For an Indigenous woman, discovering an ancestor's remains mixed both trauma and healing

Content warning: This story contains details regarding the human remains of Indigenous people that may be upsetting to readers.

It started with an email.

It was Christmas Eve and I was on holiday, enjoying a few lazy days before the new year with my family in our cabin on the prairies of Treaty 6 territory (an area of land spans the two provinces now known as Alberta and Saskatchewan, Canada).

Andrew Tran, a data reporter from The Washington Post wrote to inform me they had created a searchable human remains database held by The Smithsonian Institution.

“I see that your publication writes about Cree and other Indigenous news and thought you might be interested in going through the database that we just published,” he wrote.

I clicked the link, thinking that I was about to casually read a story on a subject that was not new to me.

It wasn’t until that night when I was in bed and struggling to fall asleep, that I searched the database included in this story. While my husband slept, I found the little box that said, “Search the table.” First, I typed in Fine Day, the name of one of my great-great-grandfathers, and nothing came up.

Then I typed in “Little Poplar,” the name of my other Cree great-great-grandfather –– and instantly got a hit. I flinched in the dark as though from a jump scare. Ka-mîtosis, or Little Poplar, was the grandfather of my grandfather, Alphonse Little Poplar. Ka-mîtosis was a member of the Warrior Society in Chief Sweetgrass’s band of Plains Cree around the time of the Riel Rebellion. A war chief, some folks call him.

War chiefs, sometimes referred to as sub-chiefs, were not actually chiefs, but would be in charge in times of war (My other great-great-grandfather Kamiokisihkwew, or Fine Day, was also a war chief). They were both known for fighting colonialism.

I lay there in the dark, staring at Little Poplar’s name in the glow of my phone screen.

My husband, who is a light sleeper, asked, “What is it?”“They have my ancestor's remains at the Smithsonian,” I said, but he was already drifting off.

I clicked the link to the first page of the file (out of sensitivity, The Washington Post limits each file on its site to the first page. To see the rest of the document, you must contact the Smithsonian.)

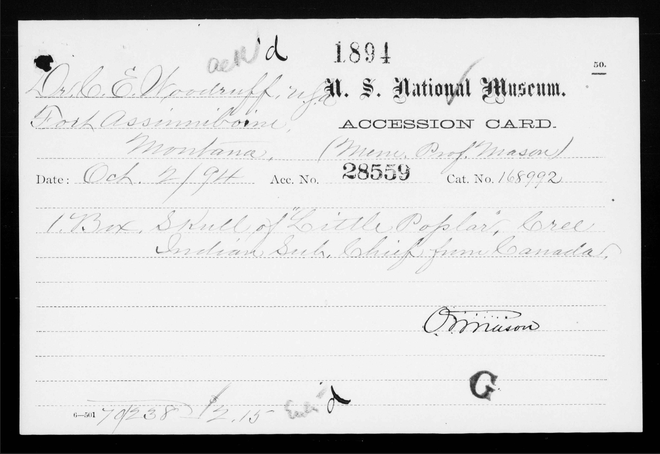

“1 Box. Skull of ‘Little Poplar,’ Cree Indian Sub Chief from Canada'' was written in faint but large, loopy cursive. It was a copy of an accession card, the document the Smithsonian filled out when receiving a donation of human remains. I scrutinized every inch of it. It looked like it had been sent from Fort Assiniboine, Montana, by Dr. C.E. Woodruff on October 2, 1894.

At that time, in the 1880s, our people travelled freely across what now is known as the U.S.-Canada border. They were there before the border was invented. Before colonization and the creation of “Canada” and the “United States,” Montana was just as much our homeland as Saskatchewan is now. When the Riel Rebellion broke out in Canada, some Plains Cree bands travelled south across the border to avoid persecution. Both of my great-great grandfathers did this, which is why I have some relatives on the Rocky Boy Reservation in Montana.

The facts sat like stones in my guts. I tossed and turned in the dark, thinking about how my great-great-grandfather’s skull was in the Smithsonian. How could my family member be in some institution’s box on a shelf? I felt sick. I regretted having opened up the email earlier that day. I shouldn’t have searched the database right before sleeping. I turned off my phone, closed my eyes.

