EVs and $9,000 Air Tanks: Iowa First Responders Fear the Dangers—and Costs—of CO2 Pipelines

From outdated equipment and evacuation plans to a lack of personnel and training, some Iowa first responders say they would be unable to safely carry out rescue operations in the case of a major carbon dioxide pipeline rupture. Many Iowans fear such a disaster is increasingly likely as developers, spurred by more than $12 billion in federal incentives, propose to build lengthy CO2 pipelines across the Midwest.

Among the handicaps emergency personnel would face if responding to a rupture is a lack of funding for the kind of equipment they say is necessary to safely navigate the unique threats posed by carbon dioxide pipelines, including CO2 plumes released during a failure that could have an especially large and difficult to detect danger zone.

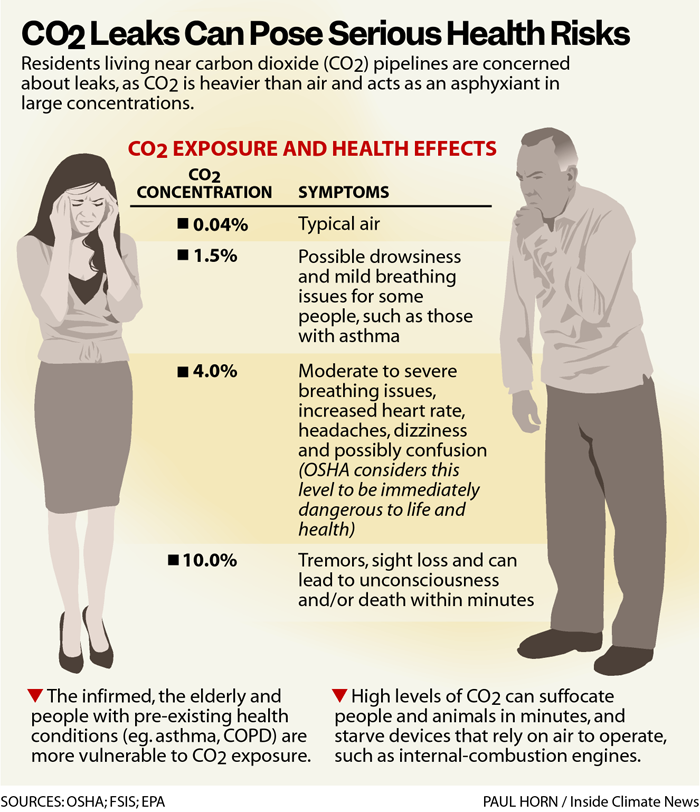

When a carbon dioxide pipeline ruptured in 2020 in Mississippi, it released a massive cloud of the gas that traveled more than a mile into the nearby hamlet of Satartia, sending 45 residents to the hospital and prompting the evacuation of 200 others. That’s because CO2 is heavier than air and acts as an asphyxiant in high concentrations.

Dan Harvey, fire chief for the Gruver Fire Department in Emmet County, Iowa, said it would cost the five fire departments in his county—all of which are run by volunteers—more than $370,000 to upgrade their current air tanks, which can hold about 15-20 minutes-worth of oxygen. That’s not enough time to safely operate in those conditions, Harvey said, but most Iowa fire departments can’t afford to buy the 45-minute air tanks.

“The airpacks alone,” he said, “if you buy them new, those are about $9,280 each.”

Jodi Freet, the emergency response director for Cedar County, Iowa, said that besides larger air tanks, she also wouldn’t feel comfortable sending any of her personnel near a CO2 leak unless they were driving an electric vehicle.

Not only can a high concentration of carbon dioxide suffocate animals and people in a matter of minutes, it can also stall engines that run on gasoline since they, too, require oxygen. First responders at the Satartia incident quickly realized that when some of their own vehicles died as they attempted to rescue others.

“Our fire trucks are all combustion engines,” Freet said. “So if there’s a rupture, and they have to respond, those engines aren’t going to work.”

