'No reason to be scared': Why some are turning to 'death doulas' as the end approaches

LOUISVILLE, Ky. — The mid-August sun was shining, the birds were chirping, and Erin Morris was ready to discuss her impending death.

“I feel really good thinking about it,” she said. “That sounds a little odd.”

Doctors diagnosed the 36-year-old mother of two with Stage 3 breast cancer in 2018. She had a metastatic recurrence in 2020.

Over the past five years, she’s been in and out of the hospital for radiation, chemotherapy, surgeries and hormone therapy, as the cancer spread to her liver, lymph nodes, spine and bones.

She came home from her most recent hospital stay in a wheelchair and entered hospice care shortly afterward.

“But I’m the kind of person who would be more scared if I hadn’t thought about it or prepared for it or knew what was going to happen,” Morris continued, sitting propped up in her bed at her home in Louisville's East End.

The life expectancy her doctors gave her had come and gone — “two or three years ago, they said two or three years” — and her death planning was well underway.

In fact, she’d enlisted professional help.

After receiving her Stage 4 diagnosis, Morris hired a “death doula,” an end-of-life coach and advocate for her, her husband, Paul, and their children, ages 6 and 8.

With her doula’s guidance, Morris was planning her own funeral, exploring more eco-friendly alternatives to conventional burial methods and learning what she could expect to feel during the dying process.

“It brings a lot of dignity to your death,” she said. “I’ve been sick for years, and I haven’t gotten to decide when I have to switch treatments, what I have to go through, when I have to take a break, when I have to quit work. I didn’t get to control any of that.

"This is one little thing that you can control."

Like an event planner, but in a 'really bizarre way'

Morris’ death doula, Lauren Hunter-Smith, hardly resembles a Grim Reaper figure. The Lexington native wears brightly patterned dresses, has a laid-back demeanor and is quick to laugh.

Yet her interest in death began at a young age, she said, chuckling as she recalled the miniature headstones she made for the lightning bugs she accidentally squashed as a kid.

“Death is something that I feel like, culturally, we don’t talk about a lot,” she said. “It’s almost taboo to do it. And anytime anything’s taboo, I’m always slightly more interested.”

By attending various funerals throughout her life, Hunter-Smith saw firsthand how people’s unwillingness to directly confront death can make the experience even more upsetting.

Climate change is un-burying graves.It's an expensive, 'traumatic,' confounding problem.

“You have a eulogy that’s not about your person at all, or it’s a quick walkthrough, and you have a viewing of this corpse that doesn’t really look like your person,” she said. “A lot of people have just had bad death experiences. And there does come a point where you’re like, ‘Why? There’s obviously ways to do it better.’”

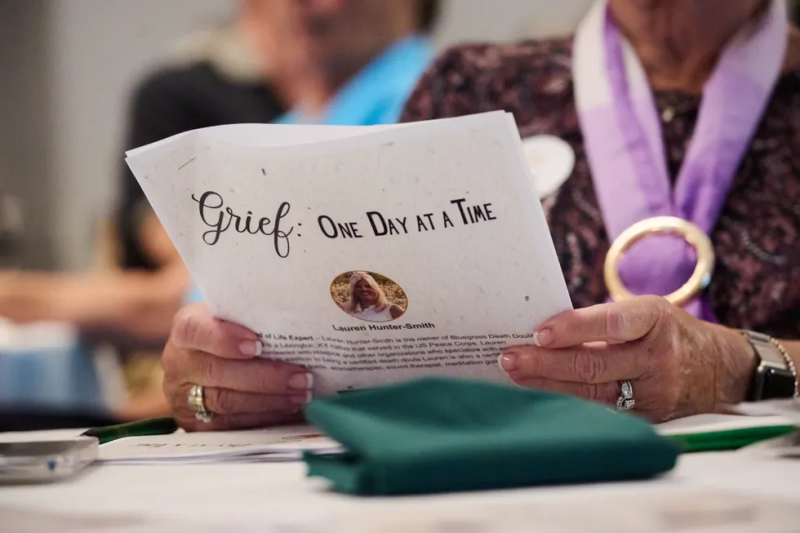

So she made it her business to do just that. In January 2022, Hunter-Smith founded Bluegrass Death Doula with the aim of guiding people through more open, informed and authentic death experiences.

In doing so, she joined a movement of death doulas that’s been rapidly gaining popularity across the United States in recent years. The COVID-19 pandemic, which brought death to the forefront of the public consciousness, seems to have been a catalyst for the profession.

