Can Mississippi Advocates Use a Turtle To Fight a Huge Pearl River Engineering Project?

TYLERTOWN, Miss.—On a clear, hot summer afternoon along the Bogue Chitto creek at Walker’s Bridge Water Park in southern Mississippi, Noah Devros dives into the murky water with a flashlight and cheap plastic dive mask. He emerges holding a small turtle.

Devros is a graduate student and researcher from the University of Southern Mississippi, and he’s working to tag and inventory the Pearl River map turtle, which in July was listed as “threatened” under the Endangered Species Act. The rule effectively makes it illegal to harm the animals in any way.

Armed with these new protections, this turtle could be the catalyst for halting a huge and controversial engineering project upriver in Jackson, Mississippi, known locally as “One Lake.”

Explore the latest news about what’s at stake for the climate during this election season.

Devros weighs and tags the map turtle before placing her back into the sand.

“They’re really charismatic,” said Devros, adding that the species is important to the local ecology; they eat invasive clams and clean the water by consuming algae.

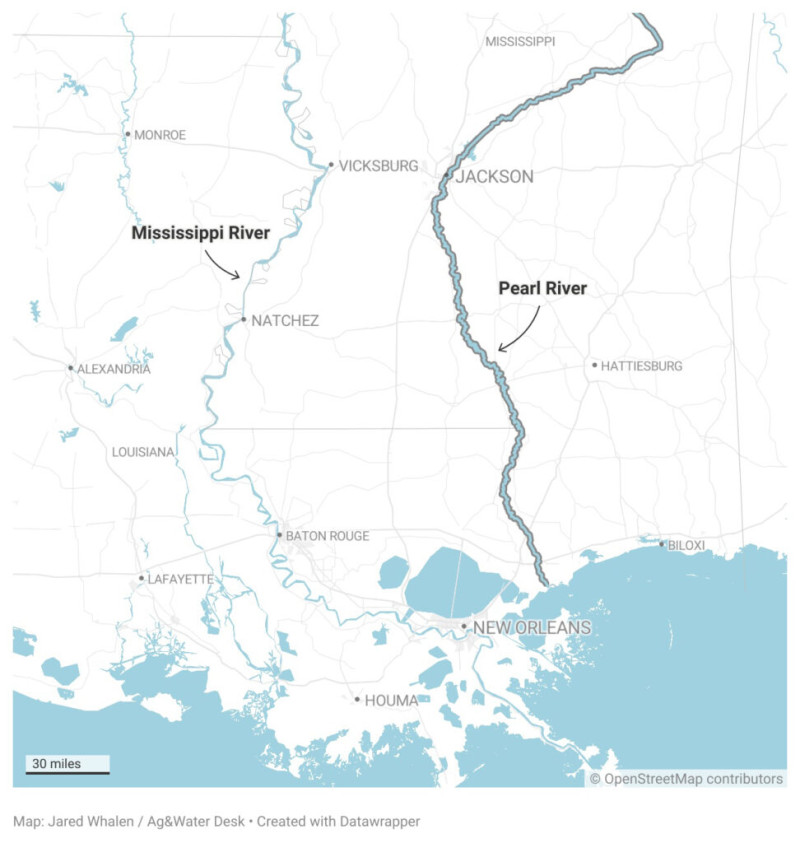

The Pearl River map turtle, named after the one place it calls home and the maplike details on its back, relies on the running waters of the Pearl River basin in Mississippi and Louisiana to eat, nest and live.

