On Meeker Avenue in Brooklyn, How Environmental Activism Plays Out in the Neighborhood

Hazardous: First in a series about the ongoing struggle to clean up Brooklyn’s Superfund sites.

The sign-in sheet stared back at me. I have been attending meetings in Brooklyn for the Meeker Avenue Plume Community Advisory Group since it was founded more than a year ago, and I still never know if I should write my name down or not.

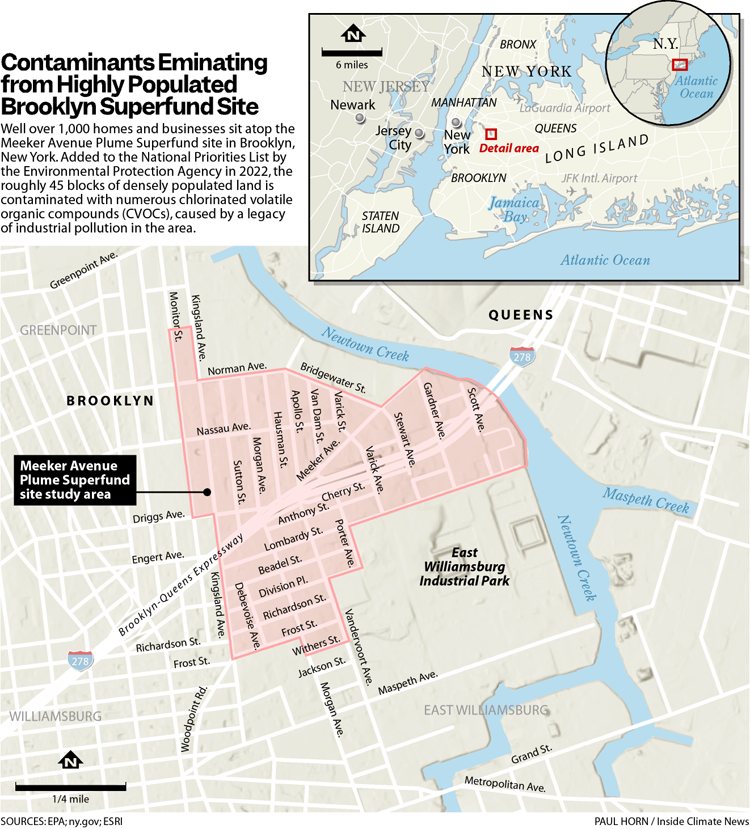

Politicians and environmental agency officials attend these monthly meetings to weigh in on the Meeker Avenue Plume, a federal Superfund site which stretches roughly 45 blocks in parts of Greenpoint and East Williamsburg in Brooklyn. These are some of the people who have declined my requests for interviews about the hazardous vapors potentially seeping into more than 1,000 homes and hundreds of businesses in the area from the underground plume.

I scribbled my name down on the form because who was I kidding? Wearing an N95 mask wasn’t going to make me anonymous. A few officials from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, who are overseeing the cleanup of the plume, stood fanned around the foldout chairs that would soon be occupied by meeting regulars: the man who always brings up the number of community meetings he attends; the other local journalist; and four leaders of the Meeker Avenue Plume Community Advisory Group: Heidi Vanderlee, Lisa Bloodgood, Lael Goodman and Natalie Vichnevsky.

Explore the latest news about what’s at stake for the climate during this election season.

These groups, better known as CAGs, are created by community members to act as volunteer liaisons between residents—those who live in or around some of the most hazardous places in the country—and the EPA, state environmental regulatory agencies and other organizations that are involved in the cleanup of these sites.

I’ve spent nearly three years (and the majority of my 30s) covering the Meeker Avenue Plume and the other two federal Superfund sites in Brooklyn, Newtown Creek and Gowanus, and it’s been at these CAG meetings that I’ve come to understand how environmental activism plays out at the neighborhood level. I’ve also learned from the CAGs about how to be a New Yorker: resilient, brazen and self-assured. These are the same characteristics needed to ensure a Superfund site is cleaned up.

Vanderlee, Bloodgood, Goodman and Vichnevsky have spent many hours to start the Meeker Avenue CAG and to make this meeting, and almost a dozen others, happen.

Tonight there was a good size crowd for a Wednesday evening in September.

In my futile attempt to remain anonymous, I sat down in the second row and started checking texts on my phone. Mid-sentence in a text to my mom, letting her know I had made it to the meeting safely, Vanderlee turned around in her seat to chat with me about my favorite subject aside from Superfund sites: B horror movies.

“Have you seen a movie called ‘Street Trash’?,” she asked. “I don’t recommend it because it’s problematic, but you can see what Greenpoint looked like in the ’80s.”

I hadn’t, but a quick Google search let me know that “Street Trash” is about a local liquor store owner who finds a case of old booze and starts selling it to people who are unhoused.

Unfortunately, and unbeknownst to the liquor store owner, the booze is toxic and causes anyone who drinks it to melt.

In 1987, when the movie came out, Greenpoint was dealing with the discovery of one of America’s biggest oil spills. The monitoring of that spill also opened up a whole other can of worms.

