After Decades Of Oil Drilling On Their Land, Indigenous Waorani Group Fights New Industry Expansions In Ecuador

After 50 years of expanding oil operations in its Amazonian region, Ecuador will close the door on crude extraction in three oil fields that are home to Indigenous communities, including one of the country’s uncontacted groups.

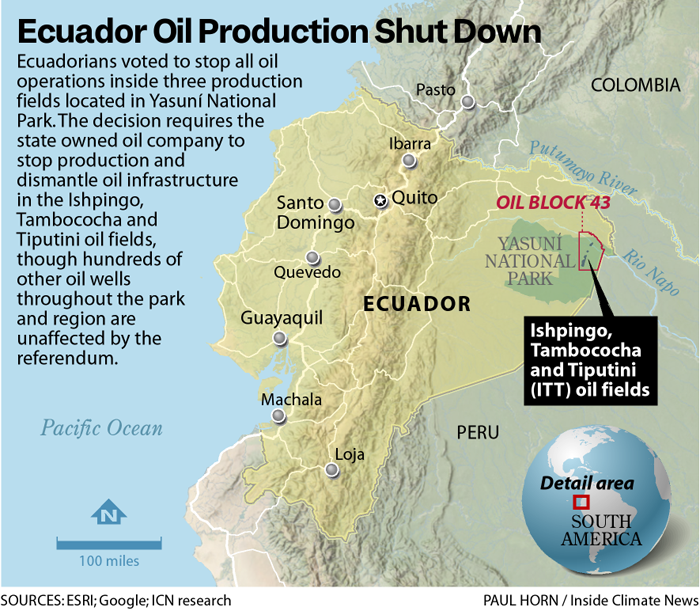

The reversal in policy for the oil-exporting nation was sealed when 59 percent of voters chose in an Aug. 20 nationwide referendum to shut down operations inside the Ishpingo, Tambococha and Tiputini oil fields located inside Yasuní National Park. The government will have 365 working days to comply with the referendum, which includes a requirement for environmental remediation.

The so-called ITT fields, located inside Ecuador’s Oil Block 43, contain a fraction of the hundreds of oil wells that will remain in operation throughout Yasuní and the greater Ecuadorian Amazon region. The ITT fields produce about 54,800 barrels of oil per day; for reference, the United States, which is the biggest buyer of Ecuadorian crude, consumes over 20 million barrels of oil per day.

Ecuadorian President Guillermo Lasso and the state-run oil company Petroecuador released statements saying Ecuador would comply with the results after the minister of energy and mines initially said Ecuador would continue with oil production in the ITT fields despite the outcome of the referendum. In the runup to the election, Petroecuador and pro-oil industry groups argued that stopping production in the ITT fields would cost Ecuador nearly $14 billion, imperil economic growth and cause job loss. The Orellana province where the ITT fields are located was one of only two provinces in the nation that voted “no” to the referendum.

The vote to halt and dismantle production in the ITT fields was widely acclaimed by environmentalists as a victory for the climate and nature. Yasuní National Park is one of the most biologically rich places on the planet and keeping the remaining ITT oil in the ground has been estimated to prevent a total of 410 million metric tons of planet-warming gas from being released.

Yasuní’s rainforest is home to endemic species unique to that area as well as endangered and threatened species like the jaguar, pink dolphins and giant otter. Oil operations in the park have been ongoing for decades and are responsible for large-scale deforestation and over 1,500 oil spills, among other ecological injuries.

The outcome of last week’s referendum holds even greater implications for local Indigenous communities whose families have inhabited the region for over 12,000 years.

Members of one grassroots community, the Baihuaeri of Bameno, announced on Monday that they have convened meetings with neighboring groups to collectively defend other parts of Yasuní which remain under threat from encroaching oil operations. The Baihuaeri are an autonomous clan of Indigenous Waorani peoples whose ancestral territory includes the southern part of the ITT fields.

Their message, released on Monday, thanked Ecuadorians who voted “yes to Yasuní” and said that the Baihuaeri are worried about expanding operations in at least six other oil blocks (numbers 66, 55, 14, 17, 16 and 31) that affect them and other Waorani peoples, including other recently contacted communities and three uncontacted groups. Uncontacted Indigenous peoples are also referred to by the technical term “Indigenous peoples living in voluntary isolation.” It is unclear why the referendum, which was pursued by the Ecuadorian nonprofit group YASunidos in 2013, did not include oil fields inside oil blocks beyond Block 43.

graphic — bigger map

The Baihuaeri are spearheading efforts to bring affected communities together to agree on clear boundaries to stop the expansion of oil operations throughout Yasuní and demand that the government stop sending oil companies into their territories and recognize their land rights.

