‘Murder in progress': Police tried to spare attacker’s life as they saved woman from assault

COHASSET, Mass. (AP) — Detective Lt. Gregory Lennon glimpsed at the modest duplex from his patrol car while waiting for backup that was seconds behind. This was a wellbeing check, among the most common calls in this quiet seaside town near Boston, but Lennon knew better than to go in alone.

Everything seemed quiet when Lennon stepped out of the cruiser and into the winter darkness to greet two arriving officers. The downstairs shades were up, lights on.

It was two days after Christmas 2018, and Lennon was supposed to be home with his family. When an officer called in sick, Lennon agreed to cover a night shift. After more than two decades in law enforcement, he knew staffing shortages come with the job.

It had been a slow night. Now a concerned mother wanted police to check on her 25-year-old son, who she said suffered from mental health challenges.

She was away and a neighbor called her to say he heard loud crashing noises coming from the house. Her son was not answering his phone.

The officers knocked on the front door but no one answered, so they found an unlocked sliding-glass door, and eased it open.

“Cohasset police,” the officers said. “Erich, are you home?”

They were calling out for Erich Stelzer, a 6-foot, 6-inch bodybuilder who liked to post workout videos online.

That’s when Lennon heard the cry for help that changed his life.

“He’s killing me,” a woman screamed. “Help me, he’s killing me!”

The officers dashed to an upstairs bedroom. The door was locked. Lennon kicked it in.

The walls looked like they had been painted with blood. Stelzer was on the floor, soaked in red and holding a woman in a headlock with a piece of broken glass to her throat. Both were naked. Her body was so battered Lennon wondered if she was still alive.

She was, but barely. In that moment, 24-year-old Maegan Ball figured she was seconds from death. She’d met Stelzer on a dating app. Now he was convinced that Ball was the devil, and that she had killed his mother and sister. It was her turn to die.

Stelzer had beaten her face until bones shattered, tried to drive a wooden stake into her stomach, stabbed her with a knife and shards of glass, and gouged her eye.

“A murder in progress,” Lennon thought.

“You’re very quickly contemplating whether you’re going to have to use deadly force,” he recalled.

Ball was willing herself to stay conscious. Suddenly, she heard a voice: “Crawl to me.”

Somehow, she still doesn’t know how, Ball slipped away from Stelzer. She couldn’t see through the blood in her eyes, but she followed the voices.

Keep crawling, Lennon pleaded. He kept his pistol sights on Stelzer, who was growling and screaming, “I am God.” The other two officers holstered their guns and drew their Tasers.

As Stelzer moved toward the officers, one fired his Taser, and its darts lodged in the man’s skin. The second officer also fired his Taser. They shocked Stelzer multiple times as he thrashed on the floor, dislodging the darts. During his autopsy, a piece of Taser wire was still clenched in his fist.

Finally, Lennon saw an opportunity to handcuff Stelzer with his hands in front. It wasn’t ideal, but would have to do. Soon, Stelzer was barely breathing. The officers and medics labored to revive him. They couldn’t.

Stelzer is one of more than 1,000 people who died over a decade after police used common use-of-force tactics that, unlike guns, are meant to stop people without killing them, according to an investigation led by The Associated Press. In some cases, police used overwhelming force even though someone posed little threat. In others, like with Stelzer, officers faced extreme violence and still tried to keep everyone alive.

The officers weren’t the only ones who had tried to save Stelzer. His family had, too.

Stelzer had been abusing steroids, marijuana, alcohol and Adderall, an amphetamine used to treat attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. He also struggled with his mental health. Just two days before he died, Stelzer experienced a crisis at a family Christmas gathering, where he ranted incoherently about good and evil, and the beheading of a French president.

His sister followed him to a gas station and summoned an ambulance. Stelzer refused treatment, and his symptoms were not severe enough to force him to get help.

The family’s last hope was an “intervention specialist” to coax him into a treatment facility in Florida. The intervention was expected a day or two after Stelzer’s fatal encounter.

He had not suggested he was planning to hurt someone else, but Stelzer’s family was concerned he would harm himself.

“We knew that he was very sick and we were very worried about the potential for something bizarre happening, which is why we were frantically trying to get him help,” his sister, Gretchen Stelzer, said. Stelzer’s family remembers him as a kind and loving child overcome by mental health challenges as an adult.

She said the officers “did what they had to do to protect themselves.”

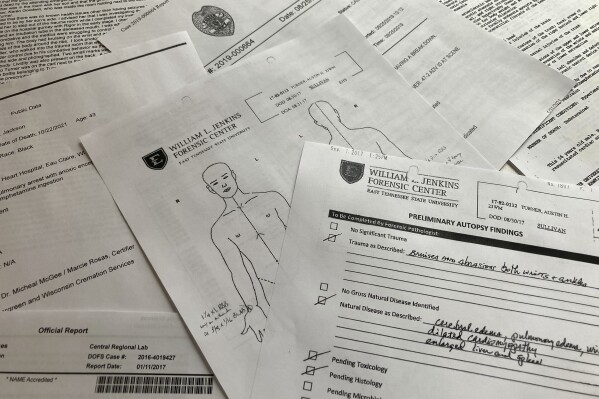

The medical examiner’s office said Stelzer died from a combination of a heart problem, the altercation, Taser shocks and amphetamine. Stimulants, particularly methamphetamine and cocaine, were the most common drugs used by the people who died in other cases analyzed by AP and its partners at the Howard Centers for Investigative Journalism.

Days after the attack, the officers paid a cathartic visit to Ball in the hospital.

“They said they just wanted to see me and make sure I was OK,” Ball recalled. She suspected it was “kind of to help them, too.”

Ball’s long recovery included reconstructive facial surgeries. She met with the officers a year later and formed a bond. Ball and her husband run Dogs of War, a business that breeds and trains canines for protection.

The officers were placed on leave, standard procedure when police are involved in deaths. The district attorney investigated and cleared the officers, saying they would have been justified in shooting Stelzer.

Lennon remains proud they did not. Still, he cannot shake the memories of that night. The mayhem lasted minutes. The memories linger.

“It’s a profound realization to contemplate having been involved in someone’s death, especially when that was not your intention,” Lennon said. “We did the best that we could do.”

___

Editor’s note: The information in this story is based on a 157-page report from the district attorney’s office and interviews with Lennon, Ball, Cohasset Police Chief William Quigley and Stelzer’s sister, Gretchen Stelzer.

___

Mohr reported from Jackson, Mississippi. Jennifer McDermott in Providence, Rhode Island, and Patty Nieberg in Denver contributed.

___

This story is part of an ongoing investigation led by The Associated Press in collaboration with the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism programs and FRONTLINE (PBS). The investigation includes the Lethal Restraint interactive story, database and the documentary, “Documenting Police Use Of Force,” premiering April 30 on PBS.

___

The Associated Press receives support from the Public Welfare Foundation for reporting focused on criminal justice. This story also was supported by Columbia University’s Ira A. Lipman Center for Journalism and Civil and Human Rights in conjunction with Arnold Ventures. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

___

Contact AP’s global investigative team at [email protected] or https://www.ap.org/tips/

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.