Quality early education can be expensive or hard to find. Home visits bring it to more families

PUEBLO, Colo. (AP) — Standing in her living room, Isabel Valencia sets up her makeshift tennis serve with the materials on hand: a green balloon for a ball and a ruler affixed to a paper plate for a racket.

She bats the balloon to her home visitor, Mayra Ocampo, and they pass it back and forth, counting each return, offering encouragement and laughing at their mistakes.

The moment is light and playful, as it likely will be later in the week, when Valencia tries the same activity with her 4-year-old daughter Celeste. But Ocampo takes care to explain what’s happening beneath the surface: They’re not just playing tennis. They’re building social skills. They’re working on hand-eye coordination. And they’re practicing numeracy.

Instructor Mayra Ocampo, left, prepares materials before starting home visit instruction for Isabel Valencia in her living room in Pueblo, Colo., Wednesday, Feb. 28, 2024. (AP Photo/Eric Lars Bakke)

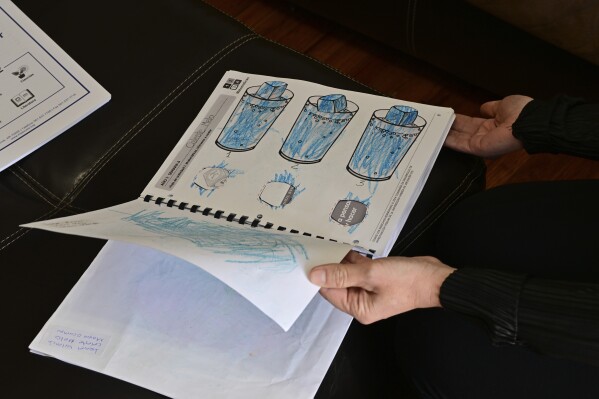

Parent Isabel Valencia holds the first-year program portfolio of her daughter, Celeste, in her living room in Pueblo, Colo., on Wednesday, Feb. 28, 2024. (AP Photo/Eric Lars Bakke)

Valencia, who came to the U.S. from Colombia a few years ago, found Ocampo through a free program that supports families with their children’s early learning and development.

Home visiting programs have provided a lifeline for families, especially those for whom access to quality early education is scarce or out of reach financially. The programs, which are set to expand with new federal support, are proven to help prepare children for school but have reached relatively few families.

It was during a trip to the grocery store in 2022 with her two young kids that somebody told Valencia about the home visiting program. She had moved to Pueblo, Colorado, only a few months earlier and was feeling isolated. She hadn’t met anyone else who spoke Spanish.

“I didn’t leave my house,” she says through an interpreter, “so I thought I was the only one.”

The Home Instruction for Parents of Preschool Youngsters program, known as HIPPY, provides families with a trained support person — in Valencia’s case, Ocampo — who visits their home every week, showing them how to engage their children with fun, developmentally appropriate activities.

The HIPPY program is unique for its two-generation approach. Through regular home visits and monthly group meetings, parents learn how to promote early literacy and social-emotional skills from staff who went through the program themselves and often share the same language and background as the families they serve.

Home visitor Amanda Pedlar and parent Bridget Collins check their smiles in a mirror, illustrating what someone might look like when they are happy, during a role-playing activity on March 4, 2024, in San Antonio, Texas. (Emily Tate Sullivan/EdSurge via AP)

The program is primarily implemented in low-income neighborhoods, as well as through school districts and organizations reaching immigrant and refugee families, says Miriam Westheimer, chief program officer for HIPPY International, which operates in 15 countries and 20 U.S. states.

In the U.S., two dozen home visiting models have received a stamp of approval — and with it, access to funding — from the federal government’s Maternal, Infant and Early Childhood Home Visiting program. While some emphasize preparing toddlers for school, others send social workers or registered nurses who focus on maternal and child health.

An estimated 17 million families nationwide stand to benefit from the type of voluntary, evidence-based home visiting services that Valencia receives. Yet in 2022, only about 270,000 did.

“That is purely because of resources,” said Dr. Michael Warren, of the Maternal and Child Health Bureau, which oversees the MIECHV program. “If more resources exist, more families can be served.”

Fortunately, he says, reinforcements are on the way.

The federal investment in the MIECHV program is set to double from $400 million to $800 million annually, by 2027. Beginning this year, the federal government will match $3 for every $1 in non-federal money spent on home visiting programs, up to a certain amount.

Now in her second year of the HIPPY program, Valencia is a more confident parent. She says the structured curriculum she follows, paired with Ocampo’s support, have helped her prepare her daughter to thrive in preschool.

