Advocates Celebrate a Legal Win Against US Navy’s Staggering Pollution in the Potomac River. A Lack of Effective Regulation Could Dampen the Spirit

Dean Naujoks was relieved when, earlier this month, the U.S. Naval Support Facility in Dahlgren, Virginia, agreed to get a pollution discharge permit for its weapons testing on the Maryland side of the Potomac River. The Navy has been testing weapons there since World War I.

It took almost seven years of legwork and a lawsuit for Naujoks and other advocates to get the U.S. Navy to acknowledge that the missiles and other projectiles it had been firing into the river could have an impact on the water quality and the aquatic life, including species listed as threatened, such as the Atlantic sturgeon.

“This is just the first good step and a lot would depend on whether the Maryland Department of the Environment include adequate protections in the permit,” said Naujoks, a 58-year old environmental advocate who works at the Potomac Riverkeeper Network, a nonprofit working to protect rivers and habitat in Potomac and Shenandoah watersheds from pollution.

We’re hiring!

Please take a look at the new openings in our newsroom.

See jobsHe remembered telling his colleagues back in 2017 about hearing “scary loud explosions” along the east side of Potomac River in southern Maryland, where he was investigating suspected pollution discharges from the coal-fired power plant near the Nice-Middleton Bridge connecting Maryland’s Charles County and Virginia’s King George County.

The source of the rattling explosions turned out to be the Naval Surface Warfare Center, operating out of the U.S. Naval Support Facility Dahlgren on the western shore of the Potomac River, 53 miles south of Washington, D.C. It was established in 1918 as Dahlgren Naval Proving Ground.

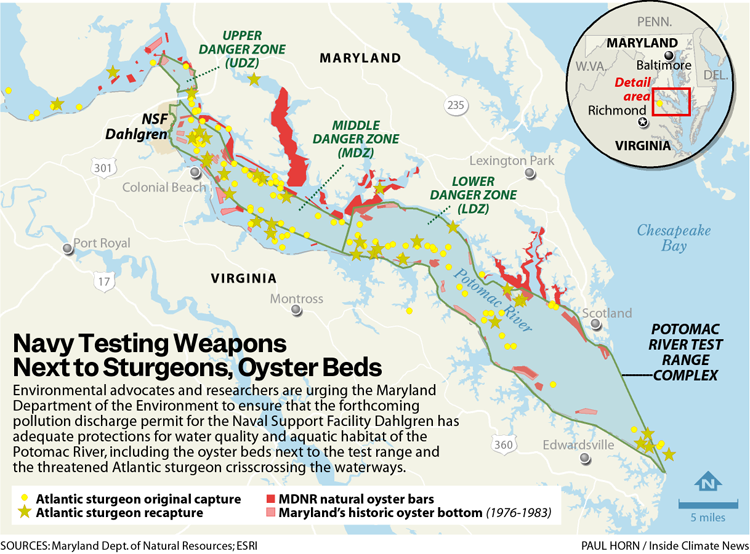

The center has been testing weapons and munitions, including unmanned aerial vehicles and an electromagnetic railgun that fires projectiles using electricity, in the area designated as the Potomac River Test Range. Stretching over 51 miles, from the Nice-Middleton Bridge south into the Chesapeake Bay, the Navy describes the area as “the nation’s largest fully instrumented over-water gun-firing range.”

The Navy’s own estimates, cited in the court filing, suggest it discharged around 33 million pounds of munitions into the Potomac River in the first 90 years of the facility’s operation. Those estimates included 255 tons of various explosives, 225 tons of the toxic heavy metal manganese and 15,000 tons of iron. In addition to carrying out around 200 detonations annually, the Navy fired 4,700 projectiles a year on average into the river using land, sea and airborne platforms such as boats, drones and gun batteries.