But for a long time, I lay in bed, in a state of shock.

In an eerie coincidence, I had just started reading "Warrior Girl Unearthed" by Angeline Boulley. This novel is about the human remains of Indigenous people in American institutions. The protagonist, a young Anishinaabe woman named Perry Firekeeper-Birch, discovers that the local college has her ancestors in boxes and resolves to get them returned.

My mind turned to this book as I reflected on the parallels between the protagonist in the novel I was reading and my own life. Like Perry Firekeeper-Birch, I couldn't understand the depravity that would lead to storing my ancestor’s body parts in a museum. I felt violated somehow. How could something as personal as the remains of a loved one be treated with such disrespect?

‘All manner of deviltry’

The next day, I awoke with a ball of anxiety in my stomach. It was Christmas and my two kids were excited about their presents. But I found it challenging to be present and enjoy the morning. That night, I finally I responded to Mr. Tran’s email to let him know I had found an ancestor in the Post’s database.

“I have seen the documents that mention ‘Little Poplar' in accession file 028559,” he wrote, “and I have to warn you, the correspondence from the donor is quite horrifying.”

He was not wrong. The dehumanization of Indigenous people –– and so many others in the world –– is horrifying. I was grateful for Mr. Tran’s warning. He sent me the rest of the documents in the file, which meant I could skip the step of contacting the Smithsonian myself. Despite his warning, I was unprepared. Like someone recounting a trauma, I found myself laughing at the egregious wording of the letter. But it wasn’t actually funny—dissociation and deflection are common reactions to traumatic incidents.

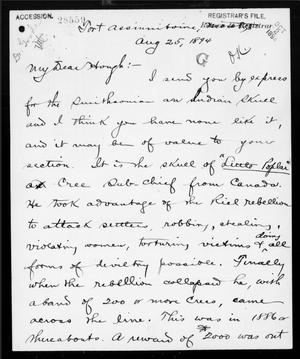

“I send you by express for the Smithsonian an Indian skull and I think you have none like it, and it may be of value to your section,” wrote the donor, Charles Woodruff, to the curator of the Smithsonian in 1894.

“It is the skull of Little Poplar,” he continues, “a Cree sub-chief from Canada. He took advantage of the Riel rebellion to attack settlers, robbing, stealing, violating women, torturing victims and doing all forms of deviltry.”

It was the “all manner of deviltry” bit that made me laugh out loud.

Coming from the pen of a man who had just dug up my great-great-grandfather’s grave, this seems almost like a compliment.

Woodruff’s letter said Little Polar had a bounty on his head of $2,000. “In Aug. 1886 he was murdered right here in this post by a half breed,” wrote Woodruff, referring to Fort Assiniboine, Montana, a U.S. military fort at the time.

He detailed how a soldier had “watched the grave for several years and when the flesh was all off he took the skull out and kept it as a relic.” He wrote how he went to the grave with the soldier to collect “a few odds and ends” from my great-great mosôm’s (grandather's) grave.

It was all too much. There was a bounty on his head? I never knew any of this history of my family. What an incredible story.

I knew I had to talk to my family, but I feared it would upset them. It turns out I needn’t have worried. When I asked my aunty, she was nonplussed.

“We knew he was in some museum somewhere,” she told me, “I also heard they have the clothes he was shot in.”

Hearing my aunty’s words reminded me of the knowledge we still hold in our families. We have an oral tradition, which is a legitimate form of knowledge-keeping. Our relatives have safeguarded the histories of our people for hundreds of years. I'm humbled when I consider the knowledge held by my family members. I’m so grateful they protected such important information about who I am — my lineage.

I have inherited more than intergenerational trauma. I have been given stories passed down from generation to generation for thousands of years. That’s why my aunty knows about our ancestors. That’s how I found out he was shot.-

I didn’t know these things as a child – I learned them later, as a teenager and adult, after reconnecting with my family on the Sweetgrass First Nation at the age of 14. Over the years, after spending time there visiting family, I had heard our family history the way it was meant to be told –– through oral transmission. I found it overwhelming that my ancestry was so well-regarded. Could I ever live up to that? I was just a short, poor, lost young woman who didn’t really know who she was or what she was doing in her life.