Membership in the National End-Of-Life Doula Alliance more than quadrupled during the pandemic, from less than 300 people in the fall of 2019 to over 1,400 by the end of 2022. In Kentucky, there are now at least 13 death doulas, by Hunter-Smith’s count.

They go by many names — “death doula,” “departure doula,” “end-of-life doula,” “death midwife” — and they can assist with a variety of emotional and logistical needs before, during and after death, including end-of-life planning, bedside vigils, massage, meditation, aromatherapy, home funeral guidance, burial guidance, celebrant services, speaking engagements, and death education.

Unlike hospice workers, doulas don’t provide medical care, and the industry is unregulated — no official training or license is required, although many doulas, including Hunter-Smith, opt to complete an online certification program.

Hunter-Smith describes herself as akin to an event planner, “but in a really bizarre way.” She tries to tailor the dying environment to match each person’s preferences, but even those particulars aren’t as important as simply showing up as a calming, supportive presence.

“You can paint their toenails, you can read their favorite book, you can just sit with them,” she said. “Just having someone there trying to help you is a really healing thing.”

'I could focus on the beauty of it'

Across their wide range of services, many death doulas are motivated by a common cause known as “death positivity,” a movement to dismantle the taboo around death and dying in modern American culture.

Since death is inevitable, they figure we might as well talk about it — and more honest conversations, they believe, will not only help people prepare for better deaths but also to live more intentional lives.

Michelle Churchman, the owner of Shoji Bridge Departure Doula serving the Kentuckiana area, felt compelled to become a death doula after her mother died of brain cancer.

“I was a little frustrated that my mother didn’t want to talk about dying, even as it was happening,” Churchman said.

Her mother died without clarifying her wishes, making the funeral planning more difficult and disrupting Churchman’s grieving.

Lindsay Laubenstein, a death doula based in the Northern Kentucky/Cincinnati area, has hosted “death cafés” — open forums to talk about death over coffee. She emphasizes that these conversations can take place at any age, even when death seems far off in the future.

“You could be the healthiest person on the face of the planet and be like, ‘Hey, I know you do this. I want to learn more about this, so that if or when it comes to that, then I’m prepared, and I know what to look for, and I know what I want,’” Laubenstein said.

The last responder:How a pandemic upended the business of death

Indeed, Hunter-Smith said most of her clients are in their 30s and 40s, seeking assistance with completing an advance care directive. These legal documents allow an individual to choose which health care interventions they do or do not want to receive, who they want to make decisions in their stead and how they want to be treated and comforted at the end of life.

Stephanie Duckworth hired Hunter-Smith to help her complete an advance care directive at the age of 41. She said that even the process of filling out the document and asking her husband and mother-in-law to be her health care surrogates sparked thoughtful conversations and brought her closer to her family.

“It really gave me a sense of peace and wellbeing to be filling this out at a time when I’m not stressed,” she said. “I could focus on the beauty of it and making it a joyful and easy process for my friends and loved ones.”

'A party to die for'

With her glittery eyeshadow, dangly earrings, and multicolored, elementary-school-art-teacher clothes, Denise Metzger takes death positivity to the next level.

In 2005, doctors diagnosed Metzger’s oldest daughter, Jonnae, with leukemia at age 12. She “party-hopped” — the term Metzger prefers over “died” or “passed away” — three years later.

In the final days of Jonnae’s life, Metzger threw her a Hollywood red carpet-themed celebration of life at a local movie theater. Her daughter got to hear her friends and family reflect on how much she meant to them and to share her wisdom with them.

While the conventional funeral industry throws “pity parties,” Metzger said, this event was meant to be different, a reminder of the gift of life underlying the pain and grief of death.

“Jonnae, even though she was very young, did not want people to be worried or afraid or sad,” Metzger said. “She didn’t want any tears.”

From there, Metzger got the idea to start a business called Surprise Invite to help people plan “celebration of life” events that are elaborate, personalized and fun. Her taglines are “you’re invited to a party to die for” and “you can be the life of the party, even when you’re dead.”

“What happens after the last breath?” she asked. “I suggest it’s a surprise. None of us really know. And you can surrender to the not-knowing and just play with it.”

Metzger’s own funeral is, of course, already planned out. There will be stilt walkers, aerial ribbon dancers and a tribal drum ceremony. Her guests will watch a commemorative documentary video she created of her family, friends and coworkers talking about the fond memories they shared.

“My boys will roll their eyes and be like, ‘Jesus, she’s still here,’” she chuckled. “They’ll know who I was, they’ll know that I lived a full life, they’ll be inspired by the life that I lived, and they’ll know that I was OK with it when the time came.”