Ecuador’s constitution and international treaties affirm Indigenous peoples’ rights to their ancestral lands as well as the right to be consulted about activities that could affect them. In Ecuador, however, those rights have often been in tension with other laws allowing extractive activities to go forward if they are in the “national interest.”

“We have heard pretty words from governments and world leaders about the need to stop destroying the Amazon Rainforest to mitigate climate change. We want those words to be a reality,” the Baihuaeri wrote.

Penti Baihua, a traditional Baihuaeri leader, said his Bameno community wants to form alliances with neighboring Waorani communities in order to protect the greatest amount of forest possible. He has been organizing gatherings with other community leaders to discuss the situation of the uncontacted peoples in Yasuní, the encroaching oil companies and their visions for the future.

“We need to set clear boundaries to stop the expansion of oil activities in order to protect our living forest for our children and grandchildren, respect the families who live in isolation, avoid conflicts, and allow everyone to live in peace and tranquility,” the Baihuaeri statement said.

Reaching a universal agreement will have obstacles. Unlike some other Indigenous groups, Waorani peoples do not identify as one nation with a single leader. Rather, they historically have been self-governed at the family and community level.

Prior to the Aug. 20 referendum, at least one Waorani community opposed cessation of oil operations inside the ITT fields, citing the education, healthcare and other services the oil companies provide to their Kawymeno community.

It is unclear whether Petroecuador will continue to fund those services now that operations in the ITT fields will shut down. Typically, governments are responsible for providing those types of public services to citizens.

The Baihuaeri, in their statement, included a message to communities that believe there will be no jobs, education or healthcare without oil operations.

“The oil companies always contaminate, make noise and damage the forest. The animals need a large forest in order to live and reproduce,” the Baihuaeri wrote. “It is important to remember what our grandfathers and grandmothers taught us, and to think about how future generations will live.”

The statement also spotlighted the plight of Ecuador’s three uncontacted Waorani family groups.

One of those groups, the Dugakeri, have been relatively insulated from outsiders’ intrusions into their territory due to the remoteness of where they live. But the group is known to migrate through Oil Block 43, which houses the ITT blocks, and neighboring Oil Block 31. The Baihuaeri said they fear that if new oil operations continue to expand in those areas, the Dugakeri’s future would be afflicted with displacement and violence, much like the two other uncontacted groups, the Tagaeri and Taromenane, are now.

Oil operations and colonization have heavily impacted and displaced the Tagaeri and Taromenane, who in response have violently defended their territory and isolated status by spearing any outsiders entering their lands.

The Tagaeri and Taromenane have also been the victims of deadly attacks, including three mass murder events in 2003, 2006 and 2013. The Baihuaeri warned that if oil operations continue to advance, the violence involving the Tagaeri and Taromenane will increase.

The Dugakeri, Tagaeri and Taromenane are widely considered to be the last remaining uncontacted Waorani groups in Ecuador. All Waorani peoples had lived isolated in the Ecuadorian Amazon region until 1958 when American missionaries with the Summer Institute of Linguistics began the first wave of a campaign called “Operation Auca,” aimed at contacting and evangelizing Waorani people. The term Auca is a pejorative term meaning “savages.”

The second wave of that campaign took off in the 1970s when the American oil company Texaco encouraged the missionaries to accelerate and expand their operations into areas where the company wanted to operate. The aim was to clear Waorani people from their land so drilling could move forward. In her landmark 1991 book “Amazon Crude” and later writings, Judith Kimerling cataloged this history, including statements by U.S. missionaries who recounted how Texaco gave the missionaries use of company helicopters.

In the book “The ‘Inside’ Auca Story,” missionary Catherine Peeke is quoted speaking about the alliance between oil companies and the missionaries. At one point in the book, Peeke describes the missionaries’ use of Texaco’s helicopters, which she refers to as “this thing”:

This thing costs $200-300 an hour to run; and it was a three-hour operation—besides the four high-priced employees! The oil people, in turn, are more than willing to do what they can for our operation, since we have almost cleared their whole concession of Aucas. They assure us that they aren’t just being generous!

The missionaries’ campaign did not reach all Waorani people, and some who were taken to the missionaries’ “Christian protectorate” later returned to their ancestral territories. Still, the campaign was successful at opening up large swaths of Waorani lands to oil operations, and today those areas are heavily polluted, deforested and overrun with oil infrastructure and colonization.

Beyond the displacements and contamination brought on by missionaries and oil operations, Waorani families have lost control over their territories in other ways. In 1979, the Ecuadorian government created Yasuní National Park out of ancestral Waorani lands without consulting or informing the affected communities. Since then, hundreds of wells, including those in the ITT block, have been installed on the legal basis that the oil operations are in the “national interest.”