“As parents, it’s hard to balance everything — work, kids, house,” says Ocampo, noting that many families in her caseload face language barriers and economic challenges such as food insecurity. “But you want to give the best to (your kids).”

Home visiting gives parents the tools to do it, she says.

Visitors supply books and materials for parents to carry out activities, as well as diapers and wipes and referrals to food pantries, public assistance programs, early intervention services and mental health professionals. They also explain the developmental importance of talking, reading and singing with young children, asking them questions, and praising them.

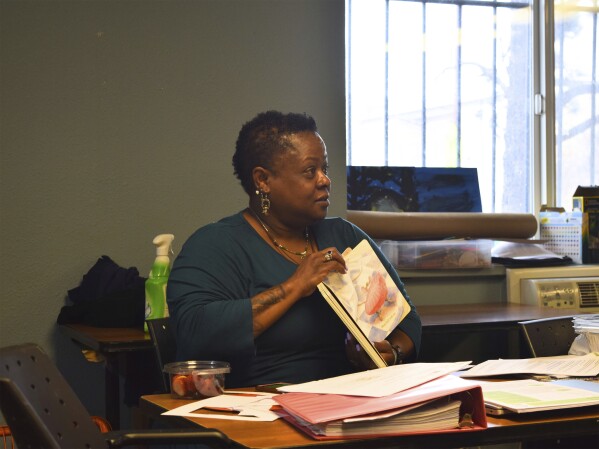

Melanie Collier, HIPPY coordinator for Spring Institute, a nonprofit organization in Denver, Colo.,, talks to home visitors about a book they will soon be introducing to families in their case load, on March 12, 2024. (Emily Tate Sullivan/EdSurge via AP)

They communicate a simple but potent message to parents: Everything they need to help their children flourish is probably already at home.

A math lesson can be found among a bag of beans or a pocketful of loose change. Kids can practice literacy skills by searching for items around the house that start with a particular letter.

“Not only does it help the child, it helps the parents,” says Avis Stallworth-Ellis, the HIPPY coordinator for Montgomery Public Schools in Alabama, which uses federal money to offer home visiting programs. “It gives them a different way to think.”

The most valuable outcome, families and home visitors say, is the bond forged between parent and child.

“It’s good for them and good for you,” says Ocampo. “They’re thinking you are playing, but they’re really learning.”

Parents also become better advocates for themselves and their children, and research has shown that kids are better prepared for school.

Instructor Mayra Ocampo, prepares materials for a science lesson to demonstrate to Isabel Valencia in Valencia’s home in Pueblo, Colo., Wednesday, Feb. 28, 2024. (AP Photo/Eric Lars Bakke)

Last fall, when Valencia’s daughter started preschool, the teacher told her that Celeste was more advanced than many of her classmates — evidence, Valencia says, of the cognitive and social-emotional skills they’ve worked on during daily activities.

Although Celeste is now enrolled in an early education program, Valencia has continued with the home visiting. “It’s a complement” to preschool, says Valencia, who recently became a HIPPY home visitor herself.

While home visiting is not intended to be a replacement for other early learning experiences, it can help to establish a strong foundation, especially for the many families who find early education programs inaccessible or unaffordable.

Throughout Pueblo, a city of 112,000, kindergarten teachers have noted students who receive home visiting services have longer attention spans, follow instructions better and have more developed motor skills, according to Maria Chavez Contreras, home visiting program manager at the community-based organization that hosts HIPPY in Pueblo.

“When they get to school, it’s nothing new for them,” says Chavez Contreras. “They’re carrying it over from home.”

Home visitor Fatema Zamani and her 4-year-old daughter Kaenat build a homemade hammock, imitating a scene from a children’s book they just read on April 3, 2024, in Denver, Colo. (Emily Tate Sullivan/EdSurge via AP)

Fatema Zamani, a Denver-based home visitor, says she hears from parents in her caseload — all recent arrivals from Afghanistan, where Zamani emigrated from in 2016 — about how impressed their children’s kindergarten teachers are.

Her own daughter, 4-year-old Kaenat, is in the HIPPY program and can recite her alphabet, count, and identify shapes and colors. “She is ready for preschool,” Zamani says.

She can tell the parents she works with are more confident, more curious — including those who started out reticent because they cannot read.

They’ve since spread the word. Zamani says she now has a long wait list.

___

This article was co-published with EdSurge. EdSurge is a nonprofit newsroom that covers education through original journalism and research. Sign up for their newsletters.

___

The Associated Press’ education coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.