Feds Deny Permits for Hydro Projects on Navajo Land, Citing Lack of Consultation With Tribes

Federal officials Thursday denied preliminary permits for multiple pumped storage hydroelectric projects proposed on the Navajo Nation that would have required vast sums of water from limited groundwater aquifers and the declining Colorado River, citing a lack of support from tribal communities.

In the order, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission announced it was implementing a new policy requiring that any project proposed on all tribal land must gain the respective tribe’s consent to be approved, a move that local tribes, opposed to the proposed hydroelectric projects, had been calling for. The decisions pave the way for increased tribal sovereignty in energy-related projects seeking federal approval across the country.

“This is a federal commission acknowledging tribal sovereignty,” George Hardeen, a spokesman for the Navajo Nation president’s office, said. “If a company wants to do business on the Navajo Nation, it, of course, needs to talk to and get the approval of the Navajo Nation. And in the eyes of FERC, that has not yet happened.”

We’re hiring!

Please take a look at the new openings in our newsroom.

See jobsThe Navajo Nation opposed the preliminary permits for the projects through motions to intervene that were submitted by its Department of Justice in 2022 and 2023.

Future projects “should work closely with Tribal stakeholders prior to filing,” to FERC, agency officials wrote in their decision. Before this new policy, the agency had “applied the general policy of granting permits even where issues were raised about potential project impacts without a distinction for projects on Tribal lands opposed by Tribes.”

The decision is the latest setback for the development of hydropower in the U.S. While many see electricity generated by turbines in dams as a key source of renewable energy, a growing body of scientific evidence has found that the reservoirs behind dams are a significant source of carbon emissions—particularly methane, a potent greenhouse gas that’s roughly 80 times more effective at warming the atmosphere than carbon dioxide over 20 years. Hydroelectric dams also block fish from traveling upstream to their spawning grounds, which studies have long shown interfere with their ability to reproduce.

Hydropower dams have had major effects on rivers across the country, including the Colorado River and its tributaries, where four native fish species are now endangered. Such issues have led to the removal of dams along some other river systems.

Pumped storage has been seen by some in the industry as a way to keep hydropower a relevant part of the renewable energy transition, as they don’t always require a river or dam to function. However, environmental problems, and opposition, remain. The projects FERC denied had garnered widespread opposition from the Navajo Nation and Indigenous and environmental groups over the lack of consultation developers offered and the impacts they would have on cultural sites, endangered species and water resources in the area.

In its motion to FERC for a project on the western part of the Navajo Nation near Page, Arizona, the tribe’s Department of Justice wrote that “meaningful consultation” between the company and the tribal government, including chapter administrations and local communities, was “unclear.”

The department also stated that the project might impact the tribe’s water rights or its use of water from the Colorado River system.

“The Navajo Nation’s interests would be directly affected by the outcome of this proceeding,” the department wrote.

Daryn Melvin, a Hopi Tribal member who works as the Grand Canyon manager with the Grand Canyon Trust, which opposed the projects, said the hydro projects are “just the latest in a number of developments that were threatening the area in places that are of particular importance to Native communities.” The impacts of coal and uranium mining persist to this day, he said, and local tribes and environmental groups pushed to find new ways to protect the area, including reform in the FERC permitting process.

In particular, a proposal from Nature and People First to build three pumped storage hydropower projects across 40 linear miles on Black Mesa drew intense scrutiny. Project opponents say the developer never reached out to locals about the project and attempted to pit communities in the area against one another. Representatives of Nature and People First did not respond to a request for comment in time for publication.

Nature and People First states on its website that Chilchinbeto Chapter, where one of the projects on Black Mesa would be located, supported the proposal because it would create jobs and economic opportunities. The company filed resolutions to FERC from the Western Navajo Agency Council and the chapters of Ts’ah Bii Kin and Oljato that supported the project.

