Schools are censoring websites for suicide prevention, sex ed, and even NASA

This article was copublished with The Markup, a nonprofit, investigative newsroom that challenges technology to serve the public good.

A middle school student in Missouri had trouble collecting images of people’s eyes for an art project. A high school junior couldn’t read analyses of the Greek classic “The Odyssey” for her language arts class. An eighth grader was blocked repeatedly while researching trans rights.

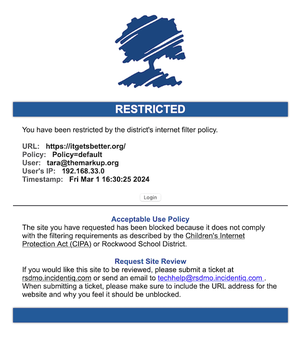

All of these students saw the same message in their web browsers as they tried to complete their work: “The site you have requested has been blocked because it does not comply with the filtering requirements as described by the Children’s Internet Protection Act (CIPA) or Rockwood School District.”

CIPA, a federal law passed in 2000, requires schools seeking subsidized internet access to keep students from seeing obscene or harmful images online — essentially porn.

School districts all over the country, like Rockwood in the western suburbs of St. Louis, go much further, limiting not only what images students can see but what words they can read. Records obtained from 16 districts in 11 different states show just how broadly schools block content, forcing students to jump through hoops to complete assignments and keeping them from resources that could support their health and safety.

Students are prevented from going to websites that web-filtering software categorizes as “education,” “news,” or “informational.” In some districts, they can’t access sex education websites, abortion information, or resources for LGBTQ+ teens—including suicide prevention.

Virtually all school districts buy web filters from companies that sort the internet into categories. Districts decide which categories to block, often making those selections without a complete understanding of the universe of websites under each label—information that the filtering companies consider proprietary. This necessarily leads to overblocking, and The Markup found that districts routinely have to create new, custom categories to allow certain websites on a case-by-case basis. Students and teachers, meanwhile, suffer the consequences of overzealous filtering.

The filters do keep students from seeing pornographic images, but far more often they keep them from playing online games, browsing social media, and using the internet for legitimate academic work. Records from the 16 districts include blocks that students wouldn’t necessarily notice, representing elements of a page, like an ad or an image, rather than the entire site, but they reveal that districts’ filters collectively logged over 1.9 billion blocks in just a month.

“We’re basically trapped in this bubble, and they’re deciding what we can and can’t see,” said 18-year-old Ali Siddiqui, a senior at a San Francisco Bay Area high school.

The blocks raise questions about whether schools’ online censorship runs afoul of constitutional law and federal guidance.

Catherine Ross, professor emeritus of law at George Washington University and author of a book on school censorship, called the blocks “a very serious concern—particularly for those whose only access is through sites that are controlled by the school,” whether that access is limited because they can’t afford it at home or simply can’t get it.

“We’re setting up a system in which students, by the accident of geography, are getting very different kinds of education,” Ross said. “Do we really want that to be the case? Is that fair?”

Though banned books get more attention than blocked websites in schools, some groups are fighting back. Students in Texas are supporting a state law that would limit what schools can censor, and the American Library Association hosts Banned Websites Awareness Day each fall. The ACLU continues to fight the issue at the local level more than a decade after wrapping up its national “Don’t Filter Me” campaign against school web blocks of resources for the LGBTQ+ community.

Yet as the culture wars play out in U.S. schools, Brian Klosterboer, an attorney with the ACLU of Texas, said there are signs the problem is getting worse. “I’m worried there’s a lot more content filtering reemerging.”

'Human sexuality'

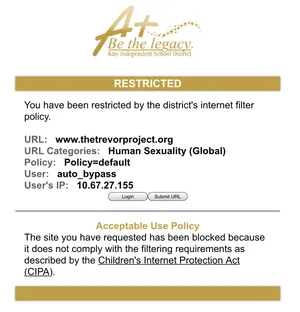

A middle school teacher in the Rockwood School District has a poster on her wall about The Trevor Project, whose site offers suicide prevention resources specifically for LGBTQ+ young people. But middle schoolers can’t access the site from their school computers.

Nor can they visit It Gets Better, a global nonprofit that aims to uplift and empower LGBTQ+ youth. They can, however, see anti-LGBTQ+ information online from fundamentalist Christian group Focus on the Family and the Alliance Defending Freedom, a legal nonprofit the Southern Poverty Law Center labeled an anti-LGBTQ+ hate group in 2016.