From 1918 to 2007 “the Navy fired nearly 70,000 rounds of ammunition per nautical square mile” in a 2.3 square mile area of the testing range called the ‘dense zone’—just downstream of Swan Point, Maryland and Colonial Beach, Virginia,” according to the court document Potomac Riverkeeper and its co-plaintiff, the National Resources Defense Council, submitted, quoting estimates in the Navy’s 2013 Environmental Impact Study (EIS).

The study listed cadmium, chromium, lead, manganese, TNT and cancer-causing ethylbenzene among the 50 metallic and chemical constituents of the projectile fired into the Potomac River for a near century-long operation. “The munitions contain toxic metals, solvents, explosives, and other potentially harmful constituents. The testing takes place on land, in laboratories and in the Potomac River itself,” the plaintiffs said in the court filing.

On Jan. 10, the Navy agreed to apply for a pollution discharge permit from the Maryland Department of the Environment within 30 days under a consent decree approved by the U.S. District Court for Maryland.

A spokesperson for the Navy, Lt. Cmdr. Joe Keiley, said in an emailed response that the Department of the Navy is committed to environmental stewardship and looks forward to working with the Maryland Department of the Environment as they make a permit determination under the Clean Water Act for activities conducted on the Potomac River Test Range.

“The Navy has performed analysis using the best available science to determine the activities conducted on the Potomac River Test Range do not significantly impact human health or the environment,” the spokesperson said, referring to the 2013 EIS.

The Navy has reinitiated the informal consultation with the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), which, Keiley said, had previously concurred that the Navy’s range activities may affect, but are not likely to adversely affect, the proposed and listed species.

In 2012, when the Navy first consulted with NMFS, the Atlantic sturgeon was only proposed to be listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act and has since been placed on the list.

Tyler Frankel, an assistant professor in the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences at the University of Mary Washington, countered the Navy’s assertion. He said that the Navy’s 2013 EIS used computer modeling to predict the transport, deposition and concentration of different munition components including cadmium, chromium, copper, lead, manganese, nickel and zinc along with their potential ecological and human health impacts.

“But there is a distinct lack of field studies designed to confirm these predictions through the collection and analysis of water, sediment, and fish tissue samples from the upper, middle, and lower ‘danger zones’ as designated by the Naval Surface Warfare Center,” he said.

Many of these contaminants have been shown to be concentrated in aquatic food webs, Frankel said, and there is a concern that they may pose a risk to both wildlife and humans through consumption of contaminated organisms. He added that consistent monitoring of both surface waters and sediments should be considered as a key component to ensure safe water quality and minimize ecosystem impacts.

Frankel’s research team is currently designing a study that will look at trace metal and PFAS contamination in the waterways surrounding the Dahlgren facility to test the assumptions of the environmental study the Naval Support Facility provided in 2013.

PFAS—Short for the group of chemicals known as perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances—don’t break down, can stay in the environment for a very long time and can cause serious health risks. A study by the nonprofit Environmental Working Group (EWG), which analyzed the U.S. Department of Defense records, separately found that in 63 military bases in 29 states, 2,805 drinking water wells it tested were contaminated with PFOA and PFOS.

“Our intent is to provide new information that can be used to support and refine plans put forth by the Naval Surface Warfare Center to effectively manage these areas and better inform local populations who utilize these waterways for a variety of purposes,” Frankel added.

Despite the agreement to obtain a pollution discharge permit, the Navy’s weapons testing and discharges will continue while the MDE processes the permit request.

“We made a strategic decision at the beginning of the case that we would not try to shut the Navy’s operations down. We’re not aware of any clear information about the extent of harm caused by the Navy’s activities,” said Bob Dreher, the lead counsel for Potomac Riverkeeper.

He said that despite the staggering volume of materials the Navy discharged into the river, it is not known if it is causing immediate serious harm either to the aquatic ecosystem or to public health. “That’s in part because the Navy has never done any water quality sampling or done any testing of sediments,” Dreher added.