Other expenses Freet and Harvey said their departments could face include purchasing oxygen monitors to detect spikes in CO2, as well as paying for additional training for staff and educational materials for the public—similar to safety campaigns that taught people to “stop, drop and roll” if their clothes catch fire.

Both Emmet County and Cedar County could soon host large CO2 pipelines if state regulators approve the projects. At least two developers—Summit Carbon Solutions and Wolf Carbon Solutions—are planning to build pipelines that would stretch hundreds to thousands of miles through several Midwest states. And Iowa first responders say their conversations with the companies haven’t resolved just who will pay any additional costs to their departments, which could reach millions of dollars.

That makes officials like Harvey and Freet nervous that Iowa’s already cash-strapped emergency response agencies, many of which rely on volunteers and community fundraising events, could be saddled with those expenses. If that’s the case, Freet said, she doubts her department will be able to respond to a rupture safely and she wouldn’t be willing to risk the lives of her crew.

“I feel horrible having to tell some landowners, ‘We may not be able to come and get you if something happens,’” she said. “That’s a horrible thing to have to think about.”

How Close Is Too Close?

The two CO2 pipelines that would run through Iowa are among three major projects that have been proposed in the Midwest since 2021.

Summit Carbon Solutions proposed a 2,000-mile pipeline from North Dakota to parts of Nebraska and Iowa, which would run through Emmet County. And Wolf Carbon Solutions proposed a 280-mile pipeline between Iowa and Illinois, which would run through Cedar County—although Wolf paused its project in November, saying it will refile its permit application in 2024. A third developer, Navigator CO2 Ventures, had proposed a 1,300-mile pipeline through five Midwest states, including Iowa, but canceled the project in October amid mounting opposition from landowners.

As the projects have moved forward, many community members have questioned whether the proposed routes come too close to their homes and gathering places.

An analysis by Inside Climate News found that some of the proposed routes fall within a couple miles, sometimes less than half a mile, from public schools, assisted living facilities, hospitals and state prisons. Before Navigator canceled its project, its proposed route in Illinois came within just 2,300 feet of the Western Illinois Correctional Center, which houses nearly 1,700 adult inmates who experts say could be a logistical nightmare to evacuate.

It’s hard to say how close is too close, said Ted Schettler, science director of the Science and Environmental Health Network, an environmental and public health advocacy group. Schettler, who holds a medical degree and is very familiarized with carbon dioxide safety issues, said answering that question requires complex computer modeling that takes into account the weather, topography and other factors like how much CO2 was released.

“If we look into the published literature on this, where people have tried to estimate the public health risks associated with these ruptures and plume dispersion, the safety distances that have been estimated range from a very short distance to up to four and a half miles depending on the assumptions in the model that are used to do the risk assessment,” Schettler said.

Some Iowa first responders said that those models for the proposed projects have either not been adequately conducted or the results weren’t made available to them.

Studies also show a large variation in people’s tolerance to high levels of CO2, he added, saying that older people and those with pre-existing conditions, such as heart disease, tend to be the most vulnerable. Some of the symptoms of overexposure, Schettler said, include trouble breathing, increased blood pressure, feelings of confusion or lethargy, seizures and losing consciousness. Death, he said, is also a real possibility if victims aren’t removed from the low-oxygen conditions.

When the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration, the federal agency that regulates construction safety standards for major pipelines, investigated the Satartia rupture, it determined that communities within 2 miles of a rupture could be impacted. PHMSA is currently working on a new rule that would strengthen its safety standards for CO2 pipelines, with plans to finalize it by the end of 2024. But because siting jurisdiction for CO2 pipelines falls to states, the rule won’t directly address the distance issue.

Some counties, such as Story and Shelby counties in Iowa, have passed their own setback ordinances, which restrict how close a CO2 pipeline can be built near homes, schools and other buildings. But Summit sued the counties and won. On Dec. 5, a federal judge ruled that siting authority belongs to the Iowa Utilities Board and ordered the counties not to enforce their statutes.

Summit is also suing Emmet County, where Dan Harvey owns a farm and volunteers as fire chief, after the county passed a similar setback ordinance. That case is still in litigation.