Now, the Baihuaeri say they want Ecuadorians and the wider world to know that they and other Waorani communities are engaged in their own process to save what remains of Yasuní, defend their territories and protect their isolated relatives. Their statement invites “those who say ‘Yes to Yasuní” to support their efforts.

“Our message to everyone is that we want to live and protect our rainforest territory, Ome, for future generations,” they wrote. “We have our own voices, and we want to be heard and respected.”

How the Yasuni ITT Initiative Came Together

Last week’s vote on oil operations in the ITT fields has been more than 15 years in the making.

The idea that Ecuador should forgo extracting some of its oil in exchange for international financial support from wealthy countries was raised in December 2006 by the economist and incoming Minister of Energy and Mines, Alberto Acosta.

Acosta’s proposal was embraced by his boss, the newly elected leftist president Rafael Correa. The following year, Correa announced at the United Nations that Ecuador was seeking to raise funding commensurate to half of the value of 846 million barrels of unexploited oil the the Ishpingo, Tambococha and Tiputini oil fields (about $3.6 billion as of 2007). By 2013, with only a small fraction of the funds raised, Correa declared that Ecuador would move forward with operations in the ITT fields. “The world has failed us,” Correa proclaimed.

In the months that followed, Correa’s administration took two steps to advance oil operations within the ITT fields. He asked the Ecuadorian congress to declare that oil operations in the ITT fields were in the national interest, a constitutional prerequisite for drilling inside a national park. And, his administration changed official maps that had shown the presence of isolated family groups living in and around the ITT oil fields. The nation’s constitution prohibits “all forms of extractive activities” on the territories of peoples living in voluntary isolation, and so the change in mapping was widely seen as a bureaucratic maneuver to circumvent the legal protections for the Dugakeri, Tagaeri and Taromenane.

In August 2013, the non-governmental organization YASunidos launched a campaign to gather enough signatures to force a nationwide referendum on the question of whether Ecuador should leave the oil under the ITT fields in the ground into perpetuity. By 2015, the activists amassed over 750,000 signatures, the majority of which were invalidated by the Correa administration. Nearly a decade and multiple legal battles later, Ecuador’s constitutional court ruled on May 9 that YASunidos’ had enough valid signatures to force the referendum.

As that litigation was unfolding, the Correa administration forged ahead with operations inside the ITT fields, which began producing oil in 2016.

Natalia Greene, an Ecuadorian political scientist and founding member of YASunidos, said last week’s vote “sent a very powerful message” that the people of Ecuador were voting for life—both for the rights of nature and for the Indigenous people living in Yasuní. In 2008, Ecuador became the first country to recognize the rights of nature in its constitution. Greene said she sees the outcome of the August 20 referendum as the nation’s affirmation of the recognition that nature and all its constituent parts have inherent rights to life, among other things. Humans, she emphasized, are also a part of nature.

Greene, who is now an executive committee member of the Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature, also rebutted the implication made by Petroecuador and pro-oil groups that oil extraction is needed to alleviate poverty in Ecuador.

“We’ve had 50 years of oil exploitation and we’re still a very poor country,” she said. “Exploitation of nonrenewable resources has a structure where few people and foreign companies win a lot of money, a few people get poor-paying jobs and our resources are exported. The social and environmental costs are never taken into account.”

Chocó Andino Referendum

The ITT vote was one of two referendums Ecuadorians decided last week.

About 68 percent of Quito’s voters also approved regional plebiscite questions to block mining in the forests and Andean mountains of the Chocó Andino de Pichincha Biosphere Reserve located just outside the capital city.

The Chocó Andino referendum, led by the non-profit organization Quito Sin Minera, will affect an area slightly smaller than the state of Rhode Island.

The outcome of the vote means that the 12 exploratory mining concessions for copper and gold cannot progress to extractive licensing and no future mining licenses can be issued.

The Chocó Andino region is rich in both cultural and ecological diversity. It has hundreds of archaeological sites and is home to endangered species including the spectacled bear, as well as around 10,000 plant species and hundreds of species of mammals, reptiles, birds and amphibians. As one of Ecuador’s seven United Nations’ Biosphere Reserves, it is also an epicenter for pioneering research on sustainable living and economies.

Greene said the Chocó Andino referendum should remind people that copper, gold and other materials desired by developed countries for the transition to cleaner energy sources often come from biodiverse places.

“There’s no fighting climate change without biodiversity and the biggest threat to biodiversity in Ecuador is mining. We need to look at the bigger picture,” she said.

Both the ITT and Chocó Andino referendums were part of snap presidential and congressional elections. Ecuador’s presidential race will be decided on Oct. 15th in a runoff between Luisa Gonzalez, a leftist affiliated with Rafeal Correa, and pro-business candidate Daniel Noboa.

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.