Bob Deneau, the school district’s chief information officer, said his department works with teachers to determine the curricular benefit of unblocking certain categories. “When we look at it, we say, ‘Is there educational purpose?’” he explained.

The policy is to block first and only unblock in the face of a compelling case.

Rockwood School District uses web filtering software called ContentKeeper, which has a “human sexuality” category that captures informational resources, support websites, and entertainment news designed for the LGBTQ+ community.

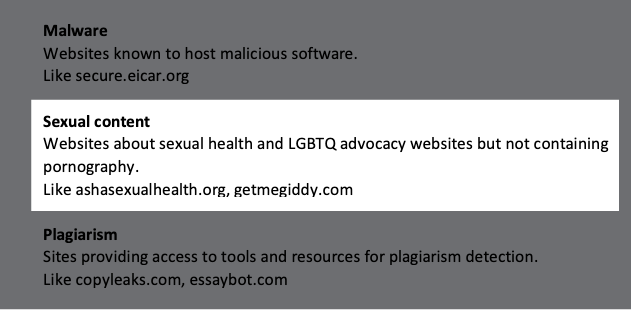

The ACLU’s “Don’t Filter Me” campaign, launched in 2011, urged filtering companies to get rid of categories like this one and the “sexual content” category a widely used rival filter called Securly has. The Securly category covers “websites about sexual health and LGBTQ+ advocacy websites,” not, as one might think, porn.

The ACLU won a lawsuit against Missouri’s Camdenton R-III School District in 2012, successfully arguing that the district’s filter amounted to viewpoint discrimination because it blocked access to supportive LGBTQ+ information while allowing access to anti-LGBTQ+ sites.

Yet complaints have continued. Cameron Samuels first encountered blocks to LGBTQ+ web pages during the 2018–19 school year while working on a class project as a ninth grader in Texas’ Katy Independent School District. Like Rockwood, Katy uses ContentKeeper to filter the web; to Samuels, the LGBTQ+ category of blocks felt like a personal attack. Not only did Samuels find that the LGBTQ+ news source The Advocate was blocked, the teen also couldn’t visit The Trevor Project.

“The district was blocking access to potentially lifesaving resources for me and my LGBT identity,” Samuels said.

The teen went on to petition Katy ISD to unblock the sites and succeeded at the high school level, but Anne Russey continues to fight for access for younger students. A mom of two elementary schoolers in the district and a professional therapist for LGBTQ+ adults, Russey has gone so far as to file a discrimination complaint with the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights.

“My biggest fear is that we lose a student as a result of this filter,” she said. The Trevor Project estimates that at least one LGBTQ+ person between the ages of 13 and 24 attempts suicide every 45 seconds.

Representatives from Impero did not return repeated calls and emails requesting comment about ContentKeeper for this story.

Securly’s vice president of marketing, Joshua Mukai, offered no comment on the idea that blocking LGBTQ+ advocacy websites through the “sexual content” category is discriminatory.

Reproductive health

Maya Perez, a senior in Fort Worth, Texas, is the president of her high school’s Feminist Club, and she and her peers create presentations to drive their discussions. But research often proves nearly impossible on her school computer. She recently Googled “abortion access Texas” and was stymied.

“Page after page was just blocked, blocked, blocked,” Perez said. “It’s challenging to find accurate information a lot of times.”

What students say:A digital book ban? High schoolers describe dangers, frustrations of censored web access

Alison Macklin spent almost 20 years as a sex educator in Colorado; at the end of her lessons, she would tell students that they could find more information and resources on plannedparenthood.org. “Kids would say, ‘No, I can’t, miss,’” because of the filters, she remembered. She now serves as the policy and advocacy director for SIECUS, a national nonprofit advocating for sex education.

Only 29 states and the District of Columbia require sex education, according to SIECUS’ legislative tracking. Missouri is not one of them. The Rockwood and Wentzville school districts in Missouri were among those The Markup found to be blocking sex education websites. The Markup also identified blocks to sex education websites, including Planned Parenthood, in Florida, Utah, Texas, and South Carolina.

In Manatee County, Florida, students aren’t the only ones who can’t access these sites — district records show teachers are blocked from sex education websites too.

The breadth of the internet

Rockwood School District sophomore Brooke O’Dell most frequently runs into blocked websites when doing homework. Sometimes she can’t access PDFs she wants to read. Her workaround is to pull out her phone, find the webpage using her own cellular data, navigate to the file she wants, email it to herself, and then go back to her school-issued Chromebook to open it. When it’s website text she’s interested in, O’Dell uses the Google Drive app on her phone to copy-and-paste text into a Google Doc that she can later access from her Chromebook. She recently had to do this while working on a literary criticism project about the book “Jane Eyre.”