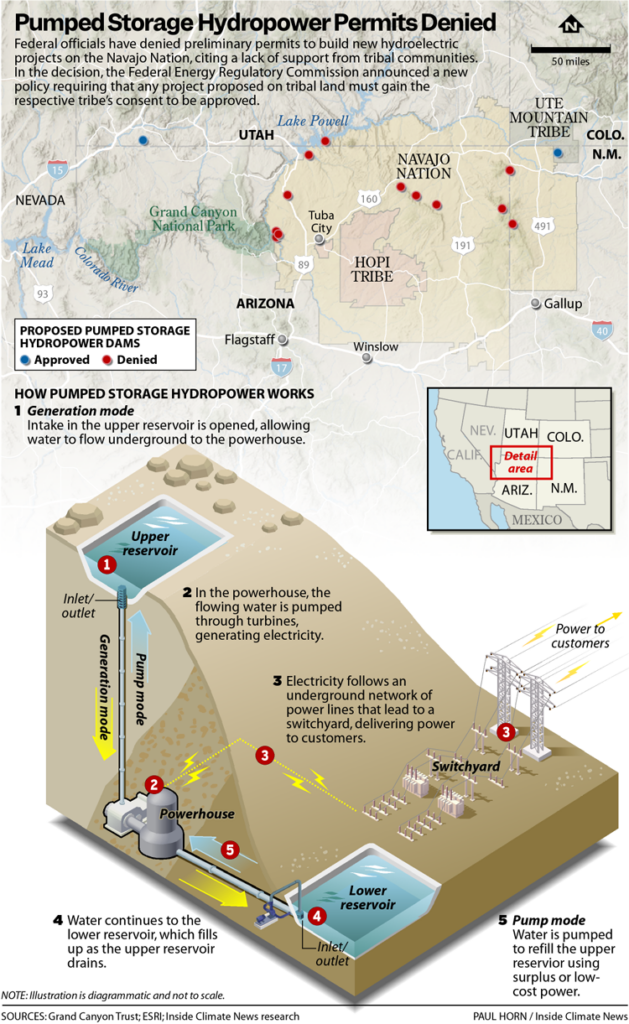

How Pumped Storage Hydropower Works

Over a dozen hydro projects have been proposed in recent years on or near the Navajo Nation for pumped storage—a nearly century-old technology experiencing a surge of interest as the U.S. looks for ways to store energy from renewable sources as it pivots away from fossil fuel-generated electricity.

Pumped storage can help store electricity from wind and solar energy projects for when it is needed and serves as an alternative to utility-scale lithium-ion batteries to bank renewable energy.

The projects use two water reservoirs, one above the other. Water is pumped uphill to the higher reservoir at night when energy costs are low, then sent back down through electricity-generating turbines when energy demand peaks or renewable resources can’t generate electricity, helping to ensure grid stability during system-stressing events like record-hot summers.

But to work, they need certain geographic characteristics, namely a rapid change in elevation over a short distance, leading many of the projects to be proposed in the Mountain West. But they also need water, and a lot of it, which is something lacking in many arid Western communities.

That’s led to pushback across the region as rural residents look to protect their limited ground- and surface water supplies from diversion to pumped storage projects and, potentially, further depletion.

Impacts to Local Water Supplies

If all of the proposed pumped storage projects near the Navajo Nation were built, it would require over 2 million acre feet of water. That’s enough water for over 5 million homes in Arizona and about the same amount of water that federal officials are currently allowing the state to take from the Colorado River in recent drought conditions.

If developed, the projects would further impact flows on the Colorado River and its tributaries, as well as the levels of local aquifers that serve tribal communities. The Hopi Tribe, for example, is completely reliant on the same groundwater sources some of these hydro projects would likely pull from.

“Water scarcity is a simple fact of our region,” said Taylor McKinnon, the Southwest director for the Center for Biological Diversity, which opposed the projects. “Their failure to see that caused them to run headlong into the problem of aridity.”

The Black Mesa projects proposed pulling groundwater from the Coconino aquifer—colloquially known as the C aquifer—which provides the base flows for the Little Colorado River, McKinnon said. “That water comes out of the earth in Blue Springs, and it creates a river,” he said, noting that the flow was critical to an endangered fish. “That river is where the last source population of humpback chub in the world live.”

Thursday’s ruling, for now, puts an end to seven of the proposed projects in the region that would have collectively required around 1.6 million acre feet of water. “This is an agency actually stepping forward and saying, ‘we have the authority to do the right thing and we’re going to do the right thing,’” McKinnon said. “We applaud that.”

The projects have also received pushback from the Hopi Tribe, whose land is adjacent to the Navajo Nation. The projects on Black Mesa not only threatened water sources for the Hopi, but also endangered species and cultural resources, like ancestral trails and shrines, said Stewart B. Koyiyumptewa, tribal historic preservation officer for the tribe.

“We still have a vested interest in our cultural resources left by our ancestors throughout the landscape,” Koyiyumptewa said.

FERC has a policy statement for consulting with federally recognized tribes that preexisted Thursday’s order. While the commission recognizes the government-to-government relationships the U.S. holds with sovereign tribes, how it notifies tribes about proposed projects is dependent on laws, like the National Historic Preservation Act.

For Koyiyumptewa, this leaves tribes cut off from key information about proposals—especially when projects are not on the tribe’s land, but could impact it.

“We weren’t given the opportunity to provide opposition,” he said of the early process for the Black Mesa projects.

Share this article

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.