A more important question was whether the discharge permit will require changes in the Navy’s operations, Dreher said. “That’s something that the state of Maryland will have to work to assess whether these discharges are in fact causing significant harm to the aquatic ecosystem.”

Dreher added that in order to write the permit the MDE is required to ensure that the discharges achieve both numeric and narrative water quality standards in the river. “But we don’t know whether that will happen or to what extent it will happen,” he noted.

Jay Apperson, deputy director for the MDE’s office of communications, said in his written remarks that the agency is in communication with the Naval Surface Warfare Center Dahlgren Division to discuss submitting an application for a permit. The MDE has four active industrial pollution discharge permits issued to military installations, he added, including three for naval installations.

“None of them regulate testing over, in or on the water similar to that which is being applied for at Dahlgren,” Apperson said. “We will evaluate an application through the lens of applicable regulations to determine a path forward for a permit. This process will include opportunities for public participation.”

The Potomac River serves as an incredible habitat for endangered species such as the Atlantic sturgeon as well as commercially important finfish such as striped bass, and also provides local communities with subsistence fishing opportunities.

The intense weapons testing on the Potomac River Test Range also caused frequent closures of the waterways, irking watermen and oystermen operating commercial vessels and recreational boaters. Fishing nets routinely caught spent cannon shells, rockets and projectiles in the water near the Naval Surface Warfare Center Dahlgren, the court documents said, leaving those who work on the water concerned about potential harm.

In December 2022, the Navy issued a public notice about its intent to expand the weapons testing range, Naujoks said, which it eventually did. The move prompted advocates and workers to ask the Navy for a meeting to discuss navigational safety and the expansion’s impact on fish and oysters, among other issues. “But the Navy wouldn’t meet with us. Then we filed notice of intent to sue them under the Endangered Species Act and the Clean Water Act,” he said.

Sent out late last January, the letters said that the Navy’s weapons testing and other activities in the Potomac River violated the Endangered Species Act as well as the Clean Water Act, and committed to suing the Navy if it didn’t comply with the statutes within 60 days.

The Navy agreed to meet with the advocates and watermen from Maryland and Virginia after the letters were sent out, Naujoks said. “We had a good meeting with them and we told them to get a Clean Water Act permit that will protect water quality and to undertake sediment and water analysis,” he said. But the Navy refused to get a permit from Maryland or Virginia.

In June, Potomac Riverkeeper and the NRDC jointly sued the Navy in federal court in Maryland and asked the court to direct the Navy to meet its statutory obligations by obtaining a pollution discharge permit from the Maryland Department of the Environment.

The suit alleged that “the Navy never performed any water quality monitoring or sediment sampling to understand the impacts of its weapons testing activities on the Potomac River’s ecosystem and water quality or on public health.” The plaintiffs referenced a 1979 court case in which the Navy was ordered to apply for a discharge permit because of its weapons testing on the island of Vieques, Puerto Rico, which, the plaintiffs argued, settled the Navy’s statutory obligations in similar situations.

But it remains unclear, the advocates said, if the Navy intends to remediate the hundreds of tons of munitions and projectiles accumulating on the riverbed as a result of the last 100 years of weapons testing.

“One of the things that we are looking at is that there’s already a superfund site at Dahlgren naval base. But it’s on land and does not extend into the Potomac River,” said Dreher, the Potomac Riverkeeper’s lead council.

He said the presence of a superfund site at the naval facility pointed to the fact that the Navy has conducted land-based testing of munitions for decades at the base. And as with most sites where the Navy has tested munitions or operated a firing range, there’s contamination from those activities.

“One of the questions we’re exploring is whether the Navy should extend the boundary of the superfund site into the river to embrace any contamination that may be in the riverbed sediments,” Dreher said. “The Navy had not suggested it was willing to do that. But that’s one of the questions I think that we would have to explore.”

In its EIS, the Navy contends that their modeling assumptions are that any munitions fired into the river that reach the riverbed are quickly embedded in the sediment and are rendered inert.

Share this article

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.