Environmental officials found that legacy contamination left by dry cleaners and manufacturers had seeped into some of the neighborhood’s soil and groundwater and were traveling underground in a chemical plume. Not only can these contaminants still move, all these years later, they can rise upwards, through cracks in building foundations and basements, and into a building’s indoor air through a phenomenon called soil vapor intrusion. Basements like the one where the CAG meetings are usually held, the basement of St. Nicks Alliance on Kingsland Avenue.

Lucky for me and the other CAG meeting attendees, St. Nicks Alliance is outside of the plume’s current boundaries.

“Thanks, everyone, for coming,” said Natalie Vichnevsky, pushing her black, round glasses up the bridge of her nose. “Before EPA gets going with the presentation, we just want to do a quick round of introductions.”

I glanced at the time on my phone: 6 p.m. Vichnevsky’s always right on time.

“I’m part of the steering committee for the CAG.”

“I also live right off the edge of the plume border.” With that, Vichnevsky smoothed her cotton, long-sleeved shirt with black-and-white horizontal stripes and sat down.

Vanderlee, whose long, brown hair was twisted loosely in a bun on top of her head, bobbed her head in solidarity.

“I’m Heidi Vanderlee. I am also a steering committee member of the CAG and I have lived here for a while. I live right in the middle of the plume, so, yeah, nice to meet you, if I haven’t met you yet.”

Vanderlee has rented apartments on the plume since 2008. She’s told me in the past that she found out about the problem from the media. (It wasn’t me.) We’ve gotten to know each other since she helped start the CAG.

Each person in the room had their moment to introduce themselves and their relationship with the Meeker Avenue Plume. Most people in attendance lived in the neighborhood. I don’t, which always makes me feel like a poser when I attend these meetings. Greenpoint is where I go for cocktails and pierogies, but I live in Queens.

While my apartment has its own issues (poor cell reception and residents who don’t know how to recycle), I don’t have to worry about breathing in trichloroethylene (TCE) and tetrachloroethylene (PCE), two chemicals found at high levels in the indoor air of some apartments in the plume. The EPA, which routinely gives presentations at the CAG meetings, has linked these chemicals to cancers and birth defects.

“There’s no penalty or repercussion for a contaminated property, not right now, anyway.”

— Lisa Bloodgood, Meeker Avenue Plume Community Advisory Group

There’s a sense of urgency because of the soil vapor intrusion issues and the lack of interest by landlords to get their buildings tested—for free—by the EPA.

“There’s some people who basically heard, ‘Thing in my basement. Poison,’ and then they think, ‘Property value. Down.’ And that’s it. That’s where the talk stops,” Vanderlee said during one of our routine follow-up calls.

The property owners think that if they allow the EPA to test their buildings for soil vapor intrusion, they’ll be held liable for any health problems their tenants may face because of the indoor air pollution.

Bloodgood, who works in Greenpoint on the plume and lives in nearby Williamsburg, said she encourages landlords to test their buildings so they can find out if there’s a problem and then they can fix it if there is.

“There’s no penalty or repercussion for a contaminated property, not right now, anyway,” she said. “You’re already on a Superfund footprint. That’s easy information to find. And if you’re trying to sell your house and you haven’t taken a step to address it, that’s more of a problem for you than if you do try and address it.”

In a nutshell, her message to landlords is: You have nothing to lose.

Testing is crucial for determining the scope of the vapor intrusion problems in the neighborhood, Goodman said.

“I think it’s important that the EPA has a better understanding of the community that they’re working with,” she added.

Vanderlee, Bloodgood, Goodman and Vichnevsky have coordinated their efforts to make people aware of what is going on.

They became the A-Team of environmental activism in the neighborhood, pooling skills from their professional backgrounds. Vanderlee is in marketing. Bloodgood’s a former environmental advisor for New York City Councilmember Stephen Levin, whose district included two of the city’s other Superfund sites: Newtown Creek and Gowanus; Goodman is the director of environmental programs with the nonprofit North Brooklyn Neighbors. And Vichnevsky works with Evergreen, a nonprofit that supports industrial manufacturing businesses in North Brooklyn. Evergreen is also housed in the same building as St. Nicks Alliance.

Combined they have more than 20 years of experience in environmental activism. It’s this experience that’s allowed them to take stock of the situation they’re in, as Greenpoint residents and stewards of the CAG.

They’ve been able to learn from members of other New York City CAGs, like the one in Gowanus, on what to do (hire a facilitator: check) and what not to do (don’t let special interests run the show).

“I can talk about all this stuff now in a way that I never imagined,” Vanderlee said.

I remember the first Meeker Avenue CAG meeting I attended and the walk to get there across the Pulaski Bridge from my neighborhood in Queens. I was running a little late and had to stand by while the bridge opened up to let trash barges through en route to New Jersey.

The CAG meetings really helped me create my geography of familiarity. I’m now guided by this map of habit that takes me from my apartment to St. Nicks Alliance and the weeknight karaoke that sometimes follows.