Harvey said Navigator and Summit have their own calculations regarding safe distances from their proposed projects, which they shared with Emmet County. According to Harvey, Navigator determined that anyone within 1,100 feet of its pipeline, if it ruptured in Emmet County, would be in immediate danger without breathing equipment; at 1,800 feet, engines would begin to stall; and within 4,800 feet—just short of a mile—people may experience health issues, including confusion and difficulty breathing.

Summit estimates were far less stringent, Harvey said. The company determined 100 feet as its critical zone, up to 300 feet as causing borderline health problems and everything after as being completely safe.

To see what those distances could mean for a rescue operation, Harvey and one of his colleagues decided to test them against their current 20-minute air tanks. As Harvey video taped, his colleague walked, in full regalia, some 1,300 feet before checking his oxygen gauge.

“He literally had about 5 minutes of air left,” Harvey said.

Summit didn’t reply to questions sent by Inside Climate News or requests for interviews. But the company has said that its pipeline can be built and operated safely.

A spokesperson for Wolf responded to questions about the company’s plume studies by pointing to an article published in April by a local Iowa newspaper, in which emergency management officials from Linn County said that they were “impressed” with Wolf’s safety plan. Wolf also reviewed a dispersion model with Linn County officials, according to the article. Wolf’s website states that the company will be responsible for providing “a public awareness program,” which includes training for emergency responders but doesn’t mention equipment costs.

In a November interview, Jim Mullin, Navigator’s former executive director of carbon utilization, said he believed there was a lot of misinformation spreading among landowners regarding the safety of CO2 pipelines. Mullin said there are already large volumes of CO2 being stored all over Iowa and Illinois, including onsite at ethanol plants, without any major accidents occurring.

“There are facilities that have thousands of tons of CO2 stored on the premises and not a single person walking around with a respirator,” he said.

Complications for Rescue Plans

Harvey, the Emmet County volunteer fire chief, still remembers Iowa’s historic snow storm of 1975 vividly. He now owns his great grandfather’s property, where he farms corn and soybeans on 68 acres of land and where Navigator had hoped to build part of its pipeline.

It snowed 16 inches over three days that week in January, local papers said, with snow drifts reaching upwards of 15 feet high. Winds in excess of 90 miles per hour hurled sheets of snow against fences, trees and buildings, compacting the growing mounds so tightly that they turned to ice.

“By the end of the second day, the beginning of the third day, we finally go out,” Harvey said. “We couldn’t even see the hog unit. It buried it so much, we had to scoop out just enough to get to the roof, and then we fed the pigs through the snow drift for about four or five days.”

Snow drifts are a common occurrence in the plains of the Midwest. In Iowa, where the winds often hit 40 miles per hour in the winter and snowfall of 8 inches or more is common, the drifts can get as hard as concrete.

But when Harvey, during a meeting Navigator hosted for Iowa first responders in September 2023, asked the company’s representatives how they planned to navigate drifts to access a ruptured pipeline, he was met by befuddlement.

“The Navigator expert from Colorado was like, ‘What snow drift?’” Harvey said. “I mean, the room just laughed at him, like you guys ain’t got a clue what you’re even doing.”

Harvey said he encountered similar confusion when he asked how much carbon dioxide would be inside the segments of 8-inch pipeline that Navigator planned to run through his county, forcing his agency to make its own crude estimations based on the volume of the pipes.

Freet, too, said she struggled to obtain information from the pipelines companies, leaving her with little to base her emergency planning on, including when to evacuate people versus ordering them to shelter in place. She said she hopes that Wolf provides her county with plume modeling soon.

“I’ve asked for dispersion studies and I’m not getting those. That’s a key part of our planning, those plume models,” she said. “How can you plan for something when you can’t get the right information for it?”

The situation has left first responders with little faith that the projects can be carried out and operated safely. “I have no problem with pipelines—pipelines are actually one of the most safe ways to transport some of these products,” Freet said. “What scares me is the CO2.”

Share this article

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.