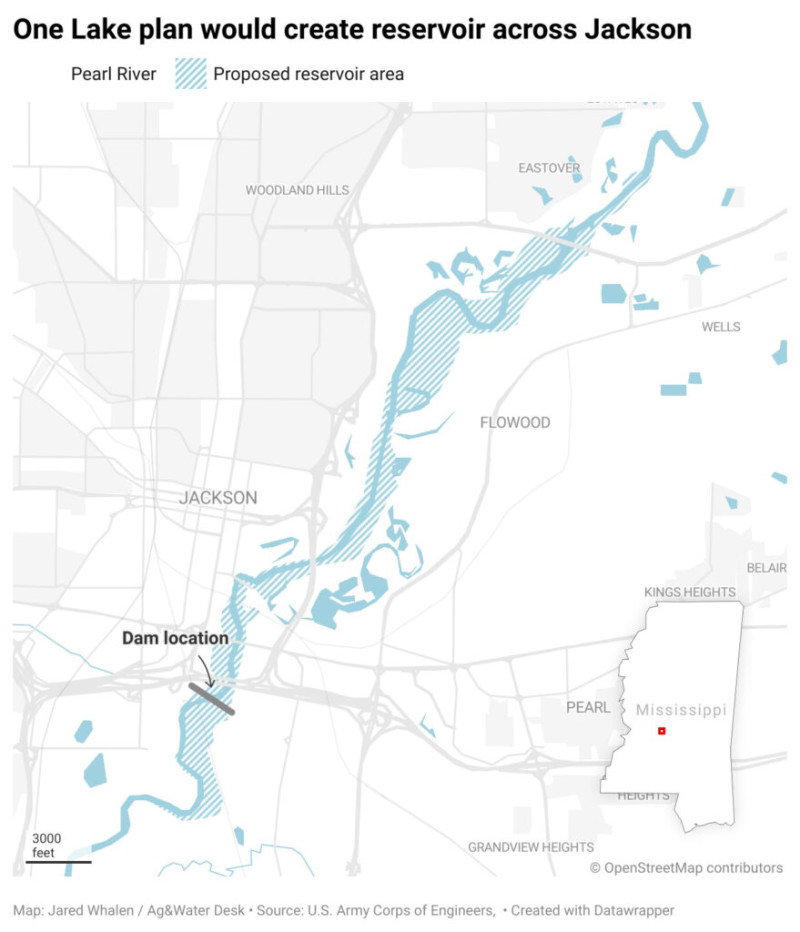

But upstream, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has put forward a plan to reduce flooding from the Pearl River in Jackson. The plan—one of four flood-control proposals being considered by the agency—would dredge and widen a section of the Pearl and build a new dam across the river, creating an artificial lake spanning roughly 1,700 acres.

Scientists and environmental groups warn that One Lake would be devastating for the map turtle, flooding beaches the species depends on for nest-building and wiping out food sources along the Pearl’s riverbed. Critics also say the project could have far-reaching economic impacts beyond Jackson, threatening tourism and other industries downstream.

But the map turtle’s new threatened species status opens One Lake up to legal challenges, creating an opportunity for opponents to fight the project in court.

“We will do whatever is possible to ensure that the Pearl River map turtle receives the protections it is entitled to under the Endangered Species Act,” said Lindsay Reeves, a senior attorney at the Center for Biological Diversity, a nonprofit organization working to protect endangered species.

The center and other organizations, including the New Orleans-based water advocacy group Healthy Gulf, have indicated they will take legal action if the Corps moves ahead with its current One Lake plan. The agency has tapped the project as its likely choice for flood mitigation in Jackson and expects to issue a formal decision by the end of the year.

Flood Relief at a Cost

One Lake has been a polarizing topic in Jackson and its suburbs for more than a decade.

During that time, various forms of the project have been touted as the answer to persistent, destructive flooding from the Pearl River, which flanks the capital city and flows through Mississippi and Louisiana before emptying into the Mississippi Sound.

In recent years, Pearl River flood waters have forced mass evacuations across Jackson and caused widespread property and infrastructure damage.

The Corps’ new One Lake plan would follow the river’s natural bends, creating a narrow, winding reservoir stretching from northeast Jackson to the south end of the city.

By widening the Pearl’s channel and allowing more water to flow downstream at lower levels, the agency hopes to reduce flood risk to nearby properties while providing recreation and development opportunities around a new lake. The updated project would extend some flood protection to about 773 structures in the Jackson metro area, according to Corps estimates.

Despite these projected benefits, the Corps acknowledges that building a lake along the Pearl would “likely adversely affect” the map turtle and other protected species on the waterway.

Separately, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has warned that the project could diminish the turtle’s resiliency in sections of the river, stating in its threatened species listing that “up to 170 individual Pearl River map turtles could be impacted by the construction of the One Lake Project.”

“When you are dealing with a federally threatened species, 170 is … a big loss,” said Will Selman, a biologist and professor at Millsaps College in Jackson who studies Pearl River map turtles extensively as part of his field research. “It certainly won’t help their conservation status.”

Other species, including Ringed Sawback turtles and Gulf sturgeon, could also be affected.