“We’re literally Indian princesses,” my cousin Irene said to me a few years ago. I laughed. I know she was being sarcastic, but I understand what she was referring to: the respected positions that my great-great-grandfathers held. It is an honor to be related to them. And, of course, the same applies to my great-grandmothers — who I know less about because of how archivists of the day favored men, leaving women out of many records. I wish I had the opportunity to learn about them as well.

Not just a right, but a responsibility

The next person I called was my dad. I was excited to tell him what I had learned and wanted his advice about whether I should visit to the Smithsonian. In some ways, I needed my family's permission to proceed because they were closer lineal descendants than I was. More importantly, they were my elders and knew more than I did.

“You see, Little Poplar was affiliated with Âyimisîs,” my dad told me on that call, “and Âyimisîs was the son of Big Bear. So, they were the northern branch of Treaty 6 Cree. And Âyimisîs was the head of the warrior society there, and Little Poplar was his cohort.”

I mentioned that I was considering contacting the Smithsonian about visiting the remains. I wondered aloud whether I had the right to do so.

“Oh, absolutely,” he said, “It’s not just a right, but a responsibility.”

I had never considered that visiting Little Poplar’s remains was my responsibility, but as soon as he spoke those words, I felt it. There is still so much for me to learn.“Those bones need ceremony,” he said, “and ceremony isn’t going to do itself.”

I shared the rest of Woodruff’s letter and asked, “Why would he take the soles of Little Poplar’s moccasins?”

Woodruff had mentioned that the soles of Little Poplar’s moccasins were one of the “odds and ends” he had taken from the grave.

“Well,” my dad said, “funeral moccasins would have had beaded soles.”

That made sense. Since the person won’t be walking on them, the soles could be decorated, too.

Long after his death, my ancestor continues to teach me about my culture.

A way to heal

I was nervous when I emailed the Smithsonian. Although I had been told by the reporters that lineal descendants receive the highest priority concerning human remains at the Smithsonian, I still felt like an imposter. I worried I wasn't in close enough relation. Was I really the appropriate person to make this request?

But it was me who was going to be close to Washington soon and could potentially visit. It was me The Washington Post had reached out to. I tried to let go of my doubts.

In the email, I explained who I was and my relationship with Little Poplar. I wrote of the obligation I had to bring medicines to this relative and to say prayers. I asked if I could have access to him.

I assumed the Smithsonian Institution would be a bureaucratic nightmare. I didn't know if they would respond or, if they did, how long it would take. The bureaucratic processes that came with colonization have been alienating to a lot of Indigenous people. We've had to get used to the fact that the words we speak are basically meaningless without a piece of paper to back it up — a paper that comes from the very government that destroyed our way of life in the first place.

The next morning, my phone rang. The name that flashed on my phone was Dorothy Lippert, the Smithsonian’s repatriation program manager.

My heart raced when I answered the call, but Ms. Lippert was gracious and kind. She seemed to be just as excited to be talking to me as I was to be talking to her. She told me the Smithsonian would accommodate my desire to visit. And more than that — they would pay for my transportation to D.C. and put me in a hotel while I was in Washington. After all of my agonizing, it was so simple and easy.

So, I will be heading to the Smithsonian on Monday.

I look forward to being a good relative and honoring my mosôm (grandfather). I give thanks to the grandmothers and grandfathers for putting me in this position as I set out on this sacred journey. I will bring him gifts of medicine, pray for him and give thanks for the gift he gave me –– my family. After all, those bones need ceremony, and ceremony isn’t going to do itself.

Eden Fineday is nehiyaw iskwew (Cree woman) from the Sweetgrass First Nation in Treaty 6 territory and the publisher of IndigiNews, one of few Indigenous-women-led journalism outlets globally. It is based in what is now known as Canada. A version of this story was published in IndigiNews.

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.