When I moved to New York City about seven years ago, I hadn’t heard of Peter Pan donuts (the current employer of MJ from Marvel’s Spider-Man) or the recently closed Saint Vitus Bar—or Newtown Creek, the Superfund site that marks one of the major borders between Brooklyn and Queens.

But Greenpoint gradually took on more significance in my life: My partner proposed to me at WNYC Transmitter Park, I found a cake I actually like and learned the joys of karaoking past midnight.

I grew up in Seguin, Texas, and covering these CAG meetings helped show me how New Yorkers relate to one another, work out neighborhood problems and interact with seemingly faceless institutions.

These institutions include the media. When I started covering the environment and the climate crisis years ago, I had this expectation that the people I spoke with for stories—the residents, the environmental agencies, the politicians, the city departments and my fellow journalists—would be a little more kumbaya and a lot less competitive. Those early days, I tried to channel a granola eating, Birkenstock wearing, Dave Matthews Band listening childhood camp counselor I admired so much. Then I started covering Brooklyn.

“I’m Jordan Gass-Poore’. I’m a journalist,” I said at the meeting. “Since Lael ran into me the other day, I think you can say I hang out a lot in the neighborhood.”

Introductions continued as chairs squeaked, people coughed, the air conditioning pumped in the background and the elevator dinged, signaling the arrival of a local politician’s aide.

“We’re going to turn it over to the EPA now,” Vanderlee said.

John Brennan, the EPA’s remedial project manager for the Meeker Avenue Plume, pointed to an image in his slideshow on the screen, a Mondrian-esque map that showed the plume’s boundaries.

The EPA designated the Meeker Avenue Plume a Superfund site in March 2022. It was around the time wearing a mask on the G train fell out of fashion and the weather in New York City still warranted a cardigan.

“Keep in mind, just because we’ve got these blue lines doesn’t mean that we’re bound by these blue lines,” he said. “Just because you live the street over or maybe, you know, one street in the other direction doesn’t mean you can’t reach out to EPA and find out if your home is eligible for testing. By the same token, just because you live inside this area doesn’t mean you’re necessarily at risk.”

Greenpoint residents, some of whom sat around me, are now split between those who live on the plume and those who don’t. But any day now, that line could change.

I reviewed my notes from previous CAG meetings, re-reading that the EPA is building on the work of the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, which already identified six former businesses as being responsible for the site’s contamination.

Between 2008 and 2022, the DEC sampled the indoor air of 166 properties. In 27, the agency installed equipment to remove the chemicals that continue to run. There came a point where the DEC couldn’t clean up the plume on its own. So it asked the EPA for help.

As of October, the EPA has sampled the indoor air of 47 properties. So far, the agency has only needed to install equipment to clean up the chemicals once (with another property soon to be added). But at each CAG meeting, the number of homes and businesses the agency has tested continue to go up. That’s a good thing.

Brennan reminded CAG attendees that the EPA will continue to test people’s indoor air in December during what’s called “the heating season.” These are the winter months when doors and windows are usually shut and the heat’s running.

“And then we’ll be doing testing again at the beginning of next year,” he said.

As long as the area remains a Superfund site, the CAG will continue to hold meetings where the EPA shares some of its data with the public. This is huge. Since the very first CAG meeting, tenants and landlords have raised concerns about data privacy and transparency, weighing the balance between the public’s right to know and a homeowner’s ability to sell. Some people also don’t trust the government and don’t want officials in their home.

Data tells an important story about the past, present and future of Greenpoint and East Williamsburg. It was data that determined the Meeker Avenue Plume should be a Superfund site, and it’s data that will determine whether or not the area is safe. It’s data that lets residents make informed choices that could impact their health.

It’s been more than two years since the plume was designated a Superfund site. In that time, the CAG has created a website, hosts regular meetings and made public comments on the EPA’s proposed cleanup plan for the site, which will be discussed at an upcoming CAG meeting.

“We have lots of comments, actually,” said Vanderlee, including a recommendation on setting stricter standards for indoor air contamination. “I see it as us being able to try and be as involved as possible and control this as much as possible in terms of how it affects the neighborhood.”

The Meeker Avenue Plume is a particularly problematic Superfund site because contaminants are going directly into people’s homes and businesses, Goodman said.

“It can be a huge part of people’s lives, whether they know it or not,” she said.

In part two of Hazardous, the Gowanus CAG has spent decades trying to get the notorious Gowanus Canal Superfund site cleaned up. Plans by the EPA have stalled and climate change threatens to impact the progress that’s been made, all while dozens of new buildings are going up along the contaminated waterway in one of the biggest residential rezoning projects in modern New York City history.

The project was produced in partnership with the McGraw Center for Business Journalism at the Newmark Graduate School of Journalism in New York.

Jordan Gass-Poore’ is an award-winning independent podcast producer and investigative journalist based in New York City. Currently, Gass-Poore’ is the creator and host of Hazard NJ, a limited-series podcast about the impacts of climate change on hazardous Superfund sites in New Jersey. This podcast is in collaboration with NJ Spotlight News/NJ PBS.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,

David Sassoon

Founder and Publisher

Vernon Loeb

Executive Editor

Share this article

- Republish

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.