Under the Endangered Species Act, the Corps must consult with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service before moving forward with an engineering project that could jeopardize the map turtle. While the law normally prohibits the “take” of a protected species—defined as any form of harm—exceptions exist for federally sanctioned infrastructure projects like highways or dams.

“In this situation, the Corps is trying to build a flood-risk management project, and so the take of these turtles would be incidental to a lawfully regulated activity,” said David Felder, a supervisory fish and wildlife biologist at Fish and Wildlife’s Mississippi Ecological Services Field Office.

As part of One Lake’s consultation process, Felder said his agency is developing “reasonable and prudent” measures that the Corps must adopt to minimize impacts on listed species in the project area. Those measures, which may include new habitat construction or relocating map turtles to other parts of the river, will be part of a biological opinion on One Lake expected sometime this fall.

Environmental groups and independent scientists say that’s not enough. Many have noted that dredging the Pearl River would submerge vital portions of the turtle’s habitat, including sandy shoals along the waterway that the species relies on for nesting, basking and other critical functions.

“Pearl maps were found throughout the upstream, downstream, within the section where the lake would be created … that’s their home,” Selman said. “One turtle may live its entire lifetime in this one bend of the river.”

Others point out that damming the Pearl near Jackson would alter the river’s natural flow, raising sediment levels downstream and smothering mollusks and other wildlife essential to the turtle’s diet.

“We’ve seen nationwide what it looks like to impound rivers … and it’s really destructive,” said Reeves. “I can’t conceive of a plan that would both achieve a lake [along the Pearl] and would not harm the species that live there.”

Reeves’ organization supports an alternative flood-control strategy for Jackson that would make no structural changes to the Pearl River. The plan calls for elevating homes in flood-prone areas and voluntary property buyouts for residents open to relocating.

The Battle Ahead

The Pearl River map turtle’s new protections could make One Lake susceptible to legal challenges, but groups contemplating litigation still face an uphill battle. While the Endangered Species Act prohibits actions that would threaten a protected species or its habitat, those two components aren’t given equal weight under the law, legal experts say.

The statute “does a better job at protecting species—like just the critter itself—than the habitat that it depends on,” said Kristina Alexander, an environmental law expert and the endowed chair for marine policy and law at Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi Harte Research Institute for Gulf of Mexico Studies. “That’s not really how the act is supposed to function. But in practice, sometimes that’s how it nets out.”

To effectively challenge One Lake under the Endangered Species Act, environmental groups would have to draw a clear connection between the project’s toll on the map turtle’s habitat and the consequences for the species itself, Alexander said.

Furthermore, plaintiffs would have to demonstrate that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service failed to consider all relevant science and information when crafting its biological opinion on the project.

“They [would] need to show that the Fish and Wildlife Service disregarded the mandate of the Endangered Species Act—which is to conserve species—and that their decisions weren’t based on sound science,” Alexander said.

Endangered Species Act protections have helped foil large-scale engineering projects in the past. In 1978, the Supreme Court halted construction of a dam on the Little Tennessee River, ruling that the project would imperil a protected fish species by destroying its habitat.

The case marked the court’s first interpretation of the Endangered Species Act, passed five years earlier, and became a reference point for future cases involving the statute.

The decision in Tennessee Valley Authority v. Hill and subsequent environmental cases should offer some hope for organizations looking to fight One Lake in court, Alexander said.

“The Pearl River map turtle has no other place to live,” she said. “The plaintiffs have a higher hill to climb, but there are many, many lawsuits where the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has been found not to have followed the best science available in making its decisions.”

In the case of One Lake, Alexander is confident the project’s impact on the map turtle’s behaviors and habitat would constitute a clear Endangered Species Act violation.

“I think that it’s very clear that if you drown turtles, then they are less likely to survive,” she said.

Selman worries the map turtle’s protections may not be enough to stop the Corps’ plan on their own. Though the species could form the centerpiece of lawsuits moving forward, Selman believes sustained opposition from communities along the Pearl River will ultimately decide One Lake’s fate.

“A turtle is not going to stop this project from happening,” he said. “It’s going to be people that stop the project from happening.”

This story is a product of the Mississippi River Basin Ag & Water Desk, an independent reporting network based at the University of Missouri in partnership with Report for America, with major funding from the Walton Family Foundation.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,

David Sassoon

Founder and Publisher

Vernon Loeb

Executive Editor

Share this article

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.