Recounting her frustration, O’Dell bristled at the need for any web filter at all.

“While you’re in school, they are in charge of you,” she said, “but that doesn’t mean they need to control everything you’re doing.”

In Forsyth County Schools in Georgia, which blocks a relatively narrow set of categories, records obtained by The Markup reveal a spate of blocked YouTube videos: several about Picasso as well as history videos, a physics lesson, videos of zoo animals, and children’s songs about the seasons and days of the week.

Mike Evans, the district’s chief technology and information officer, said the district tries to apply filters fairly. “We’ll always have different families on one side or another,” Evans said. “Some would rather have things more restricted if they don’t agree with any LGBTQ-type material or video that might be available, but we try to stay away from that type of (filtering) altogether.”

Among the 16 districts that released records about their blocked websites, 13 shared the categories tied to the blocks. Games and social media were the most frequently blocked categories, along with ads, entertainment, audio and video content, and search engines.

Sites labeled “porn” or “nudity” didn’t crack the top 10 categories blocked in any district. Only in Palm Beach County, Florida, and Seattle were they even in the top 20.

In Manatee County, Florida, students in the schools can’t access the local public library catalog; most social media platforms; or sites with audio and video content including Fox Nation, Spotify, and SoundCloud.

The Manatee County district’s chief technology officer, Scott Hansen, described a filtering policy that errs on the side of blocking. If a category isn’t seen as having an explicit educational purpose, it is blocked.

Hansen said he gets few requests from teachers to unblock websites.

But interviews with students and teachers around the country indicate many have simply resigned themselves to being kept from much of the internet. The overarching rationale for the filters — keeping students safe — seems unimpeachable, so few people try to fight them. And schools have the right to limit what they make available online. CIPA lets the FCC refuse internet subsidies to school districts that don’t filter out porn, but the law doesn’t identify any consequence for excessive filtering, giving districts wide latitude.

In a survey by the Center for Democracy and Technology, nearly three-quarters of students said web filters make it hard to complete assignments. Kristin Woelfel, a policy counsel at CDT, said she and her colleagues started to think of the web filters as a “digital book ban,” an act of censorship that’s as troubling as a physical book ban but far less visible. “You can see whether a book is on a shelf,” she said. By contrast, decisions about which websites or categories to block happen under the radar.

In the Rockwood School District, O’Dell recognizes that web filters prevent students from playing games on their computers, but she doesn’t believe technology should play that role.

“It’s not really teaching kids the responsibility of when to pay attention in class,” she said. “It kind of just takes that entire part of learning completely away.”

A stubborn status quo

The American Library Association has been calling for a more nuanced approach to filtering the internet in schools and libraries since 2003, when it failed to convince the Supreme Court that CIPA is unconstitutional.

In 2011 the FCC emphasized that blanket blocks of social media platforms are not consistent with CIPA, and the original law only says districts are required to block obscene or harmful images.

Deborah Caldwell-Stone, director of the ALA’s Office for Intellectual Freedom, called CIPA “a handy crutch” for censorship that is not justified by the law. “The FCC makes it clear that it’s not (justified), but there’s no remedy for the kind of activity other than going to court,” she said, which is too expensive and time-consuming for many families.

Lawsuits also have limited reach, often changing behavior in only one small part of the country. Rockwood School District has a filter doing what the ACLU sued Camdenton for over a decade ago and the two districts are in the same state, just 150 miles apart. Battling discrimination carried out via web filters is like a game of whack-a-mole in a nation where much of the decision-making is left to more than 13,000 individual school districts.

And the question of what students have a right to see is only getting murkier. In 2023 alone, the American Library Association tracked challenges to more than 9,000 books in school libraries nationwide.

But it doesn’t have to be that way. Schools could use the wide latitude the FCC leaves them to take a more hands-off approach to web filtering.

In Texas, Samuels, the Katy ISD grad who encountered blocks to LGBTQ+ web pages, co-founded Students Engaged in Advancing Texas to fight for open access to information statewide. The group supported legislation introduced in the state legislature last year that would have prohibited schools from blocking websites with resources about human trafficking, interpersonal or domestic violence, sexual assault, or mental health and suicide prevention for LGBTQ+ individuals. It didn’t go anywhere, but Samuels hopes it will in the future.

Unfortunately, Samuels said, “Censorship is a winning issue right now.”

This article was copublished with The Markup, a nonprofit, investigative newsroom that challenges technology to serve the public good. Sign up for its newsletters here.

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.