What is a 'green burial'?

In addition to alternative funeral options, many death positivity advocates are also proponents of alternative burials. Traditional embalming, cremation and burials have a large environmental footprint — the carbon dioxide emitted from one cremation is equivalent to a nearly 500-mile car ride.

Hunter-Smith is an adviser to Windy Knoll Memorial Sanctuary in Lawrenceburg, the only green burial cemetery in Kentucky available to the general public. Members of the Unitarian Universalist Church of Lexington founded the cemetery in 2022, and it conducted its first burial in July.

The cemetery buries people in wicker caskets or cloth shrouds, so their bodies can decompose much more quickly than they would in steel caskets and concrete vaults. Not only does this reduce wasteful materials with each burial, it allows the same grave site to be reused in a matter of years rather than centuries.

Brian Hall, secretary of the board of Windy Knoll, said when he learned about green burials a few years ago, it “immediately clicked.”

“The more I thought about the amount of energy that goes into cremation and how that contributes to climate change — that’s not what I want from my final act,” he said.

Other eco-friendly burial options include human composting (placing the body in a chamber with natural materials, accelerating decomposition even more), and alkaline hydrolysis (using alkaline chemicals to break down a body in a chamber of water).

For people who opt for these alternative burials, the ecological motives are often intertwined with spiritual ones — they are drawn to the idea of becoming part of the earth and something greater than themselves.

“It’s a much more gentle goodbye,” Hunter-Smith said.

Access issues for end-of-life care

The ability to hire a death doula, and to arrange for a “good death” more broadly, are privileges which many people lack.

Around a third of Americans age 65 or older are economically insecure, according to the National Council on Aging.

A spot at Windy Knoll costs $3,000, several times more than a conventional cremation, and death doula services are not covered by insurance, including Medicare or Medicaid.

Language and education barriers, cultural differences and distrust of the health care system make advance care directives and hospice care less accessible for some.

These disparities led Churchman to begin the process of establishing a nonprofit with another death doula friend, which would allow them to provide their services free of charge.

“We don’t want to ever have to turn someone away who wants our help,” Churchman said.

Hunter-Smith is also in the early stages of establishing her own death care nonprofit. She plans to offer free advanced care directives, then expand to create home funeral leagues — groups of volunteers who could assist with home funerals for individuals who don’t have a support network.

Her ultimate dream is to create a cooperative cemetery for green burials, where people could work at others’ burials to earn their own spot in the future. She envisions holding picnics, weddings and miniature golf on the grounds.

“I want people to feel comfortable relating to death in a different way there,” she said.

Carrying out her plans

Time seemed to pass more slowly for Morris as summer passed its halfway point, but she'd been trying to keep busy.

She embroidered the flying balloon house from “Up.” She joined a book club, and she liked reading novels involving “dramatic crime stuff” and murders.

She was crafting things to leave behind to her loved ones: a pillow for her daughter, thumbprint stones for her friends, a Spotify playlist for her funeral. She spoke of looking forward to finally leaving the house the next day, to watch her daughter perform on the keyboard at her very first concert.

And yet ...

“Nobody can say they don’t feel scared at all,” she said, brushing away a tear. "But, no, I don’t feel very scared. No reason to be scared. Everyone you know has done it or will do it in the future."

Morris died exactly one week later, on the morning of Aug. 18.

“It really did kind of knock the air out of me,” Hunter-Smith said. She described the strange mix of emotions she felt in the following days — she was devastated for Morris’ husband and young children, yet proud to see them carrying out her plans with confidence.

Morris was Hunter-Smith’s first client to opt for human composting. Her family conducted a home funeral, then sent her body to a facility in Seattle, where it was reduced into usable soil over the course of several weeks. Part of the soil went into a park, and the rest will be sent back to her family.

At that point, she was also Hunter-Smith’s fourth client to pass away within 10 days. That night, Hunter-Smith set up an altar for all of them in her home, putting out water, coffee, salt, sugar and flowers alongside their pictures.

“I know how my services end, of course, but it’s still sad,” she said. “That’s just part of it.”

More from Boyd's Station:Written out of existence? Native Americans in Kentucky push for recognition of culture

This article is part of a collaboration between The Courier Journal and Boyd's Station, a Kentucky non-profit that provides emerging artists and student journalists a rural place to hone their craft. Sophia Liang received the 2023 Mary Withers Rural Writing Fellowship grant at Boyd's Station.

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.