation despite objections among some members.

The issue, he said, was divisive in his congregation. Bullock, who is gay, read emails and letters written by former congregation members passionately opposed to the church’s open views on sexuality.

Some, he said, left the church before he arrived in July and he can’t help but wonder whether he was the impetus.

“Some of those folks still have ties to the church,” he said. “I’ve met them personally, and they’re lovely, wonderful people – but this was something they could not participate in.”

'Is that what we've been fighting for?'

While many saw the split as inevitable, some expressed frustration with how it unfolded.

The number of “reconciling” congregations – those voting to accept full participation of LGBTQ people in church life and community – has been growing in the U.S., fueling hopes among many that the UMC as a whole might adopt similar policies and eliminate anti-LGBT language from its laws. Instead, there has been a push toward creation of global regions that could decide matters for themselves.

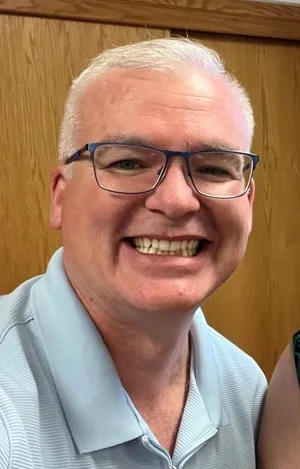

“The way it’s playing out now is very frustrating for us,” said Frank Schaefer, pastor of University UMC in Isla Vista, California. “We have lost thousands of churches. That’s a big price to pay for our denomination, and for what?”

For Schaefer, the matter is personal: A decade ago, as a pastor in Pennsylvania, he was defrocked after performing a same-sex wedding and refusing to pledge not to do so again. Schaefer was ultimately reinstated by the UMC’s judicial council, but left Pennsylvania to become chaplain and pastor at the California church near the University of California, Santa Barbara.

He’s bothered by the idea that the UMC likely won’t officially welcome LGBTQ participation as a whole.

“If we leave things just as they are, there would be congregations that could continue on a path of discrimination,” he said. “Is that what we’ve been fighting for all these years?”

Karcher, a former Methodist pastor in North Carolina, said she’ll take a backseat “until things get sorted out.”

Her issue is not with more progressive views, she said. Rather, it stems from frustration with the UMC’s inflated bureaucracy, an increase in harmful rhetoric on both sides and deteriorating respect for church discipline among regional leaders who’ve approved ordination of openly gay clergy, despite regulations declaring otherwise.

“General assemblies need to approve a change in discipline before you can start changing patterns of behavior,” she said, noting church doctrine prohibits ordination of gay clergy.

Such infighting has been ongoing for years, she said, but the harmful rhetoric being flung back and forth has gotten worse.

“That’s when I had to step back and say, I’m not going to be part of it,” she said.

Some traditionalists felt driven away

In Florida, Miller’s congregation overwhelmingly voted to disaffiliate from the denomination, she said, despite the strong emotional attachment felt among those who’d grown up in the UMC.

She said those pursuing a more progressive theology could have launched their own denomination “but decided to hijack the church instead,” laying claim to the funds and infrastructure “built by the faithful over hundreds of years.”

Schaefer, on the other hand, feels the opposite happened. Before 1972, he said, when the United Methodist Church deemed homosexuality as inconsistent with Christian doctrine, the denomination had no language prohibiting LGBT participation.

“I feel like the Church got hijacked by political conservatives,” he said. “That’s what initiated this whole fight.”

Karcher said she can understand how traditionalists might feel pushed out.

“It became a political issue, and politics have no place in the church,” she said. “When people start putting their agendas in front of serving our Lord, that’s just wrong.”

At the same time, she recognizes the impatience amo–ng progressives in the church who have spent decades fighting for change.

The issue was set to be reevaluated at the UMC’s 2020 general conference in Minneapolis but was sidelined by the pandemic, where it has remained ever since. With the split complete, Karcher hopes some sort of resolution can be reached at the UMC’s upcoming meeting in Charlotte this spring.

“It’s time,” she said. “Let’s make a decision.”

Will the split spell new beginnings – or trouble?

While some worry about the church's future, others say the break opens the door for each side to move forward.

“This will allow the United Methodists to reorganize and cut back on a lot of red tape and get back to where we once were in serving the Lord, and the world,” Karcher said.

But while the hemorrhaging has stopped, Schaefer said the struggle for LGBT recognition remains.

“This is a huge loss for everybody,” Schaefer said. “I don’t feel any kind of relief. Those who have left have to come up with cash and start over again in some ways. There’s a lot of anxiety.”

Despite declining membership, the worldwide denomination has expanded globally – particularly in Africa, where, Karcher noted, adherents are much more conservative.

“They’re extremely conservative, but they are a huge financial base,” she said. “And if African Methodists decide they want to have their own denomination, that’s going to hurt. I can see that happening down the road.”

Bullock said his hope is not only that the UMC survives but thrives, calling on leaders to affirm LGBT participation in church law “so that people really understand – not just the people in our churches, but those who drive by them – that we are inclusive, that God’s love really is for all people.”

“This is something we say every Sunday morning in the greeting after announcements,” he continued, becoming emotional. “No matter what you believe or what doubts you have, no matter what age or color of skin or who you love, you are welcome in this space. And that is the heart, I believe, of who we are as a church. I was somebody who was not accepted at one point – and now I am, and I’m thankful to be at a church that accepts me."

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.